Their most

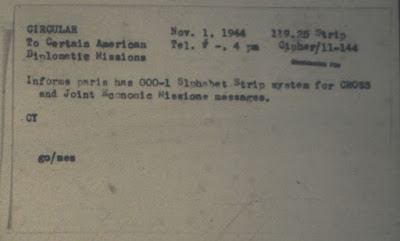

modern and (in theory) secure system was the M-138-A

strip cipher. Unfortunately for the Americans this system

was compromised and diplomatic messages were read by the Germans, Finns,

Japanese, Italians and Hungarians. The strip

cipher carried the most important diplomatic traffic of the United States

(at least until mid/late 1944) and by reading these messages the Axis powers

gained insights into global US policy.

Germans,

Finns and Japanese cooperated on the solution of the strip cipher. In 1941

the Japanese gave to the Germans alphabet strips and numerical keys that they

had copied from a US consulate in 1939 and these were passed on by the Germans

to their Finnish allies in 1942. Then in 1943 the Finns started sharing their

results with Japan.

Finnish

solution of State Department cryptosystems

During WWII

the Finnish

signal intelligence service worked mostly on Soviet military and NKVD

cryptosystems however they did have a small diplomatic section located in Mikkeli. This department had

about 38 analysts, with the majority working on US codes.

Head of the

department was Mary Grashorn. Other important people were Pentti Aalto

(effective head of the US section) and the experts on the M-138 strip

cipher Karl

Erik Henriksson and Kalevi Loimaranta.

Their main

wartime success was the solution of the State Department’s M-138-A cipher. The

solution of this high level system gave them access to important diplomatic

messages from US embassies in Europe and around the world.

Apart from

purely diplomatic traffic they were also able to read messages of other US

agencies that used State department cryptosystems, such as the OSS

-Office of Strategic Services Bern station, Military

Attaché in Switzerland, Office

of War Information representative in Switzerland, the

Foreign Economic Administration, War Shipping Administration, Office of

Lend-Lease Administration and the War Refugee Board.

Operation

Stella Polaris

In September

1944 Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. The people in charge of

the Finnish signal intelligence service anticipated this move and fearing a

Soviet takeover of the country had taken measures to relocate the radio service

to Sweden. This operation was called Stella Polaris (Polar Star).

In late

September roughly 700 people, comprising members of the intelligence services

and their families were transported by ship to Sweden. The Finns had come to an

agreement with the Swedish intelligence service that their people would be

allowed to stay and in return the Swedes would get the Finnish crypto archives

and their radio equipment. At the same time colonel Hallamaa, head of the

signals intelligence service, gathered funds for the Stella Polaris group by

selling the solved codes in the Finnish archives to the Americans, British and

Japanese.

The Stella

Polaris operation was dependent on secrecy. However the open market for Soviet

codes made the Swedish government uneasy. In the end most of the Finnish

personnel chose to return to Finland, since the feared Soviet takeover did not

materialize.

The Higgs

memorandum

In September

1944 colonel Hallamaa met

with L. Randolph Higgs, an official of the US embassy in Sweden and told him

about their successes with US diplomatic codes and ciphers.

This

information was summarized in a report prepared by Higgs, dated 30 September

1944.

The report

can be found in the US National Archives - collection RG 84 ‘Records of the

Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State’ - ‘US Legation/Embassy

Stockholm, Sweden’ - ‘Top Secret General Records File: 1944’.

Higgs met

with colonel Hallamaa on September 29 and the OSS officials Tikander and Cole

were also present during their discussion.

Hallamaa

stated that he was an administrator, not a cryptanalyst and about 10-12 of his men

worked on US diplomatic codes.

His unit had

solved the US codes Gray, Brown, M-138-A strip cipher and enciphered codebooks

(probably the A1, B1, C1).

The high

level M-138-A system had been solved mostly by taking advantage of operator

mistakes such as sending strip cipher information on other systems that had already

been broken or sending the same message in different strips one of which had

been broken.

The strip

cipher was considered a strong encryption system and had been adopted by the

Finns for some of their traffic.

Important

diplomatic messages from the US embassies in Switzerland, Sweden and Finland

were read by the Finnish codebreakers.

Regarding Bern, Switzerland most of the

messages dealt with intelligence matters:

‘Replying to my request for information

regarding the contents of the messages from our Legation in Bern to the

Department, Col. Hallamaa said the great bulk of them were intelligence

messages dealing with conditions in Germany, France, Italy and the Balkans. He

spoke in complimentary terms about ‘Harrison’s’ information service’.

Regarding

Helsinki, Finland Hallamaa stated that thanks to the decoded diplomatic traffic

they were always informed of current US policy initiatives:

‘Col. Hallamaa said that they always knew

before McClintock arrived at the Foreign Office what he was coming to talk about’.

Hallamaa

revealed a lot of confidential information to the Americans and volunteered to

have some of his experts interviewed.

The interview was conducted on friendly

terms with Higgs stating; ‘Col. Hallamaa

was most pleasant and seemed to be entirely frank and open regarding the

matters discussed’.

Additional

information: In

November 1944 the US cryptanalysts Paavo Carlson of the Army’s Signal

Security Agency and Paul E. Goldsberry of the State

Department’s cipher unit interviewed Finnish officials regarding their work

on US codes. Their report can be found here.