The report is

also available from the journal ‘Cryptologia’, vol13, no.3:

SECRET

HEADQUARTERS, ARMY SERVICE FORCES

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF SIGNAL OFFICER

WASHINGTON 25, D.C.

SPSIC-6

8

January 1945

MEMORANDUM

for Assistant. Chief of Staff, G-2

Subject:

Staff Study on OSS Cryptographic Plan

The enclosed

staff study is forwarded for your consideration and comment,

For the Chief

Signal Officer:

W, Preston Corderman

Colonel, Signal

Corps

Chiefs Signal Security Branch

1. Incl

Study on OSS

Cryptographic Plan

STAFF

STUDY ON OSS CRYPTOGRAPHIC PLAN

PROBLEM

PRESENTED

1. How may

the need of OSS for a high grade, high speed cryptographic system be satisfied?

FACTS BEARING

ON THE CASE

2. OSS has a

requirement for a high grade, high speed cryptographic system for the encipherment

and decipherment of secret traffic.

3. At the

present time OSS is using the Converter M-134-A (short title SIGMYC) to satisfy

this requirement.

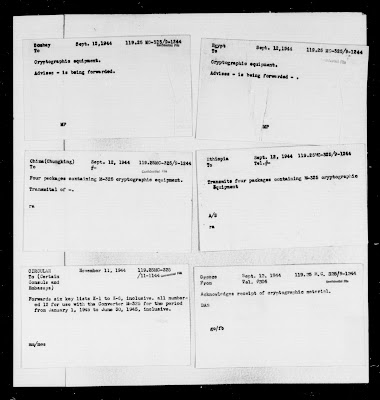

4. Prior to 5

April 1944, eight (8) SIGMYC were issued to OSS.

5. The

Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, authorized the issue of twenty-six (26) SIGMYC

to OSS by memorandum for Col. Corderman from Col. Clarke dated 5 April 1944, to

meet the expanding needs of that organization.

6. Since 5

April 1944, twenty-one (21) SIGMYC have been delivered to OSS. That

organization now holds twenty-nine (29) machines; five more are available for

issue.

7. In the

past OSS has used one universal set of rotors with SIGMYC. These rotors were

replaced once.

8. In

September 1944 OSS requested two new sets of rotors, one set to be used in

Europe and the other set in the Far East. Thirty-eight (38) sets of rotors

SIGRHAT (for use in the Far East) have been issued in compliance with that

request.

9.

Twenty-five (25) sets of rotors SIGSAAD (for use in Europe) have also been issued.

10.

Instructional documents associated with SIGMYC are "Operating Instructions

for Converter M-134 and M-134-A (Short title SIGKOC and ‘photographs and

Drawings of Converter M-134-A (short title SIGVYJ). No copies of these

publications are available for issue. This situation was caused by the

destruction of the instructional documents when Converters M-134-A were turned

in by Army holders.

11. Requests

are received for spare parts with each request for the issue of a SIGMYC. The

spare parts list always include rotor stepping solenoids. There are no rotor

stepping solenoids on hand in this agency. Three requests for these items have

not been fulfilled.

12. In accordance

with authorization of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, 27 July 1944, one

SIGTOT room circuit was furnished OSS in Washington. Authorization did not

extend to the issuance of tapes for use with this equipment. Additional SIGTOT

circuits have been made available to OSS in Europe. That organization is procuring

additional tape punching equipment to meet the increased demand for tape. OSS

requested the loan of such equipment until they are prepared to fulfill their own

needs for tape. This branch is supplying OSS with sufficient tape until that

organization is self-supporting in this respect.

13. Four (4) SIGCUM

have been issued to OSS with the approval of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2,

28 April 1944. These machines were sent to OSS in North Africa to replace four

(4) SlGCUM which were loaned to OSS by NATO and subsequently recalled by the

latter organization.

14. Within

the past six (6) months the communications requirements of OSS have markedly

increased. The cryptographic requirements have expanded proportionately. The

rapid expansion is vividly illustrated by the strip cipher requirements of that

organization. In June 1944 SSA requested OSS to furnish a monthly quota of

desired material in order to adjust production schedules here. The monthly

quota of strip cipher systems needed is now larger than the total number of

strip systems issued to OSS over a period of twenty (20) months.

15. It is

believed that the OSS will request the five (5) remaining SIGMYC of the authorized

allotment of twenty-six (26) machines. Instructional documents are not

available for issue with these converters. The reprinting of these documents

presents a major reproduction job.

16. OSS

encounters an ever present maintenance problem since the machines are

constantly breaking down. It is believed that the time is not far distant when

it will be impossible to maintain the machines adequately,

17. In order

to provide new rotors in the future it will be necessary to have rotors

returned from the field by OSS for rewiring. Thus, a rotation process will be

established to meet new demands for rotors which will result in the wearing out

of the rotors within a relatively short time. It is noted that it would take

between one to two years to procure new rotors.

18. OSS is

now trying out a modification of the standard --text deleted -- device, which utilizes -*- --text deleted--. That organization is contemplating an

increase in the distribution of these --text

deleted – to include the standard --text

deleted – held by OSS, thus, permitting inter-communication between the two

machines. The cryptographic principle involved his been approved by the Signal

Security Agency. OSS plans to utilize the -*-

--text deleted-- for secret radio transmissions.

19. The question arises as to what other means

are available. The following items of equipment are considered:

a. SIGTOT

This system

provides adequate security but the scarcity of equipment and the difficultly of

providing sufficient quantities of one-time tape render its use impracticable.

In addition SIGTOT is not at present adapted to multi-holders of a common

system, which is an operational requirement

b. SIGABA

Under present policy, it would be necessary to

assign a crypt team with each machine in order to make them available to OSS.

This presents a problem of securing sufficient personnel which appears

insurmountable at the present time. Furthermore, the use of SIGABA as a

solution to this problem is not generally regarded with favor.

c. SIGCUM

The

communications and cryptographic problems of OSS are developing rapidly in the Far

East where traffic is transmitted largely by radio. Since SIGCUM may not be

employed for secret traffic transmitted by means of radio the use of this

machine would not provide a solution to the problem, Although SIGCUM would be a

satisfactory substitute for SIGMYC in Europe, a revision of the cryptographic

facilities of OSS in that area is not considered feasible at this time.

d. SIGFOY

This

converter provides adequate security to fulfill the need for a high grade

cryptographic system and is well adapted to multiple holders of a common

system. Since it is not a high speed system, it would not fulfill this

requirement.

e. SIGLASE

This system

would provide adequate security and speed to meet the outlined requirements.

However, since SIGLASE is still in the development stage and the expected date

of issue is unknown it is not the immediate answer to the OSS problem.

20. From the

point of view of this branch the problem could be most acceptably solved by

making Army facilities available to OSS. It is realized that the latter organization

would probably not be favorably disposed toward such a solution,

CONCLUSIONS

21. The

continued use of SIGMYC by OSS in the Far East will present maintenance and

distribution problems which will be virtually impossible to solve.

22. A

replacement for SIGMYC is needed.

23. SIGABA,

SIGCUM and SIGTOT are not completely acceptable substitutes.

24. SIGFOY

and SIGLASE would be a solution to the problem but since it will require from

six to nine months to manufacture the SIGLASE, it cannot be considered an

immediate solution.

25. It

appears that the only immediate solution to the problem is for OSS traffic to

be handled by Army cryptographic facilities.

RECOMMENDATIONS

26. That OSS

be requested to utilize Army cryptographic communications facilities where such

exist.

27. That OSS

use its own cryptographic communications facilities where Army facilities do

not exist.

28. That, at

such time as the equipment referred to in paragraph 27 becomes unserviceable,

service be maintained by those Army cryptographic facilities and/or equipments

as may then be available.

A report dated 8

February 1946 (found in SRH-366

‘The history of Army strip cipher devices’) has more information on the

implementation of the aforementioned OSS cryptographic plan.