During the

war Turkey, as a neutral power, had a major advantage since it could operate

embassies in both Allied and Axis nations. This gave Turkish officials the

opportunity to get valuable information from both sides. For this reason

Turkish diplomatic communications became a target for Axis and Allied

cryptanalysts.

The Turks

used mainly 4-figure codebooks (INKILAP, ZAFER, SAKARYA, CANKAYA, INONU, ISMET)

enciphered with additive sequences.

Turkish systems

were attacked by several German agencies. The diplomatic codes were attacked by

the Pers Z, Forschungsamt and OKW/Chi. Military systems by the OKL Chi Stelle,

the Army’s Inspectorate 7/VI and OKW/Chi.

Italy,

Hungary and Finland also read Turkish traffic with significant success

throughout the war.

All the Axis

powers took advantage of the fact that some of the Turkish codebooks were simply

repaginations of previous versions.

German

effort

The codebreaking

department of the Foreign Ministry - Pers

Z attacked Turkish diplomatic systems since 1934. These were continuously

solved till the end of the war. There was a separate department for Turkish

traffic headed by Dr. Hermann Scherschmidt.

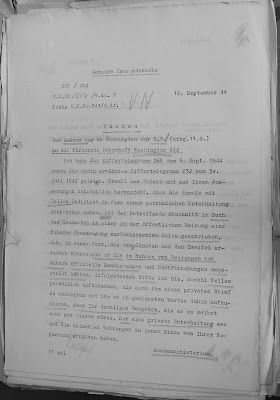

Goering’s Forschungsamt also read Turkish

diplomatic traffic, especially that of the Moscow embassy.

The

codebreaking department of the Armed Forces High Command - OKW/Chi dealt with Turkish military and diplomatic traffic with

good results. The Turkish desk had about 10 people and was headed by Dr Locker.

According to Mettig, second in command of OKW/Chi in the period 1943-45, the

solution of the Turkish traffic (especially from London, Paris and Moscow) was

one of the major OKW/Chi achievements during the war.

The

Luftwaffe’s OKL Chi Stelle monitored

Turkish AF traffic. According to chief cryptanalyst Ferdinand Voegele three simple

systems were solved by forward units.

OKW/Chi

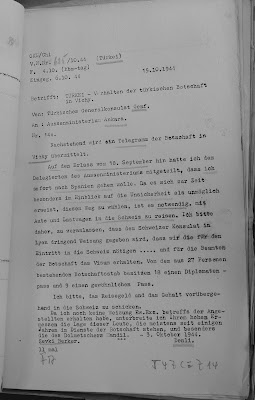

decodes of Turkish diplomatic traffic can be found in the TICOM collection of

the German Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive.

The Army’s

signal intelligence regiment KONA 4

monitored Turkish traffic both military and police. The central agency OKH/Inspectorate 7/VI read Turkish

systems and shared results with the Forschungsamt. One of the codes read was

that used by the Turkish president when onboard the state yacht ‘Savarona’. Army

cryptanalyst Dettmann, head of cryptanalysis in the Eastern Front, says in

DF-112 that the results of the Yalta conference became known to the Germans

through Turkish messages.

The war diary of Inpsectorate 7/VI shows that Turkish codes were constantly read. For example:

The war diary of Inpsectorate 7/VI shows that Turkish codes were constantly read. For example:

Report of

October 1942

Report of May 1943

Most of this traffic was solved by forward units. The reports of KONA 4 (Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung - Signals Intelligence Regiment) which covered traffic from the Balkans and the Middle East show that Turkish military and police codes were solved in 1943-44.

In 1944 1.002 messages were solved in the first quarter and 1.200 in the second.

Italian effort

Hungarian

effort

The Hungarians

put special emphasis on the solution of Turkish traffic and assigned their best

cryptanalyst Titus Vass to the Turkish desk.

Finnish

effort

The Finnish

codebreaking department devoted a third of its cryptanalysts on Turkish

traffic with the result that all the 4-figure codes were read. For example:

Allied

effort

The Western Allies

were also interested in the Turkish diplomatic communications.

The US Army’s

Signal Security Agency started

attacking Turkish and Arabic traffic in 1942. Its official history ‘Achievements of the Signal Security Agency in

World War II' says:

‘Late in 1942 work was initiated on the

systems of those governments who use the Arabic and Turkish languages. After a modest beginning the traffic of the

following governments was read: ‘Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi

Arabia, Syria, Transjordan, and Turkey. Of these, by far the most Important in

production of valuable information and in extent of the task of solution were

the Turkish systems.’

The British codebreakers also exploited Turkish traffic. Britain had

been reading Turkish traffic for decades and continued to do so during WWII. Diplomatic

traffic was worked on not at the famous Bletchley Park facility but at the Diplomatic section in Berkeley Street,

London. The embassies monitored were London, Kuibyshev, Teheran,

Budapest, Lisbon, Rome, Madrid, Stockholm, Berlin, Washington, Vichy, South

America, Helsinki, Bucharest, Sofia and Tokyo. Results were shared with the Americans. Decoded messages

allowed them to keep an eye on Turkish-German relations and Soviet territorial

demands.

It’s

interesting to note that in 1944 the Brits had come to the conclusion that the

insecurity of Turkish codes was becoming a problem since the Axis forces would

also read these messages and gain valuable information. The British authorities

wanted to send two cipher experts to convince the Turks to upgrade their

systems but it doesn’t seem like the Turks considered this a good idea. The

summary of report FO 850/135

says: ‘Refusal by the Turkish Government

to receive two British cypher experts to advise on diplomatic and internal

cyphers’...

Conclusion

Turkish codes

seem to have yielded against anyone who was willing to invest the necessary

resources against them. Even though Turkey was not that important politically

or economically the fact that it had embassies in Axis and Allied capitals made

its traffic valuable for all the major participants of the war.

The Axis gained information of great value

especially from the Moscow embassy. The Allies used the decrypts in order to

monitor Turkish foreign policy towards Germany and counter Soviet efforts to

change the legal status of the Turkish Straits.

Sources: TICOM reports I-22, I-63, I-103,

I-119, I-128, DF-187B, DF-112, ‘European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War

II’ volumes 3,4,5,6,7 , Intelligence and National Security article: ‘No

immunity: Signals intelligence and the European neutrals, 1939-45’, International Journal of Intelligence and

Counter-Intelligence article: ‘Left in the Dust: Italian Signals Intelligence,

1915-1943’, 'In the Name of Intelligence: Essays in Honor of Walter Pforzheimer',

‘The Achievements of the Signal Security Agency (SSA) in World War II’, Intelligence

and National Security article: ‘Diplomatic Sigint and the British Official Mind

during the Second World War: Soviet claims on Turkey, 1940-45’, war diary of Inspectorate 7/VI and KONA 4.

Acknowledgements: I have to thank Ralph Erskine for

information on the British exploitation of Turkish codes.

Hello Christos

ReplyDeleteI have a question for you about codebreaking more generally in ww2

(greg mcnulty here btw)

The british obviously used codebreaking to assist the campaign against Rommel.

Rommel benefitted from signals intel , codebreaking, lack of security etc - which was obviously well known in the senior german command of navy and Luftwaffe.

Hence I find it tough to understand the post war conventional wisdom

"Rommel was a great commander" view of the british - was this to cover there own failures?

Also the "germans would never believe their enigma could be compromised" hence "Italians were leaking information to the british" etc

Why wouldn't the germans and Italians be circumspect about their own code security given their own experience of the benefits of reading enemy codes - and the resources they were hence willing to throw at codebreaking. Also they knew something of the polish work on enigma ?

So we have this "Rommel was a genius" ; "germans could not conceive of enigma weakness"; "germans thought Italians were traitors" nonsense.

‘The british obviously used codebreaking to assist the campaign against Rommel’

DeleteUndeniably true, although it seems their successes have been wildly overrated.

‘Rommel benefitted from signals intel’

Again, undeniably true. I think this was true for all German commanders (not only sigint but also photo reconnaissance by the LW).

‘"Rommel was a great commander" view of the british - was this to cover there own failures?’

Rommel was a great commander, I don’t think anyone can deny that. Obviously the Brits exaggerated his performance in order to hide their own failures. However postwar he was criticized for moving his forces too far from his supply bases (fuel shortages etc) and for commanding his troops from the front, which often led to him being out of contact with his subordinates.

‘Why wouldn't the germans and Italians be circumspect about their own code security given their own experience of the benefits of reading enemy codes’

WWII cipher security for all participants is a complicated subject. Regarding the statements on Enigma I think it’s simply a matter of historians not doing their work properly and of course of relevant material remaining classified for too long.

thank you - interesting as always - gm

ReplyDelete