During WWII Japan’s

Foreign Ministry used several cryptologic systems in order to protect its

diplomatic communications from eavesdroppers. In 1939 the PURPLE cipher

machine was introduced for the most important embassies, however not

all stations had this equipment so hand ciphers continued to play an important

role in the prewar period and during the war.

The main hand

systems were transposed codes.

Historical

overview

The first

Japanese diplomatic system identified by US codebreakers was introduced during

WWI and it was a simple bigram code called ‘JA’. There were two code tables,

one of vowel-consonant combinations and the other of consonant-vowel. Similar

systems, some with 4-letter code tables were introduced in the 1920’s.

These

unenciphered codes were easy to solve simply by taking advantage of the

repetitions of the codegroups of the most commonly used words and phrases. US

codebreakers solved these codes and thus learned details of Japan’s foreign

policy. During the Washington

Naval Conference the codebreakers of Herbert Yardley’s Black Chamber were

able to solve the Japanese code and their success allowed the US diplomats to

pressure the Japanese representatives to agree to a battleship ratio of 5-5-3

for USA-UK-Japan. However this success became public knowledge when in

1931 Yardley published ‘The

American Black Chamber’, a summary of the codebreaking achievements of his

group. The book became an international best seller and especially in Japan it

led to the introduction of new, more secure cryptosystems.

In the 1930’s

the Japanese Foreign Ministry upgraded the security of its communications by

introducing the RED and PURPLE cipher machines and by enciphering their codes mainly with

transposition systems.

Japanese

transposed codes J-16 to J-19

The J-19 code

had bigram and 4- letter code tables similar to the ones used previously by the

Japanese Foreign Ministry. According to the NSA study ‘West Wind Clear:

Cryptology and the Winds Message Controversy A Documentary History’ it was

used from 21 June 1941 till 15 August 1943.

In terms of

security the J-19 FUJI and the similar codes J-16 MATSU to J-18 SAKURA, that

preceded it in the period 1940-41, were much more sophisticated than the older

Japanese diplomatic systems. They had roughly double the number of code groups

at ~1.600, these included 676 bigram entries and in addition there was a 4-letter table with 900

entries for ‘common foreign words, usually of a technical nature, proper

names, geographic locations, months of the year, etc’.

These codes

were enciphered mainly by columnar transposition based on a numerical key, with

a stencil being used for additional security. The presence of ‘blank’ cages in

the box created irregular lengths for each column of the text.

Examples of

the stencils and numerical keys from ‘West Wind Clear’:

The

replacements of J-19 FUJI

In summer ’43

J-19 FUJI was replaced by three new systems. The transposed codes TOKI and GEAM

and the enciphered code ‘Cypher Book No1’.

TOKI was used

in the period 1943-45 and it was similar to J-19 in that it was a code

transposed on a stencil. The TOKI system was used by Japan’s embassies and

consulates in Europe (2).

Just like its

predecessor it was solved by the Anglo-Americans and the German codebreakers.

Allied exploitation

of the TOKI cipher

The US

effort

The TOKI

transposed code was different from its predecessor J-19 FUJI in that it was

used by European posts, while J-19 was used by Japanese diplomatic missions from

around the world. Also TOKI was made up of 2 and 3 letter code groups while

J-19 had 2 and 4 letter groups. The code groups were arranged in a non

systematic manner thus making solution more difficult (3).

Examples of

recovered code values (4):

The TOKI

messages were enciphered using stencils and transposition keys that changed

within the same message. Specifically the indicator of the message designated 3

stencils and 3 numerical keys to be used in encipherment. Each table had 250

blocks (25x10) but 50 were crossed out according to a specific system, thus 200

letters could be enciphered. If the message was longer than that then the next

stencil and numerical key designated by the indicator was used.

Initially the

date of the message and the signature of the originator were used to select null

and blank blocks (5). In December 1943 this procedure was changed. Null blocks

were abolished and the new procedure for crossing out blocks was the following

(6):

‘at the intersection of the column and row;

five blanks are inserted; the odd blanks are inserted vertically, the even

blanks horizontally, for numbers 1-10 in numerical order. Blanks to be inserted

below row 10 are continued at row 1. If a blank is already present in a space

to be used for another blank, it is skipped over; always five blanks are

inserted for each intersection point, so that the total number of blanks is 50,

and the number of letters in the matrix is 200. Three such matrices and three

such random sequences are used for each indicator, if the length of the message

warrants this. If a message is longer than 600 textual letters, the first

sequence is used for a fourth block, the second for a fifth block, etc..’

Examples of

stencils and transposition keys (7):

The use of a

2 and 3 letter code together with different stencils and transposition keys

made solution difficult. The main method used was to analyze a large number of

messages ‘in depth’ (enciphered with the same settings, identified by having

the same indicator), then it was possible to use anagramming in order to solve

the encipherment and recover the code values.

The report

SRH-361 ‘History of the Signal Security Agency Volume Two The General

Cryptanalytic Problems’, p283 says about TOKI/JBA:

JBA, a transposition system of a

degree of security second only to the Purple machine-cipher system (JAA), was

solved by statistical methods within six weeks. This solution is believed to be

the first instance of the recovery of an unknown transposition of an unknown

code by purely statistical means. Beginning groups, and later, code groups

within the body of the text were found by matching stretches of cipher text

from several messages with the same indicator. Frequent digraphs were recorded,

and eventually the transposition patterns and tetragraphic code groups were

recovered despite the presence of occasional trigraphic groups, the use of

blanks in the matrix, and the use of the letters of the signature as nulls

throughout the message.

Apart from statistical methods it

was possible to solve messages by taking advantage of operator mistakes such as

sending the same message in two different keys, enciphering the same message on

TOKI and GEAM ciphers, having stereotyped beginnings etc

The

Gee-Whizzer

During the

war traffic on the J-series codes increased significantly and the solution of

the daily changing settings became a problem for the small number of people

working on Japanese systems, so there was an effort to automate the process.

The device built was an attachment for standard IBM punch card equipment called

the ‘Electromechanagrammer’ or ‘Gee-Whizzer’.

According to

the NSA study ‘It Wasn’t All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate

Cryptanalysis, 1930s – 1960s’, p50-51:

‘The Gee

Whizzer had been the first to arrive. In its initial version it did not look

impressive; it was just a box containing relays and telephone system type

rotary switches. But when it was wired to one of the tabulating machines, it

caused amazement and pride. Although primitive and ugly, it worked and saved

hundreds of hours of dreadful labor needed to penetrate an important diplomatic

target. It proved so useful that a series of larger and more sophisticated

"Whizzers" was constructed during the war……………….When the Japanese

made one of their diplomatic "transposition" systems much more

difficult to solve through hand anagramming (reshuffling columns of code until

they made "sense"), the American army did not have the manpower

needed to apply the traditional hand tests.

Friedman's

response was to try to find a way to further automate what had become a

standard approach to mechanically testing for meaningful

decipherments……………………………………..Rosen and the IBM consultants realized that not

much could be done about the cards; there was no other viable memory medium.

But it was thought that it might be possible to eliminate all but significant

results from being printed. Rosen and his men, with the permission and help of

IBM, turned the idea into the first and very simple Gee Whizzer. The Whizzer's

two six-point, twenty-five-position rotary switches signalled the tabulator

when the old log values that were not approaching a criterion value should be

dropped from its counters. Then they instructed the tabulator to start building

up a new plain-language indicator value.

Simple,

inexpensive, and quickly implemented, the Gee Whizzer reinforced the belief

among the cryptoengineers in Washington that practical and evolutionary changes

were the ones that should be given support.’

Importance of the TOKI system

From the

available statistics on the solved TOKI messages and the reports issued it is

clear that it was one of the high level Japanese diplomatic hand systems

(together with JBB/GEAM and JBC/Cypher Book No1) (8).

In the period

1943-45 the main Japanese diplomatic systems decoded and forwarded to the

Military Intelligence Service were the Purple cipher

machine (JAA), the ciphers TOKI (JBA), GEAM (JBB), Cypher Book No1 (JBC)

and the unenciphered code LA (JAH).

The

Australian effort

In Australia

the Diplomatic Special Section (D

Special Section) of the Australian Military Forces HQ in Melbourne decrypted

Japanese diplomatic ciphers. This unit was headed in the period 1942-44 by A.D.

Trendall, Professor of Greek at Sydney University. Despite the small size of

the unit considerable success was achieved in the solution of Japanese

communications (9).

According to

the report ‘Special Intelligence Section report - Japanese Diplomatic

ciphers’ (10) the TOKI cipher was the first of the new Japanese

Foreign Office ciphers to be broken.

The system

was quickly compromised by the Japanese Ambassador in Lisbon Morishima Morito.

The report says that he committed a fatal mistake by sending the same message

in two different keys. This allowed the two messages to be solved and a few

code groups to be identified.

More

codegroups were recovered when some messages were sent both in the TOKI and GEAM

ciphers. Since GEAM (JBB) was easier to solve it was then possible to identify

the equivalent groups in solved TOKI (JBA) messages. When the cipher was

modified in December 1943 it was possible to break in again by solving two

messages sent in the same key.

Regarding the

content of the messages the report says:

‘BA was used only to a moderate extent and

the material it contained was of varying interest ranging from general Tokyo

circulars upon international happenings to dull routine matters about couriers.

Most BA messages from Russia were on the subject of couriers, visas and

rations. However Stockholm was in the habit of sending all his chōhōsha (spy reports) in BA and much

information was obtained therefrom. Although the second system of BA cypher

might well have proved unbreakable the Foreign Ministry did not regard it very

highly and issued instructions that it was to be used only for routine matters;

more confidential material was to be sent in the recyphering tables. This was

satisfactory from our point of view as we encountered far more difficulty in

breaking and reading the second BA system than we did in recovering recyphering

tables’.

The German

effort

Foreign

diplomatic codes and ciphers were worked on by three different German agencies,

the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, the

Foreign Ministry’s deciphering department Pers Z and the Air

Ministry’s Research Department - Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt.

OKW/Chi

effort

At the High

Command’s deciphering department - OKW/Chi, Japanese diplomatic systems were

worked on by a subsection of Referat 13, headed by 1st Lieutenant dr Adler.

About 15 people were employed by the unit (11) and according to Reinhard Wagner

(a member of the section) the TOKI cipher was solved by the department.

Wagner said

in his postwar interrogation report (12):

(3) A transposition procedure

(Wuerfelverfahren), on which WAGNER did not work himself and which he knew only

through having translated messages passed in the system. He could say of this

system only that there was a daily changing keyword, and the reciphering

process was complicated by Raster. The system remained valid until August 1943.

(4) The successor to the above

transposition procedure, which WAGNER helped to solve, employed a basic 2 and 4

letter code book. Transposition was done in a width of 25 and a depth of 10.

The keyword was changed arbitrarily. Not all the fields in the transposition

square were employed but gaps (Loecher) were left. For example, the first

square in the first column was to be left blank, the second square down in the

second column, and so forth up to ten. In the eleventh column the top five

squares down might be left blank, and in the twenty-first column the bottom

five squares. In January 1944 the procedure was complicated by causing blank

squares to be left vertically and horizontally. E.g., in column one, starting

from the top down five squares were to be left blank. In column two, starting

with the second. square down, five squares horizontally were to be left blank. In

column three, starting with the third square down, five squares vertically were

to be left blank, etc. The referat was successful in breaking this system.

At OKW/Chi

they not only solved the Japanese transposed codes but also built a specialized

cryptanalytic device called the ‘Bigram search device’ (bigramm suchgerät) for

recovering the daily settings. EASI vol3, p65 says:

‘FUJI, a

transposition by means of a transposition square with nulls applied to a two

and four letter code. This system was read until it ended in August, 1943. It

was broken in a very short time by the use of special apparatus designed by the

research section and operated by Weber. New traffic could be read in less than

two hours with the aid of this machine.’

The ‘Bigram

search device’ is called ‘digraph weight recorder’ in the US report ‘European

Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ volume 2. In pages 51-53 details are

given on the operation of this device:

‘The

digraph "weight" recorder consisted of: two teleprinter tape reading

heads, a relay-bank interpreter circuit, a plugboard ‘’weight’’ assignor and a

recording pen and drum.

Each head

read its tape photoelectrically, at a speed of 75 positions per second.’

The machine

could find a solution in less than two hours and did the work of 20 people,

thus saving manpower.

Pers Z

effort

At the

Foreign Ministry’s deciphering department Pers Z Japanese systems were

worked on by a group headed by Senior Specialist dr Rudolf Schauffler. This

section successfully solved the Japanese diplomatic transposed codes, including

the TOKI cipher which in Pers Z reports was designated as JB-64.

Dr Schroeter,

a cryptanalyst of the mathematical research section who worked on Japanese

ciphers, said in TICOM

report I-22, p17

136. Dr. Schroeter: Had joined the

organization comparatively later (Spring 1941) and had no intention of ‘staying

on'. He was a lecturer in mathematical logic at the University of Münster.

He had joined Dr. Kunze’s party and worked independently on Japanese

recypherments.

137. He started work on simple

transposition recypherments of codes; they were single transpositions with

nulls over two-letter books. In the autumn of 1942-43 he worked on a Japanese

'Greater East Asia‘ traffic consisting of single transposition over a

two-letter book systematically constructed, groups consisting of cv. The cage

was 6 letters long and 5 or 10 letters deep with blanks evenly distributed

throughout; there were three keys.

138. The system used with European

posts consisted of transposition with a 25 place stencil. The stencil changed

sometimes as often as three times within the message. The blanks in the stencil

were filled out with the originator's signature, e.g. SHIGEMITSU. The basic

book was more difficult and employed groups of two or three letters. The system

was broken largely-owing to a twelve part message from Moscow with similar

beginnings to each part. This system, known as 'JB 64’, is still current,

though the stencil changes more frequently. Dr. Olbricht used to work on it.

Dr. Schroeter sketched a specimen stencil.

It is

interesting to note that a cryptanalytic device called ‘Spezialvergleicher’ was used to solve the Japanese transposed codes

(13).

In the TICOM

collection of the German Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive there are several

folders containing worksheets of solved JB-64 messages for the period 1943-45 (14).

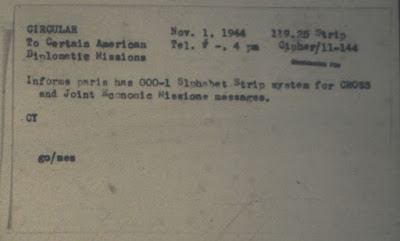

For example (15):

Forschungsamt

effort

At the Air

Ministry’s Research Department Japanese systems were worked on by Abteilung 7 (USA, UK, Ireland, South America, Spain,

Portugal, Turkey, Egypt, Far East). The department had about 60-70 workers.

Unfortunately

at this time there is limited information on the Forschungsamt cryptanalytic

effort. In TICOM

report I-25, p7 dr Martin Paetzel (deputy director of Main Department IV -

Decipherment) said that a Japanese transposed code was worked on in the middle

of 1943 but it was not read currently. It is possible that he was referring to

TOKI.

Messages

from the Japanese embassy in the Soviet Union

The Germans

were particularly interested in the communications of the Japanese diplomats in

the Soviet Union. It seems that this embassy was either not given a PURPLE

machine or perhaps they had to dismantle it in 1941, so they relied on hand

ciphers for their most important messages.

During WWII

Japan fought on the side of the Axis but was careful to avoid a confrontation

with the Soviet Union. War between the SU and Japan finally broke out in August

1945 but during the period 1941-45 Japanese diplomats were free to collect and

transmit important information from the SU on military and political

developments as well as their discussions and negotiations with Soviet

officials. These messages were a prime target for the Allied and German

codebreakers.

In the period

1943-45 the messages of the Japanese ambassador clearly showed the deterioration

of Soviet-Japanese relations. Some of these messages were used in a series of reports

prepared by Giselher Wirsing, an

accomplished author and journalist, who in 1944 joined the Sicherheitsdienst foreign

intelligence department as an evaluator.

Wirsing had come to the attention of General Schellenberg (head of SD

foreign intelligence) due to his clear headed analysis of the global political

situation and of Germany’s poor outlook for the future. Under Schellenberg’s

protection he wrote a series of objective reports (called Egmont

berichte) showing that Germany was losing the war and thus a political

solution would have to be found to avoid total defeat (16).

In his

postwar interrogations Wirsing mentioned the decoded messages of the Moscow

embassy that he used in his reports:

‘Japanese ambassador in Moscow to his

Government. Occasional telegrams were deciphered which indicated clearly that

the Japanese were having increasing difficulties in maintaining friendly

relations with the USSR. Through this source came confirmation from an Amt VI

Far East V-man regarding a secret meeting of Japanese and Russian emissaries

somewhere in SIBERIA’.

‘When STALIN delivered his famous address on 7 November 1944,

singling JAPAN out as an aggressor nation, WIRSING, in a special report written

at the request of SCHELLENBERG, read into this sentence the accomplished fact

of a fundamental change of Russian policy towards JAPAN. Again SCHELLENBERG

demurred. Then, approximately three weeks later, a report by ambassador SATO to

his government was intercepted in which he related a conversation he had had

with MOLOTOV in connection with a Japanese note expressing concern over

anti-Japanese utterances by a Russian colonel in a public address. MOLOTOV, according

to SATO, availed himself of this opportunity to advise the Japanese Government

not to mistake rhetorical exuberance for an expression of the considered policy

of the Kremlin. However, MOLOTOV added, the time would come when certain outstanding

questions of a more fundamental nature would have to be thrashed out between

the two nations.‘

It is

reasonable to assume that some of these messages were enciphered with the TOKI

system.

Notes:

(2). TICOM

report I-22, p17 and US report ‘The solution of the Japanese transposed

code JBA’, p1 (NARA - RG 457 - Entry 9032

– NR 2828)

(3). US

report ‘The solution of the Japanese transposed code JBA’ (NARA - RG 457 - Entry 9032 – NR 2828)

(4). US

report ‘Master JBA trigraph charts‘ (NARA

- RG 457 - Entry 9032 – NR 2458)

(5). The

procedure as described in ‘The solution of the Japanese transposed code JBA’

was as follows. The cipher clerk would take the stencil, write the numerical

key at the top and then add the letters of the signature of the originator (for

example SATOAMBASS) at the blocks on row 1-column 1, row 2-column 2, row

3-column 3 etc.

The blank

blocks were selected from a key table which identified the columns to be

crossed out for each day of the month.

(6). US

report ‘The solution of the Japanese transposed code JBA’ (NARA - RG 457 - Entry 9032 – NR 2828)

(7). US

reports ‘Report on Japanese diplomatic systems 1944’ (NARA - RG 457 - Entry 9032 – NR 3095) and ‘The solution of the

Japanese transposed code JBA’ (NARA - RG

457 - Entry 9032 – NR 2828)

(8). US

report 'Foreign Cryptographic Systems, 1942-1945' (NARA - RG 457 - Entry 9032 - NR3254)

(9). Breaking

Japanese Diplomatic Codes David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second

World War, chapter 1

(10). Australian

National Archives - NAA: A6923, 1/REFERENCE COPY - (barcode 12127133)

(12). TICOM I-90

‘Interrogation of Herr Reinhard Wagner (OKW/Chi) on Japanese systems’, p3

(13). TICOM

I-22, p18

(14). German

Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive - TICOM collection - files Nr. 2.465-2.471

(15). German

Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive - TICOM collection - file Nr. 2.471 - Japan 1944/45 ‘JB64, 1481-1644’, Diplom. Briefverkehr

(16). British

national archives KV 2/140

‘Giselher WIRSING: Journalist and author’

Sources:

‘European

Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ volumes 2,3,6,7 , TICOM reports I-22,

I-25, I-90, I-124, I-150, DF-187B , ‘The Codebreakers’, ‘Breaking

Japanese Diplomatic Codes David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second

World War’, United States Cryptologic History Series IV: World War II

Volume X: ‘West

Wind Clear: Cryptology and the Winds Message Controversy A Documentary History’,

United States Cryptologic History, Special Series, Volume 6, ‘It

Wasn’t All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s – 1960s’,

NSA interviews of Frank Rowlett 1974 (National Cryptologic Museum Library), Australian

National archives: ‘Special Intelligence Section report - Japanese Diplomatic

ciphers’, NARA reports: ‘The solution of the Japanese transposed code JBA’, 'Foreign

Cryptographic Systems, 1942-1945', ‘Report on Japanese diplomatic systems 1944’,

‘Master JBA trigraph charts‘, NSA report SRH-361 ‘History

of the Signal Security Agency Volume Two The General Cryptanalytic Problems’

Acknowledgements: I have to thank Rene Stein for

identifying several of the NARA JBA reports.