In the course

of WWII the Allied and Axis codebreakers attacked not only the communications

of their enemies but also those of the neutral powers, such as Switzerland,

Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Ireland, the Vatican State and others (1).

Switzerland

was a traditionally neutral country but during the war it had close economic

relations with Germany and it also acted as an intermediary in negotiations

between the warring nations. Important international organizations like the Red

Cross and the Bank of

International Settlements were based in Switzerland.

Naturally

both the Allies and the Germans were interested in the communications of the

Swiss government.

Swiss

diplomatic codes and ciphers

The Swiss

Foreign Ministry used several cryptologic systems for securing its radio

messages. According to US reports (2) several codebooks were used, both

enciphered and unenciphered. These systems were of low cryptographic complexity

but had an interesting characteristic in that the same codebooks were available

in three languages.

French,

German and Italian were the recognized official languages of Switzerland. The

codebooks of the Swiss foreign ministry had versions in French, German and

English.

Apart from

codebooks the Swiss also used a number of commercial Enigma cipher machines at

their most important embassies.

The Swiss Enigma K cipher machine

Since the 1920’s the

Enigma cipher machine was sold to governments and companies that wanted to

protect their messages from eavesdroppers.

The latest

version of the commercial Enigma machine was Enigma K. In

WWII this device was used by the Swiss diplomatic

service and armed forces.

The device

worked according to the Enigma principle with a scrambler unit containing an

entry plate, 3 cipher wheels and a reflector. Each of the cipher wheels had a

tyre, marked either with the letters of the alphabet or with the numbers 1-26,

settable in any position relative to the core wheel, which contained the

wiring. The tyre had a turnover notch on its left side which affected the

stepping motion of the device.

The position

of the tyre relative to the core was controlled by a clip called Ringstellung

(ring setting) and it was part of the cipher key, together with the

position of the 3 cipher wheels.

The commercial version was different from the version used by the German Armed Forces in that it lacked a plugboard (stecker). Thus in German reports it was called unsteckered Enigma.

In 1938 the

Swiss government purchased 14 Enigma D

cipher machines, together with radio equipment. The next order was in 1939 for

another 65 machines and in 1940 they received 186 Enigma K machines in two

batches in May and July ’40. The Enigma cipher machines were used by the Swiss

Army, Air Force and the Foreign Ministry (3).

Military version

The majority

of the Enigma machines were used by the Swiss Armed Forces. Apparently the

Swiss were aware of the Enigma weaknesses so they modified their machines.

The wheels

were rewired and the stepping motion of the device was altered (4).

In regular

Enigma machines the movement of the rotors was predictable due to their having

only one notch. The fast rotor moved with every key depression, the middle

rotor moved once every 26 key depressions and the slow rotor (the left one)

moved only once every 676 key strokes (26x26).

The Swiss

military modified their Enigmas so that the middle rotor moved with every key

depression, instead of the one on the right.

During WWII

it seems that these security measures paid off since there is no indication

that either the Allies or the Axis were able to solve Swiss military Enigma

traffic.

US effort

The US and UK

effort was concentrated on the Swiss diplomatic Enigma traffic, thus it does

not seem like they were able to solve any military traffic.

The report ‘European

Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’, vol1 (dated May 1946) says in the ‘Results of European Axis cryptanalysis’ -

Switzerland that the Enigma traffic

SZD-1 was solved but not SZD-2 and SZD-3.

SZD and SZD-1

were diplomatic traffic and it is possible that SZD-2 and SZD-3 were the US

designations for Swiss military traffic.

The special

research history SRH-361 ‘History of the Signal Security Agency volume two -

The general cryptanalytic problems’ mentions, in chapters VII and XVI,

the Swiss diplomatic Enigma but not the military version.

Thus there is

no indication that the Anglo-Americans solved the military traffic.

German effort

During WWII

the German Army made extensive use of signals intelligence and codebreaking in

its operations against enemy forces. German commanders relied on signals

intelligence in order to ascertain the enemy’s order of battle and track the

movements of units.

The German

Army’s signal intelligence agency operated a number of fixed intercept stations

and also had mobile units assigned to Army Groups. These units were called KONA

(Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung) - Signals Intelligence Regiment and each

had an evaluation centre, a stationary intercept company, two long range signal

intelligence companies and two close range signal intelligence.

The KONA

units did not have the ability to solve complicated Allied cryptosystems.

Instead they focused on exploiting low/mid level ciphers and even in this

capacity they were assisted by material sent to them by the central

cryptanalytic department. This was the German Army High Command’s Inspectorate 7/VI.

Inspectorate

7/VI had separate departments for the main Allied countries, for cipher

security, cipher research and for mechanical cryptanalysis (using punch card

machines and more specialized equipment).

Swiss ciphers

were worked on by Referat 3 (France, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal), headed by Sonderführer

Hans Wolfgang Kühn. In the period 1941-42 this department solved Swiss hand

ciphers and did some research on the Swiss military Enigma (5).

The War Diary

of Inspectorate 7/VI shows that in 1941 Swiss traffic was intercepted and

worked on by the fixed intercept station Strasbourg (Festen Horchstelle Strassburg). Some hand ciphers were solved but

by late ’41 it was clear that the Enigma machine was entering service and that

it would replace the old cipher procedures.

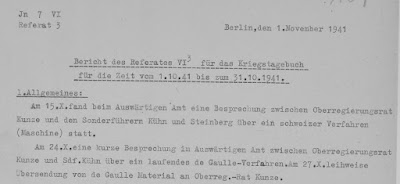

Report of

November 1941:

Referat 3

Schweiz

Der Spruchanfall der Schweiz ist sehr

gering geworden. Alle Anzeichen deuten darauf hin, dass die Schweiz das

Schwergewicht ihrer Verschlüsselungsmethoden auf die Maschine verlegt hat. Aus

Chi-Spruch inhalten geht hervor, dass die 'Enigma' in Verwendung ist.

(Vergleiche hierzu die VN-Meldungen: 1/41 Spruch)

Maschinensprüche liegen in geringer

Anzahl bereits vor und werden ständig beobachtet bis eine in Arbeit nahme

möglich wird.

In late 1941

and early 1942 there were several meetings with officials of the Foreign

Ministry’s deciphering department Pers Z in order to discuss the Swiss Enigma

problem.

In October

1941 Kühn (head of Referat 3) and

dr Steinberg (member of the mathematical research department) met the Pers Z’s

dr Kunze and discussed the Swiss Enigma procedure. The Inspectorate 7/VI

officials wanted to clarify if the military version of the Swiss Enigma used

the same wheel wirings as the diplomatic one. However due to the limited

intercepted traffic it was not possible to solve this issue.

Sonderführer Kühn

and dr Kunze met again in January

and March 1942. The March ’42 report says that an Enigma machine with Swiss

wheel wirings was loaned to the department for a short time.

Dr Buggisch, an Army cryptanalyst who specialized on cipher

machines, examined the Swiss Army messages and worked out a theoretical method

of solution which however depended on knowing the wheel wirings (6).

Despite these efforts the Swiss military Enigma was not

solved and from August 1942 Swiss radio traffic was monitored but not actually

worked on.

Diplomatic version

According to

US and German reports (7) the diplomatic Enigma was used on the links

Bern-Washington, London, Berlin, Rome.

The

diplomatic Enigma machines were rewired by the Swiss but their stepping system

was not modified.

During WWII

both the Anglo-Americans and the German codebreakers were able to solve Swiss Enigma

diplomatic traffic.

US/UK effort

The

codebreakers of the US Army Security Agency devoted most of their resources

against German and Japanese ciphers but they did not neglect to solve the

cryptosystems of neutral countries.

The postwar

report 'Achievements of the Signal Security Agency

in World War II’ (dated February 1946) says in page 31 that ‘The traffic of the Swiss Government provided

cryptanalytic problems of moderate difficulty and owing to the fact that the

Swiss served as representatives of belligerents in many countries, Swiss

traffic was an important source of information’.

Swiss crypto

systems were worked on by a sub unit of the Romance Language Code Recovery

section, created in December 1942. The Swiss unit was joined with the French

Code Recovery unit in March 1943 but in August 1944 it was made independent

again. The unit worked on the Swiss codebooks while the Enigma traffic was

solved by the machine cipher section and the results passed to the Swiss unit

for further processing. The Swiss Enigma was designated system SZD and work on it started in December

1942, with the first translations issued in July 1943 (8).

The US

codebreakers cooperated closely with their British counterparts on the systems

of neutral countries, including Switzerland. The British had better coverage of

European radio traffic and had been working on these systems for a long time.

Regarding the

Swiss Enigma traffic the British had exclusive coverage of the link Bern-London

and the Americans of Bern-Washington (9).

According to

US reports (10) messages were either in French, German or English and numbers

were sandwiched between X and Y with the figures 1234567890 substituted by the

letters QWERTZUIOP respectively.

Up to late

1942 the internal settings (wheel order and ring settings) were valid for a

week and the same key was used for the links Bern-Washington-London.

The cipher

machine employed only 3 wheels which the Anglo-Americans called ‘Blue’, ‘Red’

and ‘Green’. The wheels however were rewired frequently. One set was used for

the period August ’42 - 6 April ’43 then new wirings for the period 7 April ’43

- 31 December ’43 and the last one mentioned in the report covers the period

January ’44 – October’44. These wirings were received by the British

codebreakers (11).

Originally

the indicator (showing the starting position of the rotors) was sent in the

clear but from August 1942 it was enciphered. The cipher clerk chose a random position

for the wheels and enciphered the ring setting on it to produce the message’s

setting.

In 1943 the cipher

procedure was changed and a large set of numbered keys were used with the internal

key (wheel order and ring settings) being determined by the serial number of

the message. The indicator procedure remained the same, with the cipher clerk

choosing a random setting for the wheels and enciphering the ring setting on it

to get the message’s key. Different numbered keys were introduced for each

link.

From February

1944 some messages were doubly enciphered. The first indicator worked in the

manner already described previously. Then the cipher clerk chose another random

4-letter indicator, set the wheels on it and enciphered the text one more time,

including the first indicator. The second indicator was sent in the clear as

the first group and repeated anywhere within the first ten groups of text.

The messages

were sent in 5-letter groups with the first 4 letters being the indicator. Some

messages had the following coded designations: Saturn, Wega, Merkur, Helos, Nira, Urania. These were indicators of

content with Wega referring to shipping and transport matters, Saturn dealing

with trade and Merkur with finance.

Example of

Swiss telegram (12):

Solution of

the Swiss Enigma depended on the use of stereotyped beginnings and on operator

mistakes. The Enigma settings were recovered by using ‘cribs’ (suspected plaintext in the ciphertext) and sometimes ‘cillies’ (mistakes/non random choices by

the cipher clerks) (13).

Some of the

cribs used on the link Bern-Washington were: ‘Von Wanger fuer transport’, ‘Fuer transport’, ‘Pour transport’,

‘Transport’, ‘Wanger’, ‘Surcommerce’, ‘Fuer surcommerce’, ‘Handel’, ‘Ihr X’,

‘Unser X’, ‘Votre X’, ‘Fuer Wanger’, ‘Fortsetzung’.

IBM punch

card equipment was used to speed up the solution.

Occasionally

messages could be solved by using the indicators. As has been mentioned

previously each message had a 4-letter indicator, chosen by the cipher clerk.

After setting the wheels at the letters of the indicator the operator then

enciphered the ring setting on the machine in order to get the message key. The

4 letters of the external indicator were supposed to be chosen at random,

however sometimes the cipher clerks would choose the setting which they found

in their machine after setting up the ring setting clips. This was usually one

or two positions forward of the clip setting.

These non

random indicators could be exploited to solve the Enigma:

The Swiss

SIGABA

After

recovering the internal settings of the device and the message key it was

possible to decode the intercepted traffic.

Instead of

buying a commercial Enigma machine and rewiring it to Swiss specifications the

US codebreakers modified one of their SIGABA cipher

machines, thus turning it into a Swiss Enigma clone.

Content of

the messages

In general

Swiss diplomatic traffic was judged to be of low intelligence value. Most

messages dealt with Swiss trade, activities on behalf of the Red Cross,

prisoners of war, Swiss representation of interests of other countries,

conditions of neutrals in warring countries etc. Messages judged to be valuable

were those that dealt with Swiss trade, Swiss representation of the interests

of third countries and those concerning abuse of the Swiss diplomatic pouch.

Out of all

the Swiss crypto systems the Enigma cipher was the most important and in 1943

out of 906 Bern-Washington intercepts 266 were published in reports (14).

Effects of

improved security procedures

In 1943 the

introduction of a different rotor arrangement for each pair of messages

complicated the solution of Swiss Enigma traffic. From then on the US codebreakers

would have to identify the rotor order, the ring settings and the starting

position of the rotors for each two messages.

It seems that

due to the limited value of the Swiss messages and the significant resources

needed for regular solution of the individual key settings by late 1943 the

Swiss Enigma problem was downgraded in terms of importance and the traffic was

mostly used for training purposes. The keys to the Bern-London traffic were

received from the British (15).

German effort

Foreign

diplomatic codes and ciphers were worked on by three different German agencies,

the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, the

Foreign Ministry’s deciphering department Pers Z and the Air

Ministry’s Research Department - Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt.

OKW/Chi

effort

At the High

Command’s deciphering department - OKW/Chi, Swiss diplomatic systems were

worked on by a subsection of main Department V. Depending on the source this

was either Section 5 (France, Switzerland), headed by dr Helmuth Mueller or

Section 2 (Switzerland), headed by dr Peters (16).

According to

dr Erich Hüttenhain, chief cryptanalyst of OKW/Chi, the Swiss Enigma machine

was solved by his unit. The wirings of the wheels changed every 3 months but

they were not changed on all the links simultaneously. The machines on the link

Bern-Washington continued to use the old wirings for some time thus these

messages could be solved and they provided ‘cribs’ which could be used to solve

the Bern-London traffic and recover the new wirings (17).

The TICOM

report I-45 ‘OKW/Chi Cryptanalytic research on Enigma, Hagelin

and Cipher Teleprinter machines’ describes three methods for solving

the commercial Enigma machine.

1). By using

‘depths’ (messages enciphered on the

same wheel settings):

‘If 20 to 25 messages of the same setting are

available then the solution of these messages can be done in an elementary

manner ie, the columns of the encoded texts written under one another in depth

are solved as a Spaltencasar. In this the reciprocity of the substitutions is

made use of to a great extent. In the solution procedure no other

characteristic of the machine is used. This is also valid for the elementary

solution of Stocker Enigma. After this elementary solution of the encoded texts

the determination of the machine setting presents no difficulties.’

2). By using

a ‘crib’ (suspected plaintext in the ciphertext) and taking advantage of the

regular stepping of the Enigma. In the example given the crib ‘gabinetto alt’ is used:

3). By using

the E-Leiste (E-List) method. This method was based on comparison of the frequency

of the letter E in clear text and in

the examined cipher text. According to the report this was only a theoretical

solution and it was not used in practice since the ‘crib’ method sufficed:

‘With the K-machine six different wheel

orders are possible. The adjustable Umkehr wheel can be set in twenty-six

different positions. The periods of the three moveable wheels is about 17,000

steps, There are therefore 6 x 26 = 156 different periods of 17,000 long

respectively possible. If in each of the 156 different periods the clear letter

e is encoded 17,000 times, then 156 rows of encoded elements results, each

17,000 long. All these rows of encoded elements are designated e-Leiste.

The clear letter e appears in German

with a frequency of 18%. If a German clear text encode with the K-machine is

moved through the e-Leiste and if in each position the corresponding encoded

elements are counted, then the correct phase position will have the maximum

cases of correspondence. In this the Ringstellung need not be considered. The

e-Leiste need only be prepared once. The comparison of the encoded text with

the e-Leiste would have to be carried out on a machine. In order to come to a

positive conclusion in a reasonable time, then several machines would have to

be used at the same time, even if one machine was capable of making 10,000

comparisons per second.

In GERMANY a practical solution with

the aid of the e-Leist was not carried out, as in, practice the method of solution

from a part compromise was always possible.’

Pers Z

effort

At the

Foreign Ministry’s deciphering department Swiss systems were worked on by a

group headed by Senior Specialist dr Wilhelm Brandes. This section, which dealt

with French, Dutch, Belgian, Swiss and Romanian ciphers, successfully solved several

Swiss codebooks and the Enigma machine.

In TICOM

report I-22 ‘Interrogation of German Cryptographers of

Pers Z S Department of the Auswaertiges Amt’ (18) there is some

information regarding the Swiss Enigma.

In page 14 Dr

Rudolf Schauffler (head of Pers Z) said that ‘The commercial type Enigma used by the Swiss was sometimes solved by

stereotyped beginnings and known settings. The Swiss used to include in their

messages the machine settings for the next message’.

In page 20 it

says that ‘Dr. Brandes was unable to

state the exact dates when the Swiss Eniqma was read but said that it was read

completely for a considerable time. [Comment: the phrasing of his statement

implied that there was also a time when it was partially readable].

These statements

can be confirmed by the Pers Z file ‘Bericht

der Belgisch-Französisch-Schweizerischen Gruppe Stand 31.12.1941’ (19)

since it contains reports that mention the Swiss Enigma traffic.

The report of

Group Brandes for 1940 says that most of the Swiss diplomatic traffic was sent

using letter codebooks. However from the end of May 1940 traffic between

Bern-Berlin and Bern-London had been sent using the Enigma machine. According

to the report ‘a solution should be

possible with ample material and sufficient personnel’.

According to

the report for 1941 the Swiss Enigma was solved thanks to a partial solution

provided by the Forschungsamt. In order to process this traffic two Enigma

machines were purchased and rewired according to the Swiss specifications and

the results passed on to the FA. In some cases the inner settings of the device

were given in the telegrams. The machine was used on the links Bern - Berlin,

London, Washington.

Apart from

the Forschungsamt’s assistance there was also exchange of information between

Pers Z and Inspectorate 7/VI on the Swiss Enigma. A detailed report on the

solution of the commercial Enigma was found in the Pers Z files (20). This was

written by Inspectorate 7/VI mathematician dr Rudolf

Kochendörffer (21). It involved obtaining many messages in depth, reading

these messages by solving the successive (monoalphabetlc) columns of

superimposed text and then applying the resultant cribs to recovering the

wirings of the rotors.

Forschungsamt

effort

At the Air

Ministry’s Research Department Swiss systems were worked on by Abteilung 8,

Branch A, Section 3 (Holland,

Switzerland, Luxembourg, Abyssinia). The department had about 30-40 workers

(22).

According to

dr Martin Paetzel (deputy director of Main Department IV - Decipherment) ‘their main machine success was with the

Swiss Enigma as long as the same machine setting was used over a longish period’

(23).

More details

about the Forschungsamt solution of the Swiss Enigma are given by Bruno Kröger

in TICOM reports DF-240 and DF-241 (24). Kröger was the FA’s cipher machine

expert and during the war he solved several foreign cipher machines.

The Swiss

Enigma was first solved as a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, by processing

several messages sent on the same key. The solution of these ‘depths’ led to

the recovery of the wheel wirings and the further exploitation of the traffic.

When the wheels were rewired it was possible to recover the new settings by

using assumed plain text-cipher text cryptanalytic attacks. It took 5-6 workers

about 1-6 weeks to recover the wiring of the first rotor and then they could

quickly recover the wiring of the remaining two rotors.

Eventually

the use of enciphered indicators and individual internal keys for each message

(or pair of messages) made it too costly to work on this traffic, so the FA had

to give up on it. According to Kröger this decision was made in early 1944.

Postwar

developments – The new cipher machine and dr Kröger’s confession

At the Swiss

Army’s Cipher Bureau (headed by Captain Arthur

Alder, a professor of mathematics at the University of Bern) a new cipher

machine was designed in the period 1941-43, for use by the country’s armed forces and

diplomatic authorities (25).

The device

was based on the Enigma principle with a scrambler unit containing wired rotors

and a reflector. However the new cipher machine, called NEMA, had a much more

complex stepping system than standard Enigmas. The device had 10 rotors, out

which 4 were the alphabet rotors, 1 was a reflector that could move during

encipherment and 5 stepping wheels controlling the motion of the device.

The NEMA (Neue Maschine) was much more secure than a commercial Enigma

machine and it entered service in 1947.

In 1948 a

letter was sent to the Swiss government. The letter was written by dr Kröger,

the Forschungsamt’s cipher machine expert, and in it he described how the Swiss

Enigma was solved during the war. His conclusion was that the commercial Enigma

could not satisfy the current security

requirements. Kröger then offered his services to the Swiss

government (26).

Notes:

(1). Intelligence

and National Security article: 'No immunity: Signals intelligence and the European

neutrals, 1939-45', The

Irish Government Telegraph Code, Wartime

exploitation of Turkish codes by Axis and Allied powers, The

Pope’s codes

(2). European

Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II, vol1 table ‘Results of European Axis cryptanalysis’ and US report ‘Swiss Cryptographic Systems’ (found in NARA

- RG 457 - NR3254 'Foreign Cryptographic Systems, 1942-1945')

(3). Cryptologia

article: ‘Enigma variations:

an extended family of machines’

(4). Cryptologia

article: ‘Enigma variations:

an extended family of machines’

(5).

Kriegstagebuch Inspectorate 7/VI - German Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive

- TICOM collection – files Nr 2.755-2.757

(6). TICOM

I-176 ‘Homework by Wachtmeister Dr. Otto Buggisch of OKH/Chi and OKW/Chi’,

p3

(7). US report ‘Swiss

Cryptographic Systems’ and German

Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive - TICOM collection - file Nr. 2.050 - Berichte Gruppe Frankreich, Belgien,

Holland, Schweiz, Rumänien 1939-1942

(8). SRH-361

‘History

of the Signal Security Agency volume two - The general cryptanalytic problems’,

chapters VII ‘The Swiss systems’ and XVI ‘The machine cipher section’.

(9). US

report ‘Swiss Cryptographic Systems’,

p3

(10). NARA -

RG 457 - Entry 9032 - files NR3820 ‘Swiss

diplomatic machine cipher SZD’, NR3821 ‘Swiss random letter traffic’, ‘SZD various notes’, NR3254 ‘Swiss Cryptographic Systems’

(11). NR3820

‘Swiss diplomatic machine cipher SZD’,

p23

(12). NR3820

‘Swiss diplomatic machine cipher SZD’,

p6

(13). NR3820

‘Swiss diplomatic machine cipher SZD’,

p3-5

(14). NR3254 Swiss Cryptographic Systems’, p4-5

(15). ‘SZD various notes’, NR3254 Swiss Cryptographic Systems’ and SRH-361

‘History of the Signal Security Agency volume two - The general cryptanalytic

problems’, pages 237-238.

(16). TICOM

I-123, p3 and TICOM

I-150, p2

(17). TICOM

I-31 'Detailed interrogations of Dr. Hüttenhain, formerly head of research

section of OKW/Chi, at Flensburg on 18-21 June 1945’, p14

(18). TICOM I-22,

paragraphs 113, 160 and 163

(19). German

Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive - TICOM collection - file Nr. 2.050 - Berichte Gruppe Frankreich, Belgien,

Holland, Schweiz, Rumänien 1939-1942

(20). ‘European

Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ vol 2, p76

(21). TICOM

report DF-38 ‘The

Enigma’ (from Frode Weierud's

CryptoCellar)

(22). TICOM I-54,

p2 and TICOM DF-241

‘Part 1’, p10

(24). TICOM DF-240-B

‘Analysis of the Enigma cipher machine type K’, DF-240

’Parts III and IV’, p14-15 and DF-241

‘Part I’, p23

(25). Cryptologia

article: ‘The Swiss NEMA Cipher

Machine’, Das

Rätsel um die «Neue Maschine»

Acknowledgements: I have to thank Frode Weierud for sharing the reports

‘Swiss diplomatic machine cipher SZD’,

‘Swiss random letter traffic’, ‘SZD various notes’.

Additional

information:

The E-List

method mentioned in TICOM report I-45 was also known to the US codebreakers.

Their solution is described in the report ‘Suggested

general solution for the commercial Enigma, where only the end plate and wheel

wirings are known’ (available from the NSA’s Friedman Collection)

"In 1941, the Swiss found out that the French had broken some of their Enigma traffic. The machines used by the Swiss Army were subsequently modified by altering the stepping mechanism."

ReplyDeletehttp://www.cryptomuseum.com/crypto/enigma/k/swiss.htm