Details of their successes against enemy codes have been hard to find because after Japan’s surrender, in September 1945, they had time to destroy their records and disperse their personnel. Still the few remaining documents in Japan combined with decoded Japanese messages found in the British archives can provide a basis for assessing their operations during the war.

Japanese Army agency

The

beginnings of a centralized army cryptologic service date back to 1921 when a

study group comprised of Army, Foreign Ministry and Ministry of communications

cipher specialists was formed to work towards the solution of US and British

codes. In 1922 the

Japanese were involved in negotiations with the Soviet Union regarding their forces in

Siberia. At that time the crypto service was successful in solving the code of

the Soviet delegation. This success proved the importance of codebreaking and

more resources were assigned to that department.

Foreign

assistance was obtained from the Polish cryptologic service which had an

excellent record versus Soviet codes. Captain Kowalewski of the Polish army was

invited to Tokyo in 1923 and a small group of Japanese officers were sent to

Poland to study. It was this

group that formed the basis of the Army’s codebreaking department. By 1936 this

department (which often changed designation) had 135 people.

The main

effort of the army agency was against Soviet and Chinese codes. This made sense

as army units were fighting against the Chinese army and there were a series of

border engagements with the Soviet armed forces in Manchuria. Chinese Kuomintang military and diplomatic codes were solved and

they gave the Japanese valuable intelligence on upcoming operations and

diplomatic initiatives. For example the movement of 54 Chinese divisions in

1940 was detected and followed by solving the Chinese army’s 4-figure code

Mi-ma. At the same

time the solution of Soviet military and NKVD border unit codes allowed the

Japanese to keep a close eye on Soviet dispositions, training and supply in the

East. Codebreaking gave them an advantage prior to the Battle of Lake Khasan.

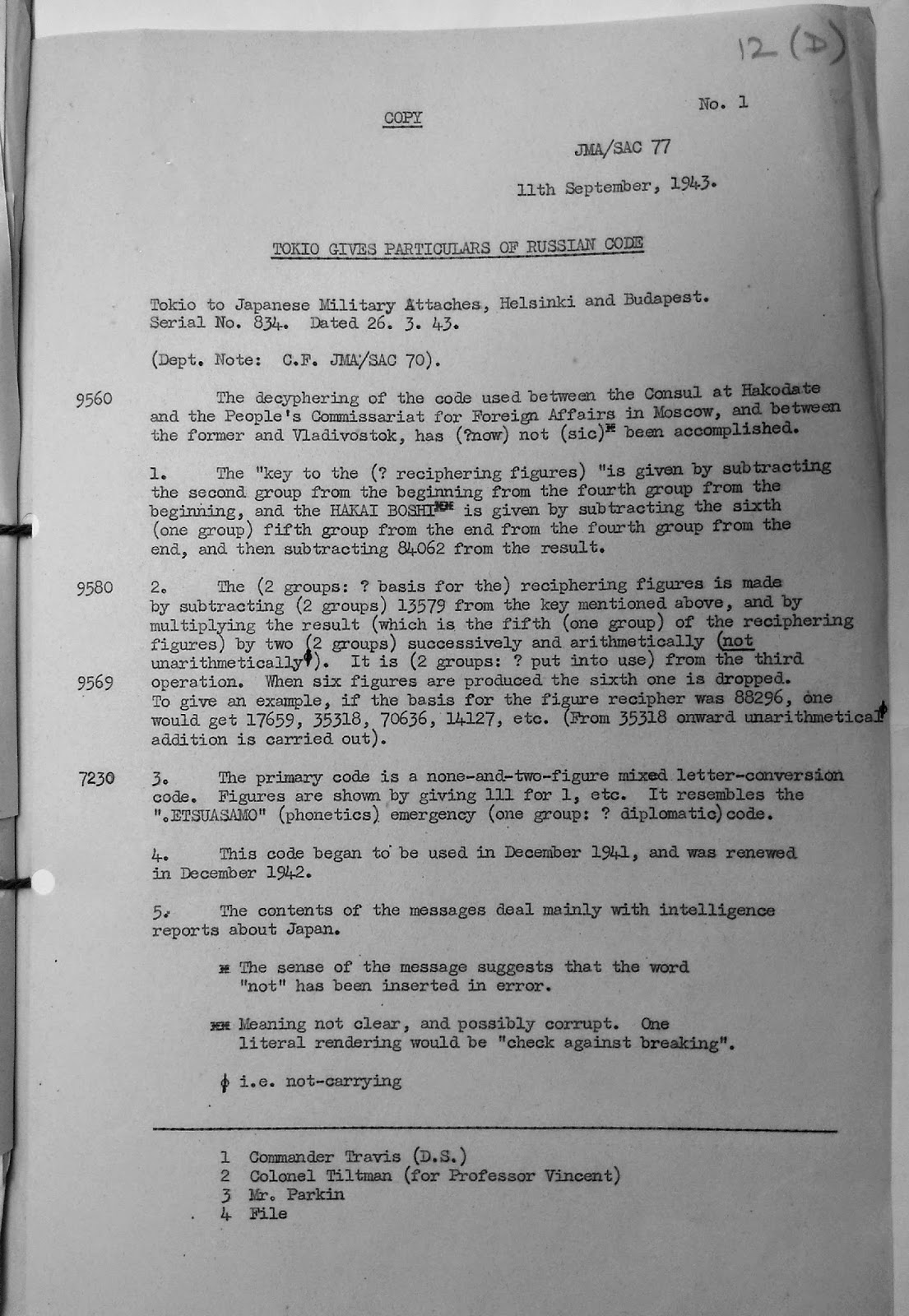

From 1943 onwards the Japanese could solve the Soviet diplomatic code

used by the embassies/consulates in Seoul, Dairen, and Hakodate for

communications with Moscow and Vladivostok. In Harbin, China a spy inside the Soviet embassy gave them copies of

intelligence reports coming in from the Soviet embassy in Australia.

The Japanese

were helped in their efforts through black bag

operations. In the late

1930’s the US diplomatic codes Brown and M-138-A strip were copied by a unit of

the Military police. British

diplomatic systems Cypher M, Interdepartmental and R code were also physically

compromised. These systems allowed the Japanese to read the communications of the US

and British ambassadors in the period 1940-41. The Interdepartmental Cypher provided valuable intelligence on the

state of British defenses in Malaya.

During WWII

Army codebreakers were forced to devote resources to the codes of the United

States. Apart from low level codes the M-209 cipher machine was successfully analyzed

and decoded in late 1944. Bombing missions of the B-29’s were betrayed through

their use of the M-209.

In 1944 a

major effort was made to improve performance by recruiting university students

from mathematics and foreign language departments. Also in the same period IBM

punch card equipment was used for cryptanalysis. These efforts came too late to

have an impact on the war situation but they show that the Japanese leadership

understood the value of secret intelligence.

Japanese Navy agency

The Japanese

Navy’s signal intelligence agency was older than the army’s and its beginnings dated

back to the Russo-Japanese war of 1905. A centralized codebreaking department

was formed in 1929 to attack US and British communications.

The Navy’s

efforts were directed mainly against the United States. The naval codebreakers

were able to decode the US diplomatic codes Gray and Brown but unlike their

Army counterparts they could not solve the high level M-138-A. Against

British diplomatic codes they had very limited success. By reading

the Anglo-American diplomatic codes they could see the rising tension in the relations

between Japan and the US in the 1930’s.In order to keep an eye on US fleet movements several monitoring stations were operated prior and during the war. An interesting case was the undercover L agency. In 1938 a small unit called the ‘L Agency’ (L-Kikan) was established in Mexico to monitor US Fleet traffic in the Atlantic and also the commercial RCA radio from New York City.

During the Pacific war most US military codes proved secure. There was only limited success with the US Navy’s CSP-642 strip cipher. However the codes used by merchant ships had been received from the Germans and their enciphering tables were solved in Japan.

The Japanese

were able to track the movement and concentrations of merchant ships and thus

anticipate major allied operations by reading the Merchant Navy Codes. They

also came to rely more and more on D/F and traffic analysis for tracking enemy

fleet movements.

Against

Soviet systems they were able to solve the codes used by Soviet Merchant Navy ships in Kamchatka and Vladivostok.

In general

the performance of the Naval codebreakers versus enemy codes was not as

successful as that of their Army counterparts.

Foreign Ministry’s decryption

department

Information

on the decryption

department of the Japanese Foreign Ministry is limited since

their archives were destroyed twice during the war. First in a bombing on 25

May 1945 and then in August 1945, when they were ordered by their superiors to

burn all secret documents.

According to the recently declassified TICOM report DF-169 ‘Cryptanalytic section Japanese Foreign Office’ this department was established in 1923 and by the end of WWII had approximately 14 officials and 16 clerks. The radio intercept unit supplying it with messages had a station in Tokyo equipped with 10 receivers and 19 operators. They usually intercepted 40-60 messages per day with 100 being the maximum.

The emphasis was on the solution of the codes of the United States, Britain, China and France but some German, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, Swiss, Thailand and Portuguese codes were also read. Despite their limited resources it seems that the Foreign Ministry’s codebreakers were able to achieve their goals mainly thanks to compromised material that they received from their Army and Navy counterparts.

Japanese radio security services

The identification

of agents’ radio transmissions and their location through direction finding was

the job of specialized radio security units. In Japan

there were two agencies that carried out this mission. One was the Science

group of the War Ministry’s Investigation department - Otsu-han. The other was

a similar department of the military police Kenpei-Tai.According to the recently declassified TICOM report DF-169 ‘Cryptanalytic section Japanese Foreign Office’ this department was established in 1923 and by the end of WWII had approximately 14 officials and 16 clerks. The radio intercept unit supplying it with messages had a station in Tokyo equipped with 10 receivers and 19 operators. They usually intercepted 40-60 messages per day with 100 being the maximum.

The emphasis was on the solution of the codes of the United States, Britain, China and France but some German, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, Swiss, Thailand and Portuguese codes were also read. Despite their limited resources it seems that the Foreign Ministry’s codebreakers were able to achieve their goals mainly thanks to compromised material that they received from their Army and Navy counterparts.

Japanese radio security services

There were

also radio security units with the Japanese armies in China. The military

police of the Kwantung Army had a D/F group called ‘Unit 86’. The military

police of the Expeditionary Army to China had a similar group named ‘6th

Section’. This group was able to locate Soviet radio spies in Shanghai during

the war.

Cooperation with foreign powers

An important

aspect of the Japanese approach to intelligence was their effort to cooperate

with other countries. They were able to gain allies in two ways. One was by

offering stolen enemy codes. The other was by spending lots of money.

During WWII

the Japanese had huge sums of money available for intelligence operations.

German intelligence officers commended on the ease with which their Japanese

counterparts could acquire and spend large funds. At the same time copied US and British codes were shared with their

German Allies in exchange for other cryptosystems.

Cooperation

with the Germans

The Japanese had received valuable material from the Germans in November

1940 when a party from the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis boarded the British SS Automedon and captured top secret documents. Among them was a copy of the British War Cabinet minutes of August 1940. These files gave a summary of the British Far Eastern strategy and admitted that Thailand and Hong Kong were indefensible. They also indicated that Britain would not go to war with Japan over the fate of French Indochina. These documents were given to the Japanese and allowed them to correctly assess the weakness of the British in the Far East. The captain of Atlantis, Bernhard Rogge, was given a samurai sword for this success!A Japanese mission headed by Colonel Tahei Hayashi, former head of the Army’s cryptologic agency visited Germany in 1941 and exchanged US and British codes with systems solved by the Germans. This promising start did not lead to closer cooperation as communications between Japan and Germany were problematic. Moreover the Germans did not trust the Japanese with their most recent codebreaking successes. Things changed in summer ’44, when under Hitler’s orders several high level systems (including the latest strips for the M-138-A cipher) were given to the Japanese.

According to Wilhelm Fenner, head of the cryptanalysis department of OKW/Chi, about 200 decoded messages were passed on to the Japanese in 1944-45. For example:

Cooperation

with the Finnish cryptologic service

Major Eiichi

Hirose was sent to Finland to exchange results with their codebreakers. Also General

Makoto Onodera who was military attaché in Stockholm financed the Finnish

crypto service in exchange for copies of their work. The Finnish

codebreakers were successful in solving several Soviet and US State department

codes (especially the M-138-A strip cipher). These were passed on to the Japanese. For example: In September 1944 Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. Paassonen and Hallamaa anticipated this move and fearing a Soviet take-over of the country had taken measures to relocate the radio service to Sweden. This operation was called Stella Polaris (Polar Star). Roughly 700 people, comprising members of the intelligence services and their families were transported by ship to Sweden. The Finns had come to an agreement with the Swedish intelligence service that their people would be allowed to stay and in return the Swedes would get the Finnish crypto archives and their radio equipment. Their archives were also sold to the Japanese military attaché Makoto Onodera.

Cooperation

with the Hungarians

Lieutenant

Colonel Shinta Sakurai was sent to Hungary to cooperate with that country’s

crypto service.

Use of

Polish codebreakers

Cooperation

between Japan and Poland in the cryptologic field dated back to the 1920’s.

After the fall of Poland some Polish exiles were employed by the Japanese at

the attaché office in Rumania, where they worked on Soviet codes.

Overview of major codebreaking

successes

Soviet

codes

Messages from

Soviet Merchant Navy ships in the coastal areas of Kamchatka and Vladivostok were read by the Japanese.

The Soviet diplomatic code used in the East by consulates/embassies in Seoul, Dairen, and Hakodate for their communications with Moscow and Vladivostok was read by the Japanese from 1943 onwards. This was not the standard Soviet diplomatic system of codebook plus one time pads but a simpler system

Intelligence reports from Australia were copied by a Japanese spy working in the Soviet embassy in Harbin, China. These messages came from Soviet agents in the Australian government and contained information on Allied political and military plans.

USA codes

The M-209

cipher machine was the US version of the Hagelin C-38 and it was used

widely by the US armed forces as a mid-level cryptosystem. The Army used it at

division level and the USAAF used it for operational and administrative

traffic. The Japanese codebreakers investigated this traffic in 1944,

identified the use of a Hagelin type device and were able to solve messages in

‘depth’ (enciphered with the rotors at the same starting position). US Army

messages were read, especially during the Philippines campaign of 1944-45. The

mathematician Setsuo Fukutomi who worked in the cryptology department wrote: ‘These M209 encoding-machines were in general

use at the front divisions of the American armed forces. The General Staff of

the Japanese Army had bought a prototype of this machine in Sweden before the

war. The military engineer Yamamoto mentioned above guessed that “M209” was an

adaptation of this Swedish prototype. He could even determine the details of

the modifications of the prototype that had produced M209. At that time, I was

serving as a soldier working at the General Staff. I noticed that the keys of

the codes of the M209 were so-called “double keys”, and I succeeded in breaking

these double-keys. After that, a team including a number of drafted officers

including myself were sent to the Philippines. We managed to obtain some good

decoding results, but the way the Americans made the daily change of coding

keys was such that we were unable to break their codes every day, which

strongly restricted the benefits we earned from our work’.

USAAF

messages referring to operations of the B-29 bombers were also decoded by the

Japanese.

The Merchant

Navy Code and the Merchant Ships Code were received from the Germans and the

enciphering tables broken in Japan. These were used from 1940 till the end of the war.

By reading these codes the Japanese were able to identify the concentration of

shipping in specific areas and deduce that major Allied operations would

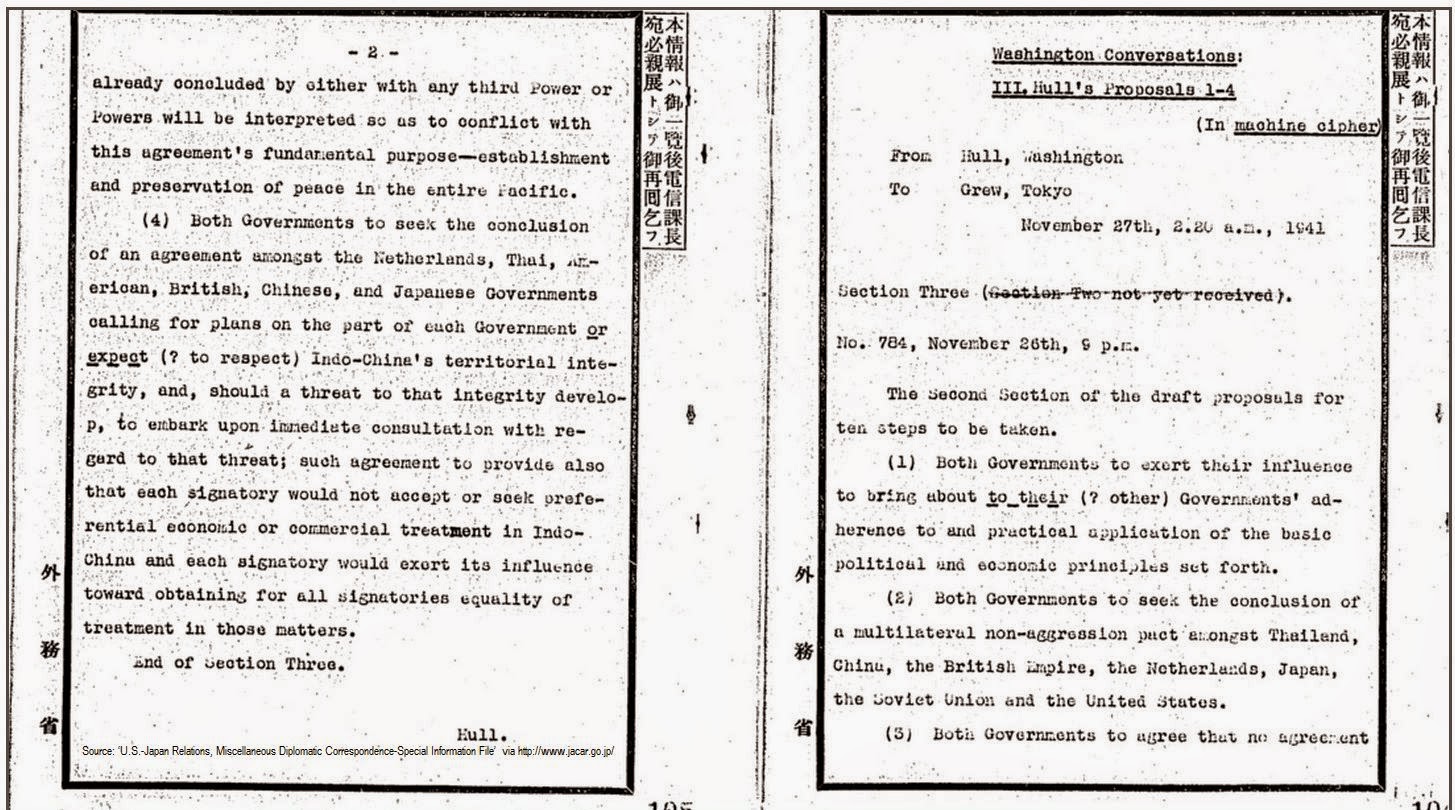

follow.State Department codes Gray, Brown, A1 and the M-138-A strip cipher were read by the Japanese with varying degrees of success. All these systems had been physically compromised. Through these systems the messages of the US ambassador in Japan Joseph Grew, as well as other embassies abroad, could be solved.

Success with the high level M-138-A in 1943-44 depended on help from the Finns and the Germans.

British

codes

The diplomatic systems Cypher M,

Interdepartmental cypher and R code were physically compromised. The British

Interdepartmental cypher provided intelligence for the Malaya campaign. Through these

systems the messages of the British ambassador to Japan Robert

Craigie could be read in the years

1940-41. This was stated by General Hideki Tojo (Prime Minister during the

period 1941-44). British diplomatic messages can be found in the archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry in the file ‘U.S.-Japan Relations, Miscellaneous Diplomatic Correspondence-Special Information File’:

Chinese codes

The code of

the Chinese Communist party was much harder to solve but it was read at times

and provided advance knowledge for a number of communist offensives.

Sources:

‘Japanese

Intelligence in World War II’ by Ken Kotani, ‘Combined Fleet Decoded’, HW

40/29 ‘Exploitation of Russian Civil communications by Axis Powers’, HW 40/75

‘Enemy exploitation of Foreign Office codes and cyphers: miscellaneous reports

and correspondence’, HW 40/85 ‘Exploitation of British

Inter-Departmental cypher’, DF-187D ‘Relations of OKW/Chi with foreign cryptologic

bureaus’, DF-187F ‘Remarks made by Ministerialrat Fenner in reply

to certain questions of a general nature’, DF-169

‘Cryptanalytic section Japanese Foreign Office’, ‘Hitler's Last Chief of

Foreign Intelligence. Allied Interrogations of Walter Schellenberg’, HW 40/7 ‘German Naval Intelligence

successes against Allied cyphers, prefixed by a general survey of German

Sigint’, HW 40/132 ‘Decrypts

relating to enemy exploitation of US State Department cyphers, with related

correspondence’, HW 40/221 ‘Poland:

reports and correspondence relating to the security of Polish communications’, ‘The

Codebreakers – The Story of Secret Writing’, ‘Mathematics

and War in Japan’, National Institute for Defense Studies articles: ‘Japanese intelligence and the Soviet-Japanese border conflicts in the 1930s’, ‘Japanese Intelligence and Counterinsurgency during the Sino-Japanese War: North China in the 1940s’, ‘Onodera

interrogation vol2-22 - CIA FOIA’, Naval history magazine article: ‘How

the Japanese did it’, US Navy report: ‘Japanese Radio

Communications and Radio Intelligence’,

Diplomatic

records Office, Tokyo, ‘U.S.-Japan Relations, Miscellaneous Diplomatic Correspondence-Special

Information File’ (A-1-3-1, 1-3-2) via JACAR (file link), The Japanese Version of the Black Chamber: (the Story of the Naval Secret Chamber) by Toshiyuki Yokoi,

Acknowledgments: I have to thank mr Ken Kotani for answering my questions on WWII Japanese cryptologic history and the staff of the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records for the links to the files in ‘U.S.-Japan Relations, Miscellaneous Diplomatic Correspondence-Special Information File’

Acknowledgments: I have to thank mr Ken Kotani for answering my questions on WWII Japanese cryptologic history and the staff of the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records for the links to the files in ‘U.S.-Japan Relations, Miscellaneous Diplomatic Correspondence-Special Information File’

Dear sir,

ReplyDeleteYour Blog is absolutely fantastic!

Do you any information credible confirmation and reference of the soviet documents intercepted by the Japanese in Harbin related to their plans of a war in Europe (Germany vs Britain and France and in Asia (japan vs US).

This comes from : ynamics of International Relations, by Ernst B. Haas (U. of California [Berkeley]) and Allen S. Whiting (Michigan State U.), ©1956 the McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York.

and a note: These telegrams were intercepted by the Imperial Japanese Government's consul general in Harbin. Japanese copies were examined by A.S. Whiting and accepted as authentic

http://www.richardsorge.com/appendices/dynamics/index.html

Thank you for your help.

Thanks, most of the information presented here is not available anywhere else.

DeleteAbout the Harbin messages, the Soviet diplomatic code in the East was not the unbreakable one time pad but a simpler system. Files from HW 40/29 mention messages from Harbin being decoded by the Japanese in 1944. The file that i‘ve uploaded here says that the ‘break’ into the diplomatic system of Seoul and Dairen was first achieved in 1943. So from my sources I can’t confirm or disprove that the Japanese were reading the Soviet Harbin code in 1940 (or maybe they had a spy inside the Soviet embassy?)

After checking with Ken Kotani it seems that the Japanese had a spy inside the Soviet embassy. Through him they got the codebooks.

DeleteOnly just discovered your blog and am finding them invaluable.

ReplyDeleteOn this topic - do you have any idea what the British R Code and M Cipher were used for?

I'm trying to pin down what codes/ciphers were used by the British Ambassador in Tokyo when communicating with the Foreign Office in 1941. Japanese codebreakers seem to have deciphered at least some of these communications .

The R code and the Government Telegraph code should have been used only for non confidential traffic as they had limited security.

DeleteEnciphered codes such as Cypher M must have been the main diplomatic cryptosystems for confidential messages.

There was also the Inter-departmental Cypher, also used by diplomatic authorities.

Didnt the army have radio operators who broke the japanese code? One being Ralph Hazlett, born 1919, from Brookfield Ohio? I believe I was told he was on B-52's during this time.

ReplyDeleteThe Japanese Army’s enciphered codebooks were harder to solve than those used by the Japanese Navy. The Americans were able to regularly solve this traffic in 1943 after capturing codebooks from the submarine I-1.

DeleteFor more information check the book: ‘The Emperor's Codes: The Breaking of Japan's Secret Ciphers’

did the soviets help the japanese with naval intel during ww2 against the U S ? heard a little about a raid on formosa by the U S being shared with the Japanese.

ReplyDeleteThe messages I posted are from UK national archives HW 40/29 ‘Exploitation of Russian Civil communications by Axis Powers’.

DeleteKotani references HW 40/8 ‘Security of British and Allied communications: periodic reviews (1944 Jan 01 - 1945 Feb 28)’ so there should be more messages in that file. I don’t know the content of those messages. It is possible they have information relevant to your question.

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C11148677

Hi Christos,

ReplyDeleteWhere can I learn more about L-Kikan, or the L Agency? Is there a good source I can go look at?

Thanks,

qz169

It is mentioned in ‘Combined Fleet Decoded’ but I don’t know any other source with more details.

DeleteI wrote about the L-Kikan in parts of this academic paper https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02684527.2022.2123935 and this book https://www.amazon.com/dp/0063310074

DeleteHead of L Kikan, Tsunezo Wachi, had earlier had been commended by Prince Takamatsu for his work intercepting and decoding Chinese codes.

I have more info to come, am awaiting some FBI files that will be declassified soon (I requested and was approved 3 years ago so gotta be soon?)

I have some additional research coming on it