Historians have not only acknowledged these Allied successes

but they’ve probably exaggerated their importance in the actual campaigns of

the war.

Unfortunately the work of the Axis codebreakers hasn’t

received similar attention. As I’ve mentioned in my piece Acknowledging

failures of crypto security all the participants suffered setbacks

from weak/compromised codes and they all had some successes with enemy systems.

Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States did not have

impenetrable codes. In the course of WWII all three suffered setbacks from

their compromised communications.

After having dealt with the United

States and Britain it’s

time to have a look at the Soviet Union and their worst failures.

Move along comrade, nothing to see here

Compromises of communications security are usually difficult

to acknowledge by the countries that suffer them. For example since the 1970’s

countless books have been written about the successes of Bletchley Park, yet

detailed information on the German solution of Allied codes only started to

become available in the 2000’s when TICOM reports and other relevant documents

were released to the public archives by the US and UK authorities.

In Russia the compromise of their codes during WWII has not

yet been officially acknowledged and the archives of the codebreaking

organizations have remained closed to researchers. This is a continuation of

the Soviet policy of secrecy.

The Soviet Union was a secretive society and information was

tightly controlled by the ruling elite. This means that history books avoided

topics that embarrassed the regime and instead presented the officially

sanctioned version of history. Soviet era histories of WWII avoided references

to codes and ciphers and instead talked about ‘radio-electronic combat’ which

dealt with direction finding, traffic analysis and jamming (1).

After the fall of the Soviet Union several important

government archives were opened to researchers and this information has been incorporated

in new books and studies of WWII. However similar advances haven’t taken place

in the fields of signals intelligence and cryptologic history. Unlike the US

and UK that have admitted at least some of their communications security

failures the official line in Russia is that high level Soviet codes were

unbreakable and only unimportant tactical codes could be read by the Germans.

Even new books and studies on cryptology repeat these statements (2).

However various sources such as the TICOM reports, the

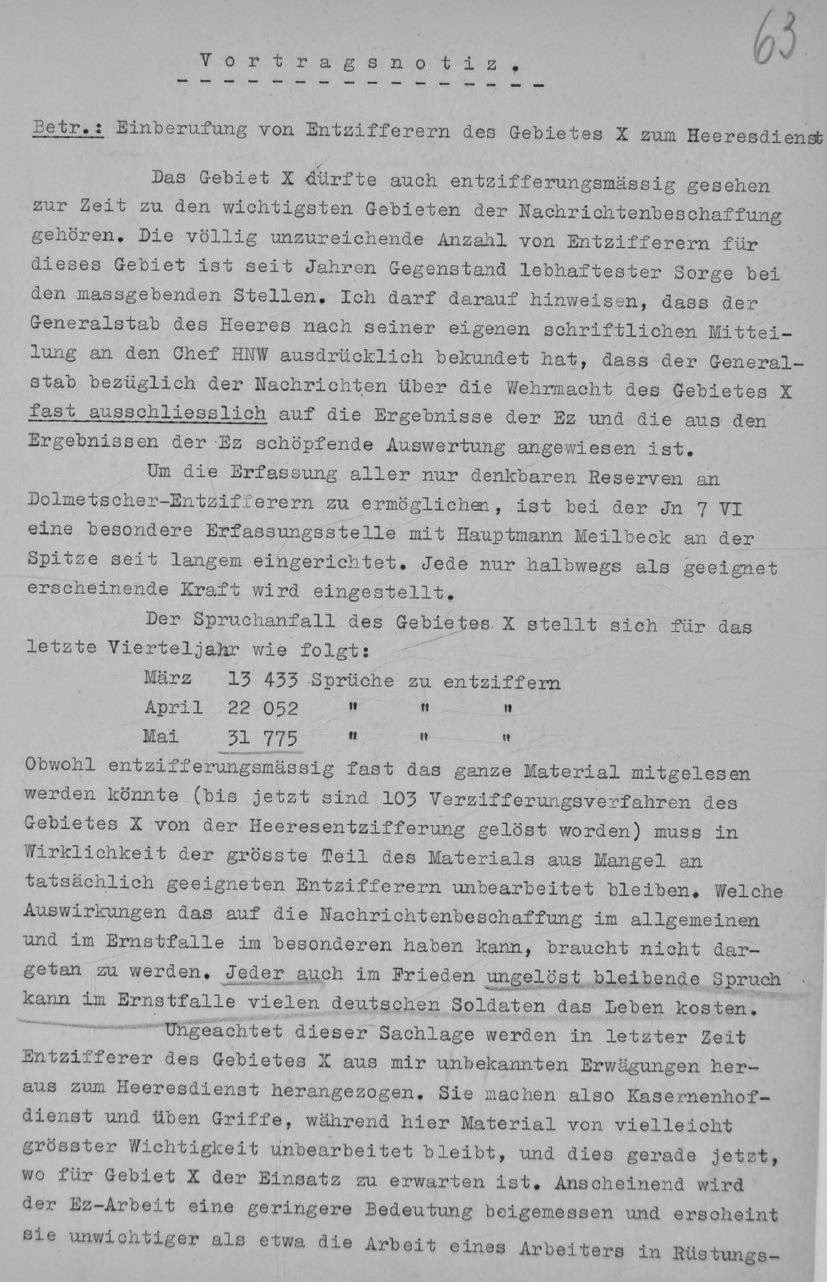

war diary of the German Army’s signal intelligence agency Inspectorate 7/VI and the monthly reports of the cryptanalytic

centre in the East Horchleitstelle Ost

clearly show that the Germans could solve even high level Soviet military and

NKVD codes.

Overview of Soviet

cryptosystems

The secretive Soviet state used various cryptosystems in

order to secure its communications from outsiders. The task of preparing and

evaluating cipher procedures was handled by two main Soviet organizations, the

NKVD’s 5th Department and the Army’s 8th department of

the main intelligence directorate GRU.

In the 1920’s simple substitution systems were used and

these were solved by codebreakers in Poland (Polish-Soviet

war of 1919-21) and in Britain (ARCOS case).

In the 1930’s the communications of units in the Far East were read by the Japanese

codebreakers and during the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-40

Soviet codes were read by the Finns

with disastrous consequences for the Soviet armed forces.

The basic cryptologic systems used by the military, the

diplomatic service and the security services during the period 1941-45 were the

following:

1). The Soviet military used 2, 3, 4 and 5-figure codes

enciphered with substitution methods or with additive sequences. The latter

method was reserved for the most important 4 and 5-figure codes.

2). The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs -

NKVD also relied on figure codes enciphered both with substitution and

addition methods.

3). Partisan

groups used figure codes enciphered with additive sequences or transposed

based on a key word.

4). The diplomatic service had a 4-figure codebook

enciphered with one time pad tables plus an emergency system.

5). The agents of the foreign intelligence service that did

not have diplomatic cover and the Communist International mostly

used a simple letter to figure substitution table to encode a message and this

was further enciphered by using a book and the aforementioned conversion table

to create additive sequences.

6). Internal radio traffic between factories and the People's

Commissariats of heavy industry, tank production, engineering etc was sent both

unenciphered, enciphered with simple cover words or with figure codes and with

one time pad tables.

7). According to the available sources the Soviet Union relied

almost entirely on hand methods for enciphering its important communications. A

small number of cipher machines were available but it doesn’t seem that they

were used widely during the war. The known types were the K-37

‘Crystal’ (Soviet copy of the Hagelin B-211)

and the cipher

teleprinters B-4 and M-100.

8). Voice communications were protected by the EU-2

speech scrambler and the Cobol P device.

Military codes

TICOM reports DF-196 ‘Report

on Russian decryption in the former German Army’, DF-112 ‘Survey of Russian

military systems’, DF-292 ‘The

Cryptologic Service in WWII (German Air Force)’ (4), IF-175 ‘Searbourne

Vol. XIII, PT. 2’, I-120

‘Translation of Homework by Obltn. W. Werther, Company Commander of 7/LN Rgt.

353, written on 12th August 1945 at A.D. I. (K).’ and I-19 a-g ‘Report

on Interrogation of KONA 1 at Revin, France, June 1945’ give a summary of

the main military cryptosystems (3).

The basic systems were 2, 3 and 4 figure letter/word

to figure substitution tables used either unenciphered or enciphered with similar

substitution tables. The 2 and 3 figure code tables were used by frontline

units, while the 4-figure codes were used at division level and above.

Examples of 2 and 3 figure tables (4):

In the period 1939-1942 the codes OKK-5, OKK-6, OKK-7 and OKK-8 were used.

Encipherment was by means of substitution tables.

In mid 1942 the use of the OKK codes was discontinued and instead units were given authorization to create their own 4-figure substitution tables called SUW/SUV. Based on guidelines from the Army’s cipher department each unit had permission to create its own 4-figure code table and the enciphering method.

Examples of SUV tables (6):

For the highest level communications a 5-figure codebook was

used, enciphered with additive tables called ‘Blocknots’. There were two main types of tables, the ‘General’ (31

pages with each page having 300 5-digit groups – each page was valid of 1 day

regardless of the messages sent) and the ‘Individual’ (50 pages with each page

having 60-120 5-digit groups - each additive group could only be used once).

In the period 1939-1945 the following 5-figure codes were

used:

OPTK-35, OK40, K1, 0-11A, 0-23A, 0-45A, 0-62A and 0-91A.

Example of 5-figure code encipherment (7):

The NKVD used procedures similar to the Army’s. At the top

level an enciphered 5-figure code was used. Several large 4-figure codes (up to

10.000 groups) enciphered with additive tables were also used at a high level.

Frontline units used small codebooks (approximately 2.500 values) and code tables

similar to the Army’s. (8)

Example of NKVD code table (9):Partisan codes

The Soviet partisans used various enciphering procedures in

their radio communications with Moscow. These ranged from simple Caesar ciphers

to double transposition, transposition using a stencil and Caesar ciphers enciphered with additive (including one

time pad).

Examples of partisan codes (10):Diplomatic codes

The Soviet diplomatic service used a 4-figure codebook

enciphered with one time pad. In addition there was an emergency cipher

procedure for consulates that did not have access to new enciphering tables.

Foreign intelligence and Comintern codes

Soviet agents operating ‘illegally’ (with no diplomatic

cover) did not have access to a regular supply of enciphering tables so they

had to memorize a simple letter to figure conversion table and use it to encode

their messages. Then they could also use this table for encipherment by using a

prearranged book as a ‘key’ generator. Passages from the book would be taken,

the letters would be converted into numbers through the conversion table and

this numerical sequence would be used to encipher the message (addition without

carrying over the numbers).

The same basic system was used by Communist Parties in their

communications with Moscow. A codebook or conversion table would be used to

encode the message and a random book would provide the additive sequences as

above. (11)

Internal radio traffic

Radio communications between factories, State authorities,

civil aviation and military units in the Soviet interior were sent plaintext,

encoded with a simple system, using 3 or 4 figure substitution codes or with

the Army’s 5-figure code and one time pad tables.

German solution of

Soviet codes in WWII

The German intercept organization in the East

Codebreaking and signals intelligence played a major role in

the German war effort. Army and Luftwaffe units relied on signals intelligence

in order to monitor enemy units and anticipate major actions.

In the period 1941-45 the Army had 3 signal intelligence

regiments (KONA

units) assigned to the three Army groups in the East (KONA 3 for Army Group North, KONA

1 for South and KONA 2 for Centre).

There was also NAA 11 - Signal

Intelligence Battalion, providing intelligence to the German forces in Finland.

This unit exchanged results with the Finnish codebreakers.

In 1942 another KONA unit was added to Eastern front and

from 1943 mostly monitored Partisan traffic, this was KONA 6.

The Luftwaffe had similar units assigned to the 3 Air Fleets

(Luftflotten) providing aerial support to the Army Groups. These were the 1st Battalion of Luftnachrichten Regiment

1 (assigned to Luftflotte 1), Signal Intelligence Battalion East (assigned to

Luftwaffenkommando Ost, later renamed Luftflotte 6) and 3rd Battalion of

Luftnachrichten Regiment 4 (assigned to Luftflotte 4).

Apart from the Army’s Inspectorate 7/VI and the Luftwaffe’s

Chi Stelle several other organizations also worked on Soviet codes. The Navy’s

signal intelligence agency B-Dienst – Beobachtungsdienst had intercept

units in the Black Sea and in the Baltic, the Signal Intelligence Agency of the

Supreme Command of the Armed Forces OKW/Chi

had a Russian department under professor Novopaschenny that worked on the

5-figure code, the Forschungsamt

intercepted traffic from the Soviet interior (mostly of economic content), the

Foreign Ministry's deciphering deparment Pers

Z solved Comintern codes and the Army’s Ordnance, Development and Testing

Group, Signal Branch – Wa Pruef

7 Group IV section C intercepted Soviet multichannel radio-teletype

traffic from inside the Soviet Union.

The Air Signal Battalions (Luftnachrichten Abteilung) were

later subordinated to Air Signal Regiment 353.

Army and Luftwaffe signals intelligence units cooperated

closely and exchanged results on a daily basis.

Both the Army and the Luftwaffe established central

cryptanalytic departments for the Eastern front. The Army’s Horchleitstelle Ost (later renamed Leitstelle der Nachrichtenaufklärung) was

based in East Prussia and worked on Soviet military and NKVD 2, 3, 4 and

5-figure codes. Additional work on the high level 5-figure code was carried out

at Referat 5 of Inspectorate 7/VI, in Berlin.

At the Luftwaffe’s Chi Stele Soviet codes were worked on

by Referat E1, headed by Edwin von Lingen.

The signal intelligence regiments had fixed and mobile intercept units plus a small cryptanalytic centre called NAAS (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal Intelligence Evaluation Center). Although they were subordinate to Horchleitstelle Ost, in practice they had significant autonomy on the traffics they chose to cover (12). The task of the field units was to exploit current enemy cryptosystems using the material given to them by their NAAS units and by HLS Ost. New cipher procedures were not supposed to be handled by forward units but instead they were tackled by HLS Ost and the NAAS units. Important Soviet codes such as the Army’s enciphered 5-figure code and the NKVD cryptosystems were handled solely at HLS Ost and by the central department in Berlin.

The signal intelligence regiments had fixed and mobile intercept units plus a small cryptanalytic centre called NAAS (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal Intelligence Evaluation Center). Although they were subordinate to Horchleitstelle Ost, in practice they had significant autonomy on the traffics they chose to cover (12). The task of the field units was to exploit current enemy cryptosystems using the material given to them by their NAAS units and by HLS Ost. New cipher procedures were not supposed to be handled by forward units but instead they were tackled by HLS Ost and the NAAS units. Important Soviet codes such as the Army’s enciphered 5-figure code and the NKVD cryptosystems were handled solely at HLS Ost and by the central department in Berlin.

The German Allies in the East (Italy, Hungary, Romania) did

only limited work on Soviet codes. The exception to this rule was Finland,

whose codebreaking department had been solving Soviet codes since the 1930’s

and continued to do so up to 1944. Relations between Finnish and German codebreakers

were close and they exchanged information on important systems.

Overview of German codebreaking successes

The communications of the Soviet Union were a major target

of the German codebreakers during the interwar period and several military

systems had been solved up to the 1941 invasion (13). The exploitation of these

codes from an early date allowed the Germans to follow changes and improvements

in Soviet procedures, as simple systems used in the 1920’s and 1930’s were replaced

with more complex ciphers. Also the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-40 served as a training

exercise for the German signal intelligence organizations since ample radio

traffic from actual fighting units could be intercepted and examined. The

occasional mistakes made by Soviet cipher clerks, the large volume of traffic

and the cipher material captured by the Finns and shared with the Germans contributed

to the solution of most of the Soviet enciphered traffic, including the Army’s

high level 5-figure code (14).

In the period 1941-45 the German signal intelligence

agencies continued to exploit a large part of Soviet military and NKVD 2, 3 and

4 figure codes and even succeeded in solving some of the 5-figure traffic.

Limits of available sources

Unfortunately the files of many of the organizations

intercepting and exploiting Soviet codes were either destroyed in WWII or are

still classified by the NSA. However the material released to the US, UK and

German archives in the last decade is sufficient for evaluating the general performance

of German signals intelligence in the Eastern front.

The most reliable sources are the monthly reports of Referat 5 and of Horchleitstelle Ost, which are included in the War Diary of

Inspectorate 7/VI. These are available for the first half of 1941, for the

period 1942-43 but not for January to September 1944 or for the period July

1941 – January 1942 (at least I haven’t been able to find them).

Soviet Army and Airforce codes

The Army’s Inspectorate 7/VI and the Luftwaffe’s Chi Stelle intercepted

and decoded Soviet communications through their forward units and from fixed

stations in the East. Forward units were supposed to exploit systems that had

already been identified and solved. On the other hand new traffic and difficult

high level systems were tackled at the cryptanalytic centre Horchleitstelle Ost/ Leitstelle der Nachrichtenaufklärung

in East Prussia.

This arrangement meant that field units could process a lot

of messages each month without the need for specialized personnel and the results

were quickly communicated to the armed forces. According to TICOM report I-19

(15) the estimated monthly average for KONA 1 (assigned to Army Group South) in

1944 were 5.500 cipher, 6.000 clear text and 500 practice messages for a total

of 12.000. The systems exploited by field units were 2, 3 and 4-figure codes.

The NKVD systems and the Army’s 5-figure code were processed at HLS Ost.

Prior to the 1941 invasion the Luftwaffe’s Chi Stelle could

solve the majority of intercepted Soviet codes (16). The Army agency could also

exploit the majority of systems but it was hampered by lack of personnel and

the processing of the 5-figure code was slow due to the limited number of

messages intercepted daily (17). Still the reports say that the information

from signals intelligence was extremely valuable to the General Staff.

Report of period Jan-Mar 1941:

Report of 10 June 1941:

Report of 16 August 1941:

The files I have do not include the reports of HLS Ost for the second half of 1941 or January 1942 but the report from February shows that the 5-figure code could still be exploited revealing orders for operations, situation reports, reconnaissance reports, information on troop movements, inventory of ammunition and food, reports of desertion etc

Report of HLS Ost - February 1942

Also in 1942 the widely used Army 4-figure codebook OKK was

replaced with a large number of SUV substitution tables. Although the security

of such a system was not very high the use of different SUV tables by each unit

meant that solution depended on the amount of material received and on operator

errors.

In 1943 the reports of HLS Ost show that apart from 2, 3 and

4 figure codes also traffic from the Soviet interior was intercepted and solved.

Report of July 1943

The reports of January-September 1944 are missing but those

of October ’44 - March ’45 show that military codes continued to be solved. The

new 5-figure code 091-A could only

be read in rare cases.

Reports of Referat 2 - October 1944

Soviet Navy codes

The German Navy’s signal intelligence agency B-Dienst monitored the Soviet naval traffic in the

Black Sea, the Baltic and the North Sea. Low level systems used by small ships were continuously read and high

level 4-figures codes could also be exploited till late 1943. An important

success for the German side was the solution of the simple codes used by Soviet

naval aircraft in the North Sea. This traffic carried important information on

the convoys between the UK and the SU. Thanks to this information the Germans were

able to inflict significant losses on these convoys.

NKVD codes

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs - NKVD was a huge organization tasked

with foreign intelligence, internal security, border security, railroad

security and overview of the state run economy. The communications of such an

important organization were targeted by the German codebreakers and traffic

from NKVD border units could be read in the 1930’s (19). During WWII there was a separate department

at Horchleitstelle Ost for NKVD traffic.

NKVD

codes were extensively read, not only 2 and 3-figure codes used by frontline

units but also several large 4-figure codebooks used by higher authorities

(GUP NKVD-General Directorate of Border

and internal security and Front staffs).

By reading these communications the Germans got intelligence

on the operations of the NKVD border units, the conditions in the Army’s rear

areas were the NKVD was responsible for security, intelligence operations,

railway shipments and even reports on the Soviet economy.

The reports of HLS Ost list many NKVD systems solved in

1942, 1943 and 1944. For example in April ’42 5-figure traffic was solved

(since the NKVD also used the army’s 011-A and 023-A codes) and the code N.17 of the 23rd NKVD Railway division.

In June 1942 the codes 06-P

and N.14 are mentioned:

In January the new code 010-P

was solved after discovering the enciphering procedure.

Partisan codes

Partisan codes were investigated by Inspectorate 7/VI’s

Referat 12 (Agents section) in 1942 and by signal intelligence regiment 6 -KONA

6 in the period 1943-44.

The reports of Referat 12 for the second half of 1942 show

that partisan communications were monitored and the different types of traffic

were classified by the cipher system used. However, apart from a few spy cases,

actual traffic was not solved.

List of Russian agents and partisans traffics from October

1942:

In 1943 KONA

6 was assigned to cover partisan traffic and from summer 1943 some of it

could be read. The results were communicated to the security services like the

Abwehr so that enemy agents could be apprehended and partisan operations

thwarted.

Comintern codes

The codes of the Comintern were read by the Foreign

Ministry's deciphering department Pers Z. According to Adolf Paschke (20), head

of the linguistic cryptanalysis department, different books were used in order to

create cipher sequences and encipher the underlying code but thanks to human

error it was possible to solve these and identify the books used. Apparently

the personnel that were responsible for enciphering messages had the tendency

to reuse specific passages from the books thus compromising the whole system.

Paschke said that ‘A particular instance

deserves mention. It concerns telegraphic material of a total length of about

two million digits. In the course of the work of solution it was established

that it had been enciphered by means of five books which gave an encipherment

sequence of about 5 million digits. An apparently hopeless case. And yet

solution was achieved’.

Diplomatic codes

The Soviet diplomatic service used a 4-figure codebook

enciphered with one time pad tables. In the Far East a simpler procedure was

also used, probably due to the lack of new enciphering tables. According to German

accounts they monitored Soviet diplomatic traffic but could not solve messages

due to the use of one time tables.

Internal network

State ministries, factories and military units in the Soviet

interior relied on radio communications for a lot of their traffic because the

landline network was not fully developed to cover the huge areas of the Soviet

Union.

1). Economic traffic between factories was intercepted and

solved by the Forschungsamt (21). According to Paetzel (head of department 6 -

Cipher Research), traffic from the SU averaged several hundred messages per day

and was mostly plaintext with cover words. The chief evaluator Seifert said: ‘Our

greatest success was obtained on Internal

Russian traffic which enabled us to discover the various bottlenecks in the Russian supply

organization’. According to a report on the Forschungsamt some 20-30 multi-channel radio

teletype links were monitored (22).

A British report on the Forschungsamt says that the communications of several Soviet Commissariats (tank industry, munitions, machine tools etc) were read (23):

A British report on the Forschungsamt says that the communications of several Soviet Commissariats (tank industry, munitions, machine tools etc) were read (23):

Internal Soviet radio traffic was also intercepted and

evaluated by the German Army from a base in Staats, Germany (operated by the Army Ordnance, Development and Testing

Group, Signal Branch Group IV C - Wa Pruef 7/IV C ) and by Group VI

(OKH/GdNA Group VI) stationed in Loetzen, East Prussia.

According to the report FMS P-038 ‘German radio

intelligence’ (24):

Strategic

radio intelligence directed against the Russian war production effort provided

a wealth of information for the evaluation of Russia's military potential.

Owing to the general dearth of long-distance telephone and teletype land

circuits, radio communication assumed an especially important role in Russia

not only as an instrument of military leadership but also as the medium of

civilian communication in a widely decentralized economy. In keeping with its

large volume, most of this Russian radio traffic was transmitted by automatic

means, as explained in Appendix 7. The German Army intercepted this traffic

with corresponding automatic equipment and evaluated it at the communication

intelligence control center. Multiplex radioteletype links connected Moscow not

only with the so-called fronts or army groups in the field, but also with the

military district headquarters in Leningrad, Tiflis, Baku, Vladivostock, and in

many other cities. In addition, the radio nets used for inland navigation

provided an abundance of information. Although this mechanically transmitted

traffic offered a higher degree of security against interception, the Russians

used the same cryptosystems as in the field for sending important military

messages over these circuits. The large volume of intercepted material offered

better opportunities for German cryptanalysis. Strategic radio intelligence furnished

information about the activation of new units in the zone of interior,

industrial production reports, requests for materiel and replacements,

complaints originating from and problems arising at the production centers and

administrative agencies in control of the war economy. All this information was

indexed at the communication intelligence control center where reports were

drawn up at regular intervals on the following aspects of the Russian war

production effort:

Planning

and construction of new factories;

Relocation

of armament plants;

Coal

and iron ore production figures;

Raw

material and fuel requirements for industrial plants;

Tank

and gun production figures;

Transportation

facilities and problems;

Railway,

inland shipping, and air communications;

Agricultural

production;

Food

distribution and rationing measures;

Manpower,

labor allocation, and other relevant matters.

Strategic

radio intelligence thus made a slight dent in the Iron Curtain, which during

the war was drawn even more tightly than at present, and offered some insight

into the operation of the most distant Siberian production centers and the

tremendous war potential of that seemingly endless expanse of land.

In the period 1942-45 the analysts of the German Army’s Leitstelle der Nachrichtenaufklärung evaluated this material and issued economic reports based on the intercepted radio traffic (25).

2). The Aeroflot (civil aviation network) 3 figure code was read by Army codebreakers since summer 1943.

This traffic had interesting information on the organization

of Aeroflot, the movement of men and supplies to the front, fuel supplies and the

training of new pilots (26).

3). Apart from standard radio communications there were also multichannel radio teletype devices being used. The Germans were able to intercept these transmissions automatically and print the text. Economic traffic was often sent plaintext while military communications used 3, 4 and 5 figure codes. The 3 and 4 figures could be read.

Cipher machines

At this time there is very limited information on WWII era Soviet

cipher machines.

1). The Germans captured a K-37 machine in the summer of 1941, examined

it and came up with methods of solution. However during the war they did

not intercept any messages enciphered on this device, so it seems that it was

not used in the Western areas of the SU.

2). Apart from the K-37, two

cipher teleprinters were identified by the Germans. Both seem to have had 6

wheels with five enciphering the respective Baudot impulses while the sixth

controlled their movement. The device solved by the Forschungsamt was used on

2-channel networks and had 6 wheels that stepped regularly. During pauses the

device enciphered the Russian letter П seven times in succession and this flaw

was used to solve the device and recover the daily settings (pin arrangement of

the wheels). This success however turned out to be short lived since in late

1943 the Soviet cipher machine was modified and no pure ‘key’ was transmitted

during transmission pauses. It seems that from then on this traffic was only

examined by the Army’s Inspectorate 7/VI (27).

Regarding the second device the war diary of Inspectorate

7/VI shows that the traffic was continuously examined and some progress was

made thanks to operator errors and a flaw in the construction of the machine (28).

This device was used on communications links between Moscow and the Army

Fronts. There were only about 10 links overall with ~8 for the Army and ~2 for

the Airforce (29). Although the machine was not ‘broken’, messages in depth

could be decoded and they contained reports on Soviet and German military

dispositions, , statements by POW's, signal intelligence reports, reports for

TASS and SOVINFORMBUREAU, letters concerning postings, transfers, promotions,

weather situation reports and supply manifests (30).

3). Radio

fax transmissions were intercepted and decoded, however no information is

available on the type of cipher device used on this traffic by the Soviets. The

traffic contained hand-written

communications, typewritten texts, drawings, weather maps, technical diagrams

and charts.

4). Speech

privacy systems were used for radio

telephone conversations

between Moscow and various cities such as Leningrad, Irkutsk, Alma Ata and Chelyabinsk.

The Germans were able to solve the first Soviet device but no information is

available on the traffic they intercepted or its contents. The second device

introduced during the war was more secure and although German specialists

identified it as a Tigerstedt system (time division scrambling) it was not

‘broken’.

Failures of Soviet cipher security

The Soviet Union had failed to secure its sensitive

communications during the 1920’s and 1930’s. In 1920 the victory of the Poles

over the Red Army in the battle of Warsaw

owed a lot to the work of their codebreakers. In the 1930’s Soviet military

codes were read by the Japanese in the East and by the Finns during the Winter war.

In 1941 the sudden German attack destroyed a large part of

the Soviet military and their communications system collapsed. The loss of

trained radio operators and of cipher material meant that Soviet communications

were extensively read by the Germans. Moreover the new hastily trained radio

operators could not avoid making mistakes and thus compromising the security of

otherwise secure systems.

However the widespread use, during the war, of 2, 3 and 4

figure code tables enciphered with substitution methods was a mistake

considering that they could only offer limited security. Especially for the 4-figure

mid and high level communications a more secure procedure should have been

adopted. Obviously the fact that they could be easily used by hastily trained

personnel must have played a role in this case.

Another lost opportunity was the lack of a secure cipher

machine for widespread usage among the armed forces. Such a device would have a

allowed a large volume of traffic to be sent quickly and securely. The Soviets

used cipher machines in very small numbers and only in a handful of

communication links.

Other mistakes noted by the Germans were that the operational

plans of units using secure procedures were compromised by smaller units supporting

them such as artillery, rocket launcher, heavy mortar and engineers since these

did not use secure procedures.

The NKVD was guilty of using insecure codes and also of

keeping their codebooks in use for long periods of time, thus making the work

of the German codebreakers much easier.

The biggest failure of the Soviet cipher departments was their

unwillingness to acknowledge their failures and introduce new secure procedures.

According to Anatoly Klepov (31), in the postwar era there was an evaluation of

Soviet cipher security during WWII and although it was acknowledged that their

codes had been compromised the final report hid this fact in order to protect

the reputation of Lavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD.

This mistake meant that outdated codes and procedures

continued to be used in the immediate postwar period and they were exploited by

Anglo-American codebreakers in the years 1945-48, when they managed to solve

many important Soviet cryptosystems, including the top level cipher

teleprinters.

Conclusion

The use of signals intelligence and codebreaking by the

Germans and Soviets in the Eastern front is a subject that has received very

little attention by historians so far. The main reason was the lack of

adequate sources. The archives of the Soviet codebreaking organizations remain

closed to researchers but in the last decade many important documents on German

signals intelligence operations have been released to the public archives. Conclusion

From these documents it is clear that the Germans invested

significant resources in their signal intelligence agencies and relied on their

output during the fighting in the East. Against an opponent that outnumbered

them in men and war materiel (tanks, planes, artillery) signals intelligence

gave them the opportunity to monitor enemy movements and make efficient use of

their limited resources.

The cryptologic systems used by the Soviet Union at low and

mid level were extensively compromised during the war and in 1941-42 even their

high level 5-figure code could be read. In the period 1943-45 the use of one

time pad in enciphering their 5-figure code secured this system but other

important codes could be read including the systems of the NKVD.

The report FMS P-038 ‘German radio intelligence’ says ‘In the Russian theater the mass of minute

details assembled by German communication intelligence over a period of years

provided a clear, reliable, and almost complete picture of the military

potential, the strategic objectives, and the tactical plans of the most

powerful enemy which the German Army had ever encountered. The results were far

superior to those obtained during World War I’.

Considering the countless enemy cryptosystems solved by the

Germans during the period 1941-45 (military, NKVD, partisan, economic) this

statement does not appear to be an exaggeration.

Notes:

(1). Journal of Contemporary History article: ‘Spies,

Ciphers and 'Zitadelle': Intelligence and the Battle of Kursk, 1943’, 249

(3). DF-112,

pages 129-165, DF-292,

pages 53-86, I-120

‘Translation of Homework by Obltn. W. Werther, Company Commander of 7/LN Rgt.

353, written on 12th August 1945 at A.D. I. (K).’

(4). DF-292, p 54-55 and DF-112, p129-30

(5). DF-112, p151-52

(6). DF-112, p143-44, p153-54

(7). DF-112, p157

(8). Reports of HLS Ost

(9). DF-112, p155-56

(10). DF-112, p158-63

(11). DF-111, p9

(12). DF-112, p115

(13). DF-112, p170-86

(14). IF-175

‘Searbourne Vol. XIII, PT. 2’, p23 and I-120

‘Translation of Homework by Obltn. W. Werther, Company Commander of 7/LN Rgt.

353, written on 12th August 1945 at A.D. I. (K).’, p39-42

(15). I-19b,

p44

(16). DF-292, p24-29

(17). Reports of Referat 5 January-June 1941.

(18). TICOM

I-176, p2 (note that according to TICOM I-120, p39 it was the last 3 digits

that were all odd or all even)

(19). DF-112, p7-22

(20). DF-111, p8-9

(21). TICOM I-25, p2-5

(22). TICOM DF-241 ‘The Forschungsamt’ Part IV, p36

(23). HW 40/186 ‘Activities of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt’

(23). HW 40/186 ‘Activities of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt’

(24). FMS P-038 ‘German radio intelligence’, p123-124

(25). CIA FOIA: Soviet

Union military economic reports - German

(26). TICOM I-116, p2 and TICOM I-173,

p12

(28). TICOM I-153, p3: ‘In Autumn 1944 both the end of

'adder' and every pause in the cipher proper was preceded by seven key letters

[redacted]. Then the traffic went off the air and reappeared in December with

no external change except that the seven ‘residue' letters had been reduced to

three, suggesting a modification of the machine.

(29). TICOM I-153,

p2

(30). TICOM I-169,

p25

very interesting

ReplyDeletegm

The codes of the German Enigma machine were broken by POLISH (not British, or American) cryptologists... The detailed results of their works were passed to the British and French allies in July 1939. On the basis of that the British built their own system they called Ultra.

ReplyDeleteTo clear things up.

ReplyDeleteIn Soviet terms, "radio-electronic combat" specifically means jamming or EW in general, including necessary radio recon and d/f for target-frequency-waveform-azimuth determination.

SIGINT - spectrum monitoring, traffic analysis and d/f, inter alia, for the sake of obtaining intelligence - is called "radio-electronic intelligence" (radioelektronnaya razvedka, RER)

thanks for your many excellent writeups

dck