The use of secret intelligence and codebreaking during WWII, by both the Allies and Axis, is a fascinating subject. For the German side some of their greatest successes were achieved by the Navy’s signal intelligence agency B-Dienst (Beobachtungsdienst).

In the field of naval codes this organization was able to read the principal Royal Navy cryptosystems from 1938 to end of 1943. The advantages of reading this traffic were of immense importance for the German side.

In 1940 decoded British naval messages alerted the Germans to the movement of troops to Norway and allowed them to preempt the Allied plan.

During the Battle of the Atlantic most of the intelligence supplied to the U-boats came from codebreaking.

Admiral Doenitz considered it the best source of Naval intelligence and often the only source of operational information.

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest campaign of WWII and it involved the German navy’s U-boat command versus Allied commercial shipping and the surface forces of the British, Canadian and US navies which escorted them.

The German strategy was to exploit Britain’s lack of self sufficiency in raw materials and agricultural products. If they managed to sink the majority of supplies crossing the Atlantic then Britain would be economically strangled and would have no choice but to sue for peace. Even if this did not happen the lack of military supplies would make it impossible to launch heavy attacks on continental Europe.

The head of the U-boat service, Admiral Doenitz knew he needed large numbers of submarines in order to achieve victory. His operational strategy was to overwhelm convoys with a large number of U-boats. These wolfpacks could evade the few escort vessels and sink the majority of commercial ships. The rest would disperse and could be picked off at a later time.

In order for the wolfpack strategy to work the Germans needed to know the route and speed of the convoys in advance. Their main ways of gaining this information was through aerial reconnaissance and signals intelligence.

According to post war reports D/F (direction finding) was not very helpful in locating the convoys.

Aerial reconnaissance was the job of the Luftwaffe and was hampered by the lack of a long range bomber aircraft that could search the Atlantic. The planes that the Germans used in that role were the Focke Wulf 200,the Heinkel 177 and the Junkers 290. The Fw 200 was a modified commercial airliner and its structure could not absorb all the weight of weaponry and equipment. So accident were frequent. More important however was the fact that at any given time only a handful were available for naval recon operations. The Ju 290 was also used in tiny numbers and the He 177 had many development problems that delayed its operational use.

In the end naval reconnaissance was never an important mission for the Luftwaffe and few resources were invested in it.

This left only codebreaking. Thankfully the naval codebreakers were able to solve the Royal Navy’s systems, both the high level Cypher and Code plus the Merchant Ships code.

The central cryptanalytic department OKM/SKL IV/III (Oberkommando der Marine/Seekriegsleitung IV/III) was based in Berlin and had roughly 1,000 people working on foreign codes. Around 800 were assigned to the British section. This was quite an investment in terms of manpower! Still the results justified the expenditure. From summer 1942 they were also aided in their efforts by IBM /Hollerith punch card equipment.

In order to access the successes of the B-Dienst it is imperative that we understand the cryptologic systems used by the Royal Navy in WWII.

At the start of the war the main systems were:

1. Naval Cypher No1, a 4-figure book used since 1934.

2. Administrative Code, a 5-figure book used since 1934.

3. Auxiliary Code No3, a 4-letter book used since 1937 by small units.

Merchant ships used their own codebook. During 1939 this was the International Code and Naval Appendix. From January ’40 to April ’42 it was the Merchant Navy Code and for the rest of the war the Merchant Ships Code.

All these codes and cyphers were reciphered with special tables. There were different sets of tables depending on the geographic area and the level of traffic (Commander in Chief table, Flag Officer’s tables, General table etc).

The reciphering tables were changed at frequent intervals.

These security measures did not stop the Germans from ‘breaking’ the naval codes. They were greatly aided in their efforts by the poor British decision to use the Administrative and Auxiliary codes unreciphered for non-confidential traffic. This allowed them to recover the true values of the codebooks and then focus only on breaking the enciphering tables.

In 1935-6 the Administrative Code was solved and in 1938 the Naval Cypher followed. At the start of the war the Auxiliary Code was also read with little difficulty.

By the spring of 1940 the work of the B-Dienst had progressed so far that they were able to read virtually everything of importance in connection with the Norway operation. For example their success rate was 30-50% of intercepted cypher traffic.

There is no doubt that the German victory in Norway owed a great deal to the efforts of the B-Dienst.

British cipher security was upgraded on 20 August 1940 when new editions of the Cypher and Code were introduced. The Auxiliary Code was discontinued and instead small units used the Naval Code enciphered with Auxiliary Vessels tables.

These changes hindered the German effort but could not defeat it. The German naval codebreakers, after hard work, managed to ‘break’ in back into these systems.

However from June 1941 their main effort was directed at the new Naval Cypher No3 used in the Atlantic by the British, American and Canadian navies.

This was a 4-figure book originally created for the Royal Navy but since no other system had been prepared for inter-allied naval traffic it was shared with the US navy and the Canadians. The Germans called it ‘Frankfurt’.

The subtractor tables used with Cypher No3 had 15,000 groups. Since traffic was much heavier than anticipated (M table-General: 218,000 groups in August ’42, S table-Atlantic: 148,000 groups in October 1942 and 220,000 in November), code-groups were reused several times and the Germans used these ‘depths’ to reconstruct the tables. The British tried to limit ‘depths’ by introducing new tables. Originally these were changed every month but from September ‘42 every 15 days and in ‘43 every 10 days.

Naval Cypher No3 was introduced in June ’41. The Germans were able to ‘break’ into the traffic in December ’41. By February ’42 they had reconstructed the book and till 15 December ’42 they were reading a large proportion of the traffic (at times up to 80% of intercepted messages). In December an indicator change set them back but from February ’43 they were again able to read the messages.

Their greatest success with the convoy cypher was achieved in 1943. From February till June they often read signals 10-20 hours in advance of the actions mentioned in them. Also from February ‘42 to June ‘43 they could decode the daily Admiralty U-boat disposition signal nearly every day.

In the Atlantic they also exploited the Naval Code and the merchant ship codes.

Naval Code versions 1-3 (valid from August ’40 to January ’44) were read by the B-Dienst and some of the messages from the Atlantic and Western approaches areas were decoded.

The Merchant Navy code and the Merchant ships code were captured from commercial ships. Their enciphering tables were solved throughout the war. The official history ‘British intelligence in the Second World War’ says that these two systems ‘were a prolific source of information to the B-Dienst second only to the Naval Cypher No3 in their importance to the battle of the Atlantic’.

Taken together, these successes meant that from the start of the war till the summer of 1943 the German High Command had the upper hand in the field of intelligence. Thus Doenitz could place his U-boat groups at the time and place where they would do the most damage.

German fortunes declined after summer ’43. In June ’43 Naval Cypher No5 replaced No3 in the Atlantic. It was recyphered by a new system called the ‘Stencil Subtractor’. In November the Combined Cipher Machine was also used by Allied warships in the Atlantic. In December the Auxiliary vessels tables transferred to the Stencil system. During the same month the Merchant Ships code was used with enciphered coordinates.

By January 1944 the Germans had lost all their high level sources of information. They did not give up though. They assigned a large staff to research the new stencil system and managed to ‘break’ the Auxiliary Vessels traffic of December ’43 in early ’44. They were able to do so because they had already reconstructed the Naval Code No3 which was used at the time. This was changed in January with Naval Code No4.

Their conclusion was that without having the new Naval Code and Cypher books they could not hope to solve the traffic. If however they managed to get hold of the codebooks then solution would not be hard. Unfortunately for them they did not manage to get their hands on the Royal navy’s codebooks. Their only remaining successes would be with low level codes.

These cryptologic changes were not by accident. The Brits suspected that their codes were not secure but they got definitive proof only when they started ‘breaking’ the Enigma again in 1943. For various reasons it took them quite a long time to upgrade their security but once they did B-Dienst was effectively defeated.

Since I’ve covered the main achievements of the German side it’s important to also go through the British operations.

The other side of the hill:

Doenitz needed to be kept informed of the operations of his submarines at all times. This meant that the U-boats sent daily reports of their sightings, route and fuel situation. The U-boat command also sent its orders daily.

In order to protect this traffic the Germans enciphered it with the naval Enigma M3 and from February 1942 the 4-rotor M4.

The M3 Enigma used by the German navy had additional security measures compared to the standard Wehrmacht Enigma. Apart from the 5 rotors, used by all services, it had an additional 3 that were used only by the navy. These had two notches (compared to one for the standard ones) making movement more irregular.

The M4 had one more (non moving) rotor position that was used with two additional rotors. These however could not be used in the other three positions. Cryptographically the M4 was much more secure than the 3-rotor Enigma and its use caused a crisis in the Anglo-American agencies.

Signaling procedures were also much stricter than those of the other services. For example indicators were not selected by the operator but from a book (Kennbuch) and they were enciphered with a bigram table. Both Kennbuch and bigram tables were changed several times during the war thus complicating the work of Hut 8.

Coordinates were taken from a grid table. From June ’41 coordinates were further disguised by using fixed reference points on the grid table. From November ’41 an Adressbuch was used to encipher the grid references.

These security precautions on behalf of the Navy meant that their Enigma traffic was much harder to decode that the Airforce version which was read regularly.

The section of Bletchley Park that attacked naval Enigma traffic was Hut 8 headed, in the beginning, by the mathematician Alan Turing. During the period 1939-41 they did extensive research on the indicator system and the naval Enigma. They were aided by the capture of the 3 extra rotors. Two from U-33 in February 1940 and the last one in August 1940.

Despite the excellent work done in studying the naval Enigma and the indicator system, by March ’41 their only operational success had been the solution of the Enigma ‘key’ for 5 days of 1938 and 6 days in April 1940.

Obviously something had to be done to force this deadlock! This ‘something’ would be a commando operation against the German forces in the Norwegian Lofoten islands. The goal was to capture cipher material that could be used by Hut 8. The operation took place on 4 March 1941 and was a resounding success. The keylists for February were captured from the German armed trawler Krebs. This material allowed Hut 8 to decrypt the February traffic during March. Then thanks to the intelligence gained from this ‘break’ they were able to solve the April and May traffic cryptanalytically.

After decrypting the February and April traffic it was discovered that the Germans were keeping weather ships north of Iceland and in mid-Atlantic. The next operations targeted these ships as they would have cipher material onboard.

On 7 May ’41 the weather ship München was captured and the June keylists captured. On 28 June ’41 the weather ship Lauenburg was captured with the July keylists.

Another ‘pinch’ took place on 9 May when the U-boat U-110 was captured. The material seized included the Officer’s Enigma settings and the short signal code book (Kurzsignale).

These captures allowed Hut 8 to break into the Naval Enigma currently and familiarize itself with the structure and content of the messages. This information could then be used for cryptanalysis without the help of captured material.

In the second half of 1941 the Enigma decrypts allowed the British to route their convoys around the U-boat concentrations. Only 5 of 26 SC convoys, 2 of 31 HX convoys and 3 of 49 ON convoys were attacked. They were aided in this regard by the small number of U-boats operating in the Atlantic (16 for 4th quarter ’41). They also benefited from the German navy’s diversion of U-boats to the Mediterranean and the Baltic.

The drastic reduction in sinkings had baffled the Germans. They must have suspected that something was wrong since in February 1942 the 4-rotor M4 Enigma was introduced for the Atlantic U-boats. This was much more secure than the 3-rotor version and immediately put an end to the British success. British and American efforts to solve it failed again and again.

By December 1942 only 3 days traffic had been broken. This failure had strained relations between British codebreakers and the US navy’s OP-20-G. It was obvious that new 4-rotor ‘bombes’ were needed but the British reassurance that these would be soon introduced failed to materialize. The Americans then decided to build their own ‘bombes’ at the National Cash Register Corporation under engineer Joseph Desch. It was a good thing they did because the British 4-rotor ‘bombe’ design turned out to be problematic.

The introduction of the new ‘bombes’ took place in September 1943. From then on the naval Enigma settings would be solved within 24-48 hours.

However while the ‘bombes’ were being built the war was still going on. The Allies needed to break the new Enigma machine or their convoys would face horrible losses. Thankfully on 30 October 1942 the U-boat U-559 was heavily damaged of Port Said in the Med and before she sunk three British sailors managed to recover the Enigma and the short signal weather book. Two of them drowned when they went back to find more material.

Thanks to this material the Hut 8 codebreakers discovered a fatal flaw in the use of the Enigma by the Germans. When sending short signals they set the M4 ‘s fourth rotor at neutral position. This made the machine perform like the 3-rotor version. The Germans had built it this way so they could exchange messages between M3 and M4 versions (since the other services only had the 3-rotor version). Immediately the British work was dramatically reduced as they could use the short signals (such as weather reports) to find the position of only the 3 rotors. Once they did they could then find the position of the fourth rotor by checking the possible 26 positions by hand!

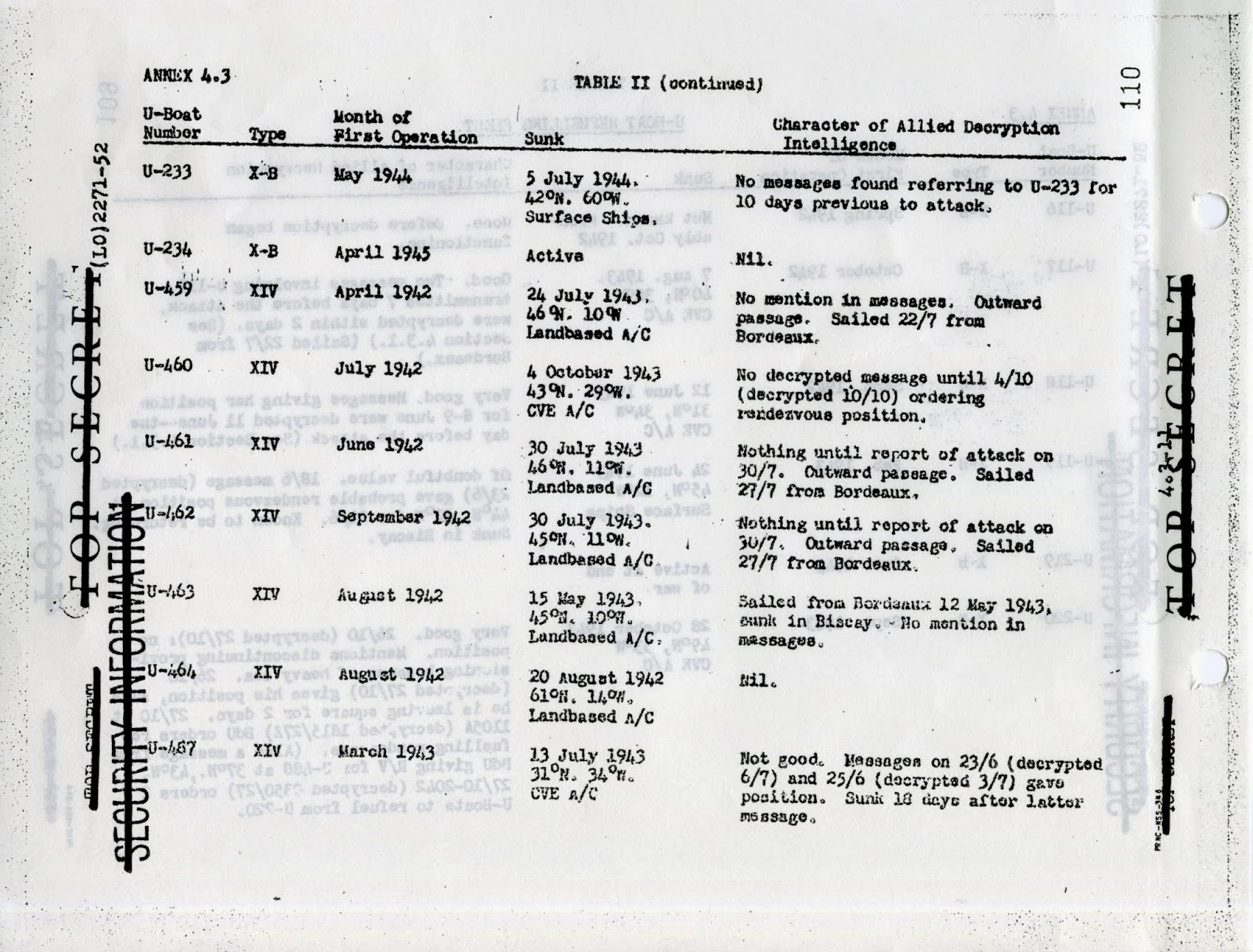

Thanks to these insights the Naval Enigma was once again being read. Still even with these advantages work was laborious and it took several days to recover the daily ‘key’. This limited the tactical value of the Enigma information. The official history says that messages older than three days could not be used in the field as the information was too old. This table from SRH-009 breaks down the days decoded by the time it took to break them (notice that the emphasis is on 2 days):

U-boat key Atlantic

|

| | | | | |

|

Days not broken

|

Days broken

|

Broken in 2 days or less

|

Between 2-5

|

Over 5

|

| | | | | |

Dec-42

|

12

|

19

|

5

|

3

|

11

|

Jan-43

|

3

|

28

|

5

|

12

|

11

|

Feb-43

|

1

|

27

|

18

|

5

|

4

|

Mar-43

|

5

|

26

|

8

|

11

|

7

|

Apr-43

|

11

|

19

|

12

|

7

|

0

|

May-43

|

3

|

28

|

9

|

5

|

14

|

Jun-43

|

9

|

21

|

1

|

6

|

14

|

Jul-43

|

2

|

29

|

2

|

1

|

26

|

Aug-43

|

6

|

25

|

1

|

9

|

15

|

Sep-43

|

4

|

26

|

3

|

16

|

7

|

The majority of the days were ‘broken’ too late for the information to be of use in the field. During the period December ’42 –May ’43 only one third of the ‘keys’ were solved in 2 days or less.

Even when the messages were decoded the coordinates they carried were enciphered with an additional system. In 1943 the grid system could be broken only with ad hoc analysis and with frequent mistakes.

Looking at the information presented so far it is obvious that in the period December ’42 to May’43 the value of Enigma intelligence cannot have been decisive. Moreover there were so many U-boats operating in the Atlantic that it was practically impossible to route the convoys around them (50 for 1st quarter ’43 compared to 16 in 4th quarter ‘41).

Instead other factors such as the use of new D/F equipment by the escort ships and radar by long range aircraft were decisive.

Conclusion:

Overall it is clear that the German naval strategy was to starve Britain of supplies. This required advance knowledge of the convoys routes and schedule.

The only way this could be achieved was through codebreaking. The B-Dienst was able to solve the Royal Navy codes in the Atlantic and there is no doubt that without this advantage the U-boats would not be able to locate the Allied convoys.

At the same time the codebreakers of Bletchley Park could not decode the naval Enigma or could decode it with considerable time lag. The only exception is the second half of 1941 when they indeed had a great success. In 1942 however they were blinded by the introduction of the 4-rotor Enigma.

In the first half of 1943 the German codebreakers had their greatest success against the convoy cypher. They could decode messages fast enough for the information to be used by the U-boat Command.

Their counterparts at Bletchley Park could also read their enemy’s communications but with too many problems and significant time lag. Even when the messages were decoded, use of enciphered coordinates by the Germans meant that Hut 8 had to spent additional time against this code. Clearly in this battle it was the B-Dienst that triumphed. Why did the U-boats lose then?

The answer is that by 1943 the U-boats were technologically obsolete. In the surface they could not survive against the Allied escorts. The Allied ships were equipped with new high frequency direction finding equipment and new mines. Escort carriers provided air cover. Long range recon planes with radar also hounded the U-boats forcing them to submerge or be destroyed. Their speed when submerged however was too slow to keep up with the convoys. The U-boats were not true submarines but submersible surface vessels.

No amount of codebreaking could change these facts. The last major effort by the U-boat command was clearly defeated by the Allies in May 1943. The catastrophic losses forced Doenitz to recall his U-boats from the Atlantic.

They would never again seriously threaten the Allied shipping routes.

Still their successes and the effect they had on Allied operations and strategy were definitely worth the effort.

The winner in the secret intelligence war in the Atlantic was the German side. The fact that they were defeated shows that even the greatest codebreaking successes cannot win wars on their own.

Sources: ADM 1/27186 ‘Review of security of naval codes and cyphers 1939-1945’ , HW 25/1 ‘Cryptographic History of Work on the German Naval Enigma’ by C.H.O'D. Alexander, British intelligence in the Second World War (4 volumes on operations) , SRH-009 ‘Battle of the Atlantic: Allied Communication Intelligence December 1942 - May 1945’ , Enigma Message Procedures Used by the Heer, Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine , Memoirs: Ten Years And Twenty Days , TICOM I-143 'Report on the Interrogation of Five Leading Germans at Nuremburg on 27th September 1945', ‘The German Naval grid in WWII’- Cryptologia article, Eagle in flames: the fall of the Luftwaffe, NSA history - ‘Solving the Enigma: History of the Cryptanalytic Bombe’, Bitter Ocean: The Battle of the Atlantic, 1939-1945, ‘Breaking Naval Enigma’ (Dolphin And Shark) , Wikipedia, SRH-368 ‘Evaluation

of the Role of Decryption Intelligence in the Operational Phase of the Battle

of the Atlantic, U.S. Navy OEG Report #68’

Acknowledgements: I have to thank Ralph Erskine for the S table statistics and for answering my many questions on naval codes.