At the start of WWII, the US armed forces used various means for enciphering their confidential traffic. At the lowest level were hand ciphers. Above that were the M-94 and M-138 strip ciphers and at the top level a small number of highly advanced SIGABA cipher machines.

The Americans used the strip ciphers extensively however

these were not only vulnerable to cryptanalysis but also difficult to use. Obviously a more modern and efficient means

of enciphering was needed.

At that time Swedish inventor Boris Hagelin

was trying to sell his cipher machines to foreign governments. He had already

sold versions of his C-36, C-38 and B-211 cipher machines to European

countries. He had also visited the United States in 1937 and 1939 in order to

promote his C-36 machine and the electric C-38 with a keyboard called BC-38 but

he was not successful (1). The Hagelin C-36

had 5 pin-wheels and the lugs on the drum were fixed in place. Hagelin modified

the device by adding another pin-wheel and making the lugs moveable. This new

machine was called Hagelin C-38 and it was much more secure compared to its

predecessor.

In 1940 he brought to the US two copies of the hand

operated C-38 and the Americans ordered 50 machines for evaluation. Once the

devices were delivered, they underwent testing by the cryptologists of the

Army’s Signal Intelligence Service and after approval it was adopted by the US

armed forces for their midlevel traffic. Overall, more than 140.000 M-209’s

were built for the US forces by the L.C. Smith and Corona Typewriters Company.

(2)

The American version of the Hagelin C-38 was called Converter M-209 by the Army and USAAF and CSP-1500 by the Navy. Compared to the original version it had a few modifications. The M-209 had 27 bars on the drum while the C-38 had 29. Another difference was that the letter slide was fixed. During operation the text was printed by setting the letter spindle on the left to the desired letter and then turning the hand crank on the right.

The M-209 was a medium-level

crypto system used at Division level down to and including battalions

(Division-Regiment-Battalion) (3) and even up to Corps for certain traffic. The

USAAF used it for operational and administrative traffic and the Navy aboard

ships. SIGABA was used for

higher level messages (Army-Corps-Division) and hand systems like Slidex and the

Division Field Code used for tactical messages (Battalion-Company-Platoon).

The Germans called it ‘AM

1’ (Amerikanische Maschine 1)

and the Japanese ‘Z code‘.

Operation of the M-209

The operating principle of Converter M-209 is described in

it’s manual (4):

‘Converter M-209 operates on the crytographic principal

of reciprocal-substitution alphabets. The effect is that of sliding a

normal-alphabet sequence against a reversed normal alphabet. The manner in

which the various elements of the converter shift the alphabets, with respect

to each other, produces a high degree of irregularity in the letter

substitutions during encipherment. For example, in the enciphering of a

message, the alphabets might be arranged in the following manner for the first

letter:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

KJIHGFEDCBAZYXWVUTSRQPONML

Thus, if K were the first letter to be

enciphered, its cipher equivalent would be the letter A. For the second letter

to be enciphered the alphabets might be arranged as follows:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

RQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAZYXWVUTS

If K were also the second letter to be

enciphered, its cipher equivalent would be the letter H. The continual shifting

of the alphabets is the factor which provides security for messages enciphered

with Converter M-209’.

A more detailed description is given by Lasry, Kopal and

Wacker (5):

‘The M-209 functions as a stream cipher, with a pseudo-random displacement sequence generator, and a Beaufort encoder, i.e. a Caesar cipher with an inverted alphabet. The pseudo-random displacement generator consists of two parts: A rotating cage with 27 bars and a set of six wheels. The wheels are non-replaceable, unlike in later Hagelin models. Wheels 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 have 26, 25, 23, 21, 19 and 17 letters, respectively. Next to each letter, there is a pin which can be set to an effective or non-effective state. On each wheel, one of the pins is in the active position, against the bars of the cage. At each step of the encryption or decryption process, all the wheels rotate by exactly one step. Each bar in the cage has two movable lugs. Each lug may be set against any of the six wheels, or set to the neutral position (0), but both lugs may not be set against the same wheel’.

The shifting of the alphabets was achieved through the rotation of the drum by the hand crank. There were 27 bars on the drum, each with two lugs that could be set in active or inactive position.

According to the same article: ‘When the power handle is

pressed, all wheels rotate by one step, thus replacing the 6 pins in the active

position. In addition, the cage performs a full revolution around its 27 bars.

For each bar, if any one of the two lugs was set against a wheel for which the

pin in the active position is in effective state, the bar is engaged and it

moves to the left. The displacement used for encoding the current letter is

equal to the number of bars engaged, and may have a value from 0 to 27. This

displacement is then applied to the current plaintext letter, using a Beaufort

scheme, to form the ciphertext letter, as follows:

CiphertextLetter[i] = (Z - PlaintextLetter[i] +

Displacement[i]) mod 26’

Due to the large number of possible pin and lug

combinations the M-209 had a keyspace of 2174 (6).

The setting up of the device and the construction of keys

and indicators is described in the manual issued with the device. This was the

‘War Department Technical Manual, TM 11-380 Converter M-209’. During the war

three editions were issued in April 1942, September 1943 and March 1944 with

each one superseding the previous one (7). The 1943 and 1944 editions added

more complex rules regarding the selection of lug positions in order to ensure

that the overlap distribution was optimal for the cryptosecurity of the device

(overlap means that the two lugs on a bar are both in effective positions).

Indicator procedure

The machine was set up according to the daily ‘key’. This

specified the internal settings.

There were six rotors that had pins that could be set in active or inactive

position. Then the lug positions on the bars of the drum were set up. Thus,

setting up the daily key consisted of manipulating up to 185 elements of the

device. (8)

The internal settings were changed each day and the external settings were communicated by

means of a complicated

indicator procedure (9).

The operator had to select 6 random starting positions for

the six rotors. Then he would choose a letter of the alphabet at random and

encipher it 12 times. After that he would take these 12 cipher letters and use

them to select new positions for each of the six rotors. Why were 12 letters

needed to set only 6 rotors? Some of the rotors did not have all 26 letters of

the alphabet. When the cipher letter was not available it was crossed out and

the next one used. Then the operator enciphered the message and sent it

together with the external indicator.

Let’s say that we choose to set the 6 rotors at positions

LAREIQ. Then we select the letter J to encipher 12 times. The output is

QPWOINPONMML. Now we set the rotors at the position indicated by this output.

Rotor 1 will be set at Q, rotor 2 at P, rotor 3 cannot be set at W since this rotor does not have this letter. We

discard that letter and move to the next. Next one is O which is available at

rotor 3 so we set it at that. Rotor 4 is set up on I, rotor 5 at N and rotor 6

at P. We will encipher the message with the wheels at positions QPOINP.

The external indicator sent with the message will be the

letter we encoded written twice followed by the initial position of the rotors.

Also, two more letters indicating the cipher

net need to be added at the end. Let’s say that the net for 101st Airborne

division is FK. Then the indicator for the above example would be JJLAREIQFK.

The cipher clerk who receives it will follow the same

instructions to get the real position of the rotors (in our case QPOINP) but

will then set his machine at decipher

to decode the actual message.

These procedures should have made the M-209 very secure

from cryptanalysis, however as with all the other codes and ciphers of WWII it

was human error that allowed the Germans and Japanese to compromise its

security.

Even though the M-209 had impressive theoretical security

(due to its large keyspace) it had the flaw that if two messages were

enciphered on the same initial setting then they could be solved and eventually

the internal settings recovered so that the entire day’s traffic could be

read.

According to William Friedman, chief cryptologist of the US

Army’s SIS, he opposed the introduction of the M-209 because of this weakness

of the device (10):

‘It was about this time that a small mechanical machine

which had been developed and produced in quantity by a Swedish engineer in

Stockholm named Hagelin was brought to the attention of the Chief Signal

Officer of the U.S. Army by a representative of the Hagelin firm. The SIS was

asked to look into it and, as technical director, I turned in an unfavorable

report on the machine for the reason that although its cryptosecurity was

theoretically quite good. it had a low degree of cryptosecurity if improperly used-and

practical experience had taught me that improper use could be expected to occur

with sufficient frequency to jeopardize the security of all messages enciphered

by the same setting of the machine, whether correctly enciphered or not. This

was because the Hagelin machine operates on what is termed the key-generator

principle, so that when two or more messages are enciphered by the same key

stream or portions thereof, solution of those messages is a relatively simple

matter. Such solution permits recovery of the settings of the keying elements

so that the whole stream can be produced and used to solve messages which have

been correctly enciphered by the same key settings, thus making a whole day's

traffic readable by the enemy’.

Exploitation of M-209 traffic by the Axis powers

German exploitation of M-209 traffic

The German signals intelligence organization

Codebreaking and signals intelligence played a major role

in the German war effort. Army and Luftwaffe units relied on signals

intelligence in order to monitor enemy units and anticipate major actions.

The main Army sigint unit was the signal intelligence

regiment - Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung or KONA. The signal

intelligence regiments had fixed and mobile intercept units plus a small

cryptanalytic centre called NAASt (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle -

Signal Intelligence Evaluation Center). (11)

Apart from the KONA units work on Allied codes and ciphers

was carried out at the central cryptanalytic organization of the German Army,

which was Inspectorate 7/VI, in Berlin. The department dealing with US Army

codes was Referat 1, headed by Dr Steinberg. Another important member of the

unit was the mathematician Hans-Peter Luzius. (12)

The Luftwaffe had similar units called Luftnachrichten (Air

Signals) Regiments and Battalions. The central cryptanalytic department was

Referat E, based in Potsdam-Wildpark and their chief cryptanalyst was Ferdinand

Voegele. (13)

Most of the M-209 traffic intercepted by the Germans came

from US Army units so the German Army’s codebreakers were the ones to take the

lead in the solution of the device.

The central cryptanalytic organization Inspectorate 7/VI

had separate departments for the main Allied countries, for cipher security,

cipher research and for mechanical cryptanalysis (14).

US codes and ciphers were worked on by Referat 1, headed by

Dr Steinberg. Originally that department dealt with cipher research but in 1942

it was assigned to US traffic. Additional research on the M-209 was carried out

in Referat 13 (cipher machine research) and data processing and statistical

tests carried out in Referat 9 (mechanical cryptanalysis) which was equipped

with IBM/DEHOMAG punch card

equipment (punchers, verifiers, reproducers, sorters, collators, tabulators including the advanced Dehomag D11

model).

Strength of Referat 1 in 1943 was about 40 men, with some

assigned to forward units. The main systems exploited during the period 1942-45

were the M-94 strip cipher, War Department Telegraph Code 1919, War Department

Telegraph Code 1942, Slidex, DFC - Division Field Code and M-209 machine. Their

results were communicated to field sigint units which also sent back their

solutions and captured material.

The field units working on the M-209 were NAASt 5 and NAASt

7.

NAASt 5 (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal

Intelligence Evaluation Center) based in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France was the cryptanalytic centre of KONA

5 (Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung - Signals Intelligence Regiment)

covering Western Europe. Strength of the unit in 1944 was about 68 people.

NAASt 7 (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal

Intelligence Evaluation Center) was the cryptanalytic centre of KONA 7

(Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung - Signals Intelligence Regiment) covering

Italy.

The NAASt 5 section was headed by sergeant (wachtmeister)

Engelhardt. Under him was a group of young mathematicians. The NAASt 5 unit also cooperated with

Luftwaffe cryptanalysts against the M-209 (15).

Methods of solution

German methods of solution were based on finding messages

that had been enciphered with the same internal

and external settings. These would

have the same external indicator

meaning the starting position of the rotors would be the same for both

messages.

When these messages on the same net with the same external

settings were identified the cryptanalytic attack involved running ‘cribs’

(suspected plaintext in the ciphertext). A ‘crib’ used on these messages was

ZPARENZ (16).

If it was not possible to find messages with the exact same

indicator then there was also the possibility to use messages whose indicator

differed by one or at most two

letters. Another method was to look for messages where the indicators (wheel

positions) differed by one or two letters equally

on all wheels (17).

The German cryptanalysts developed several methods for

identifying if messages were in ‘depth’, regardless of the indicator (18). The

most elaborate method used clear text and cipher text trigram analysis.

The trigram technique is described in TICOM report DF-120

(19) and was similar in concept to Friedman's Index of Coincidence and Turing's

Bamburismus (20):

‘From solved M-209

messages from Africa, out of 10,000 letters the 300 most frequent clear text

trigraphs were counted (taking into account the separator letter "Z’’) and

the clear text intervals of these trigraphs to each other were determined. The differences

found correspond to the negative cipher intervals in messages in depth. The

triple number (Zahlentripel) which arose was weighted with values built up

simply from the product of the frequencies of their occurrences, since the

probability that two definite clear text trigraphs will appear over each other

is equal to the product of the frequency of the percentage of their occurrence.

From

these differences a table was prepared which indicates for us the corresponding

weight for every possible Zahlentripel. One now finds each interval triple

which appears in the two cipher messages, in the upper as well as in the lower

message, and adds up the weights which apply to them. The sum is then

multiplied by 100 and divided by twice the number of positions being

investigated. It is multiplied by 100 in order to get a relationship to 100

positions, and divided by twice the sum of the investigated positions since we

have looked up each position twice - once in the upper and once in the lower

message. For this reason the different sign of the intervals for the clear and

cipher text has no moaning. The final result then gives us a point of departure

for telling whether the messages being investigated are in depth or not.

Experience has shown that values of 50,000 or more make depth probable. Values

under 40,000 speak against depth, and with numbers in between 40,000 and 50,000

one can count on either possibility. Of course, in doing this, scattering

(Streuungen) and coincidences must be taken into account, These things can make

a considerable distortion of the picture, especially in short messages.

Nevertheless, up to now, we have, in general, been able to depend on the

results, particularly In rather long messages.’

Messages were sorted in Referat 9 using punch card

equipment and statistical tests were run on them. The standard IBM/Dehomag

equipment were further modified by the addition of special wiring to enable

them to make the needed calculations.

The punch card machines, due to their design limitations,

were not ideal for making the calculations needed for the solution of Hagelin

type machines, so special cryptanalytic devices were needed. In 1943-44 the

engineer Schüssler was tasked with building such devices but no information is

available on whether they were actually built and used by Inspectorate 7/VI (21).

The field unit NAASt 5 however did use such a device in

1944 in order to find the M-209 absolute settings (22). It seems that the

device worked according to the following principle (23): once two messages in depth had been

identified and solved the relative settings were inputted into the device and a

five letter crib was selected to be tested against the cipher text of another message.

Then the device would test the crib on the cipher text until a positive

solution of the cipher text was reached which caused the device to stop. Then

this setting (which was the absolute one) was checked to see if it could decode

the message.

Information from TICOM interrogations

Dr Steinberg was originally a member of the mathematical

research department of Inspectorate 7/VI and later became head of the USA

section. In Nov 1944 he transferred to the codebreaking department of the Armed

Forces High Command - OKW/Chi where he worked on a Japanese cipher machine.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem that he was interrogated after the war.

His assistant Luzius also became an expert on the M-209.

Luzius was a statistician of the Alliance insurance company before the war. In

1941 he was called up into the Army and posted to Inspectorate 7/VI. There he

worked on cipher machines.

Thankfully we have a short history of the work done on the

M-209 from his report TICOM I-211 ‘Preliminary

interrogation of Dr Hans Peter Luzius of OKH/In 7’, p2

5. The

strip cypher gradually faded out, and was replaced by the M-209 Hagelin at the

beginning of the African campaign. This was a better version of the French

C-36, which had been solved in the early part of the war; he could give no

details as this was before his time. The C-36 had five wheels, whereas the

M-209 had six. Here again, solution was purely analytical, and depended upon

getting two messages with the same indicators, or a mistake in encipherment.

The first break was achieved as the result of a message which was subsequently

re-sent with the same indicators but slightly paraphrased, so that the words in

the text were slid against each other; their task of diagnosis was also made

easier in this case, because, contrary to the instructions which laid down 250

letters as maximum length of a message, this message was over 700 letters long.

They began by guessing a word in the first text, and then trying it out on the

second text, utilizing the fact that the slide between the two cypher letters

would be the same as that between the clear letters. In this way, they could

read the text, and work out the cycle and behavior of the wheels, which enabled

them to derive the relative setting. The solution of the absolute setting,

which would enable them to read the remaining messages on the day's key, was a

more intricate process, and he was unable to recall details, beyond the fact

that it was always possible.

With

practice, they were able to break the relative setting given a minimum of 35

letters of text, although normally they required 60-70 letters. It took them

about two hours to derive the absolute setting, after they had broken the

initial messages.

6. This was the only method of solution known

to them; they could never solve traffic unless they had a depth. The work was

done entirely by hand, except that the indicators were sorted by Hollerith. He

was unable to say what percentages of keys were read, but thought that it might

be about 10%. The only occasion when traffic could be read currently was when

they captured sane keys in advance in Italy, which continued to be used. Them

was a theoretical method of solution an one message given at least 1.000

letters in a message, but this had never occurred and he did not remember the

details.

7. He

was then asked whether they had achieved any other successes with this type of

machine. He recalled that the Hagelin had been used by the Swedes, in a form

known as BC-38. This was similar to the M-209, but with the additional security

feature that, whereas with the American machine in the zero position A = Z, B =

Y, etc., In the Swedish machine the relationship between these alphabets could

be changed. He could not remember whether it had changed daily or for each

message. He himself had worked on this machine and had solved a few messages.

It had been an unimportant sideline, and he could not remember details; he

thought that it had been done by the same method, when two messages occurred

with the same indicators. This had only happened very rarely.

More detailed information is available from primary

sources.

Information from the war diary of Inspectorate

7/VI and the surviving reports of NAASt 5

The complete war diary of Inspectorate 7/VI can be found in

the German Foreign Ministry’s Political Archive, in the TICOM collection. Three

of the five reports of NAASt 5 can be found in the US National Archives, in

collection RG 457 (24).

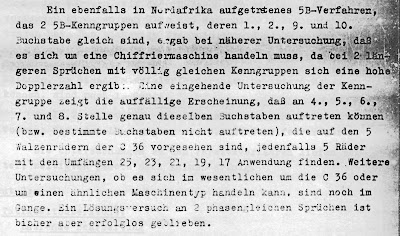

The first mention of M-209 traffic is in the report of

February ’43 which said that messages with two 5-letter indicators where the

1,2 and 9,10 letters are the same was identified as a cipher machine. A

characteristic of the letters 4-8 of the indicator showed that the letters that

could appear were the same as in the wheels of the Hagelin C-36, that is the

wheels had 25,23,21,19,17 positions. There were further investigations into

whether it was essentially the C-36 or a similar type of machine and two messages

in depth were worked on.

Investigations continued in March ’43 however the report

was more pessimistic since it said that ’If the modern, improved Hagelin

devices are used by the Americans, decipherment will only be possible through

special fortunate circumstances’.

The report of April ’43 said that investigations continued

with an effort to clarify if it was a Hagelin type device or another cipher

machine.

A breakthrough came in May ’43 when two messages in depth

were solved and the internal construction of the machine determined (use of the

letter ‘Z’ as word separator was confirmed). The indicator procedure though was

still investigated and it was noted that US troops stationed in Britain had

changed their cipher procedure from the M-94 (called Acr2 by the Germans) to a

machine cipher which was recognized as Hagelin machine type. Messages in depth

from these units could be solved in part and it was attempted to clarify if

this machine was the same as the one used in N.Africa. A BC-38 machine,

borrowed from the Waffenamt (Army Weapons Agency), was modified to decode the

M-209 messages.

The M-209 was also investigated in Referat 13 (cipher

machine research) and their report stated that a method of solution was

developed that however required lots of text. The goal was to further refine

the solution so that it could be applied to short messages.

In June ’43 there was exchange of information with the naval codebreakers since they were also receiving traffic enciphered with the M-209.

Through additional research it was possible to verify that

the Hagelin C-38 was the same machine used by US troops in Britain and in

N.Africa. The indicator system continued to be investigated and there was close

contact with Referat 13 regarding the development of a general solution of the

M-209.

In July ’43 the recent findings and methods regarding the

M-209 were shared with the Navy. There was also a meeting with dr Huettenhain

of OKW/Chi regarding the loan of Hagelin cipher machines (B-211, C-36, C-38).

Captured C-38 were received from Italy, another C-38 was received from the

Waffenamt and one from OKW/Chi.

On 9 July ’43 US and British troops invaded the

island of Sicily and after more than a month of fighting defeated the Axis

forces and captured the island. However, the German forces were able to avoid a

total defeat by retreating in an orderly fashion through the Strait of Messina.

It seems that during the fighting in Sicily the Germans

managed to capture a valid keylist of an M-209 network and thus could read

current US military traffic.

During the month 6 intelligence reports were issued based

on 126 M-209 messages. The captured cipher material allowed the continuous

decryption of the traffic with indicator ‘ID’ and the results were communicated

to KONA 7 (the sigint unit covering Italy). Thanks to the captured material it

was also possible to clarify the indicator procedure. Methods of solution were

further refined and after solving 2-3 messages in depth and finding the

relative settings it was possible to then recover the absolute settings which

enabled the decryption of the entire day’s traffic.

Regarding the M-209 it was stated that without captured

material, messages in depth or other errors regular solution would be

impossible.

In August ’43 there was close contact with the Navy since at Inspectorate 7/VI there were only two serviceable machines while the Navy had a large number available. On 31.8 there was a meeting of dr Steinberg with lieutenant colonel Passow of the Waffenamt in order to discuss the development of special processing devices.

The activity report of Referat 1 said that messages of the

‘ID’ network could be decoded till mid-month and after that it was still

possible (contrary to all expectations) to find several cases of

indicator reuse and thus solve the traffic of those days cryptanalytically and

decode all messages of the net. However, the effort was complicated and

cumbersome and required a large proportion of the staff of the unit. During the

month 8 intelligence reports were issued based on 63 M-209 messages.

Messages in depth were solved during the month and the

absolute settings recovered. This laborious work occupied most of the staff.

Also captured cipher material provided valuable information on cipher

procedures. An original Converter M-209 was captured and together with a

machine sent by the Navy and two machines captured from the Italians and

rebuilt in the workshop deciphering work could be done with a reasonably

sufficient inventory of machines.

In October ’43 dr. Luzius was assigned to KONA 7 to

demonstrate the solution methods for the M-209 but it was confirmed that

processing this traffic would prove too difficult and require too large a staff

for forward units. Exchange of information with the Navy continued with Referat

1 giving them a keylist for the net ‘IF’ and in exchange receiving cipher

material given to the Navy by the Japanese.

Regarding M-209 machines the Navy agreed to give Referat 1

10 electric and 25 hand operated Hagelin C-38 machines captured from the

Italians. These were modified and repaired at the Inspectorate 7/VI workshop

thus satisfying the need for M-209 decoding machines. The acquisition of the

Italian machines ended an effort to purchase 6 new devices from Sweden, thus

saving a considerable amount of foreign currency and preventing any suspicions

that could arise regarding the reasons for the German order.

The activity report said that some messages of the net ‘IF’ could be solved easily due to the captured keylist but the vast majority had to be solved by laborious work (solving messages in depth, recovering the relative settings and then finding the absolute settings).

In November ’43, the head of department was in Berlin from

November 20th to 22nd to bring equipment to the workshop for repairs and to

take repaired equipment with him. He also handed over material for a test

example on the completed device, a small phase detector (Phasensuchgerät), and

to hold preliminary discussions for the construction of further devices with

special leader (Sonderführer) Schüssler. OKW/Chi was urgently interested in

obtaining BC-38 machines and there were discussions with officials from the

Forschungsamt on the C-38. The Forschungsamt made an urgent request to provide

them with such a device so that research could be carried out into the

possibility of breaking into the device.

The activity report said that messages continued to be

decoded and for the first time, it was possible to reconstruct the absolute

setting using a single pair of messages that were in depth, thus avoiding the

laborious process of trying out values for other messages. However, that

method was very time consuming and not always feasible.

The report of Referat 13 said that the results of solving a

longer ciphertext with a known internal machine setting and an unknown

indicator were compiled in a report. Furthermore, the method proposed by the

Navy to solve a longer cipher was investigated theoretically and practically

and judged to be significantly weaker than the methods developed at

Inspectorate 7/VI.

In December ’43 dr Luzius visited NAASt 5 and showed them

the methods of solution of M-209 messages in depth. The activity report said

that the interception of messages in depth was noticeably less frequent than

before and in several cases, despite the existence of messages in depth, no

corresponding solution could be found. The cause of the difficulties that

occurred in these individual cases could not yet be precisely stated.

The 1944-45 reports of Inspectorate 7/VI are not as

detailed as those of the preceding years. However, for 1944 there are also

available 3 reports of NAASt 5.

There are no Inspectorate 7/VI reports for January ’44.

The NAASt 5 report ‘E-Bericht Nr. 1/44 der NAAst 5’

(dated 10.1.44) said that during 1943 the procedure M-94 (ACr2 in German

reports) was being replaced with the M-209. In December ’43 only a few messages

had been deciphered since work on the M-209 only started that month.

The activity report of Referat a2 (as Referat 1 had been

renamed) said that Sergeant Kuhl and two soldiers from the Air Force's

codebreaking department were introduced to the method of determining the

absolute setting of the M-209. There was a notable increase of radio traffic

from US forces in Britain and these contained numerous M-209 messages that

could be solved due to errors in encipherment.

In March ’44 the number of intercepted M-209 continued to

increase and with it the number of cases that could be solved. There were

delays in transmitting this material to Inspectorate 7/VI quickly and an effort

was made to correct this. On February 26th, the cryptanalysts of NAASt 5

managed for the first time to recover the setting from two messages in depth

and to decipher the associated daily material.

The NAASt 5 report ‘E-Bericht Nr. 2/44 der NAAst 5’ (dated 1.4.44) also mentions the increase in M-209 traffic and said that from the last two letters on the indicator (identifying the network and keylist used) it was seen that in Britain two networks made up most of the traffic. Four to seven different networks appeared every day on average. Occasionally, even the bigram of the previous day was used. Solved M-209 messages were also used to break into the US callsign book which turned out to be identical to the one used in Italy.

In April ’44 the Referat a2 report said that the intercepted material remained at the previous month’s level.

In May ’44 the M-209 messages continued to be intercepted

in large numbers (12.600 according to the report) and frequent cases of two or

more messages with the same indicator led to the solution of several days

traffic.

On 6 June 1944, the Western Allies invaded

France and gained a foothold over the Normandy area. The German forces in

the West reenforced their units in Normandy and were initially able to block

the Allied advance for two months. After hard fighting the Allies were able to

breakout from the Normandy area in August and they quickly moved to liberate

occupied France.

Prior to the invasion the German signal intelligence

agencies tried to gather as much information as possible on the location and

movement of Allied units in the UK in order to find out where the landings

would come.

From the war diary of Inspectorate 7/VI and the reports of

NAASt 5 it is clear that in the first half of 1944 M-209 messages from US

forces in the UK were solved and valuable intelligence was gathered on the

groupings of US military forces.

In the period February-May ’44 the USA section of

Inspectorate 7/VI issued 47 reports based on 678 decoded messages. Also, the

report ‘E-Bericht Nr. 3/44 der NAASt 5’ (Berichtszeit 1.4-30.6.44) shows that NAASt 5 solved 1.119

messages during April-May ’44 and got intelligence on the assembly of US

troops. The same report also mentions the reconstruction of the US callsign

book and the preparation of a report on the M-209 titled ‘Über eine Methode

zur vorausscheidung der Konstanten C26 und C25 bei der absoluten Einstellung

der AM1'.

Activity report before the invasion

…………………………………………

1). AM1:

Focused on decoding the AM1. Ten absolute

settings were recovered, which brought the deciphering of 1,119 messages. This

cipher-material, mostly composed by the U.S American Expeditionary Corps, gave valuable

insights into the location of enemy groups.

After the Allies landed in Normandy M-209 messages continued to be read revealing the Allied order of battle. The messages for the days of 6-9 June were solved thanks to captured cipher material and these revealed the presence of an Army, a Corps and five divisions, brigades and battalions (eine Armee, ein Korps, 5 Divisionen, Brigaden und Bataillone). During the month 134 advance reports were issued (S-Meldungen/Sofortmeldungen) based on 2.157 processed messages (many intercepted in May and solved in June).

The June ’44 report of Referat a2 said that a number of M-209 messages were solved. During the month 22 advance reports were issued based on 318 messages.

In July ’44 there was increased cooperation with the Navy

and Airforce on the M-209. The solution of daily keys led to the issuing of 26

advance reports with 586 messages. By using teleprinter links the processing

and evaluation of the results was accelerated. Also, valuable captured cipher

material arrived from Normandy.

In August ’44 21 advance reports were issued based on 269

messages. The personnel of NAASt 5 were able to solve important M-209 messages

thanks to captured material. However, due to the deterioration of the German

front the unit was moved to the east and this led to a fall in the number of

messages and teleprinter traffic sent from the unit in the second half of the

month. The report also says that processing of the M-209 was handed over to

Referat b2 (cipher machine research) with simultaneous transfer of 5 clerks to

b2.

In September ’44 messages with the same indicator were

regularly transmitted by KONA 7 but due to the problematic teleprinter

connection this was not true for KONA 5. The report of Referat b2 said that a

number of relative and absolute settings of the M-209 had been solved.

In October ’44 there was another reorganization of the

department and the reports on US systems appear under Referat 3a. The report

said that there was a decrease in intercepted material. Solution of messages

continued, some thanks to captured material and some thanks to solved keys

provided by Referat 1b. The report of Referat 1b said that it was possible to

recover a number of relative and absolute settings of the American, French, and

Swedish C-38.

In November ’44 Referat 3a worked of the traffic not solved

by the KONA units and the report of Referat 1b said that 9 settings for the

M-209 had been solved.

In December ’44 there was a meeting with Voegele, chief

cryptanalyst of the Luftwaffe codebreaking department in order to discuss the

systems used by the Western Allies. The unit continued to work on traffic not

solved by the KONA units. The report of Referat 1b said 5 relative and absolute

settings were solved for the M-209. In addition, a Swedish C-38 key could be

determined.

After the German defeat in Normandy their forces had retreated back to the German border. There they consolidated and reenforced their units in order to use them for a counterattack that would inflict such a defeat on the Western Allies that it would alter the direction of the war.

The German units used landlines and couriers

in order to maintain secrecy and they succeeded since their attack on December

16 caught the Allies by surprise. This was called the Battle of the Bulge

and battles continued till January 28. Eventually, the Allied material

superiority defeated this last German offensive operation in the West but their

initial successes alarmed the Allies and led to heavy losses for the US

troops.

It seems that in their planning and the offensive

operations they were greatly assisted by signals intelligence, especially the

exploitation of US radio traffic. The British became aware of the extent of the

German success thanks to decoded German messages. These messages revealed the

exploitation of reused M-209 keys, plain-language signals giving the results of

prisoner interrogations and M-209 messages divulging a wide array of

intelligence about troop dispositions, proposed movements, reconnaissance activity

and more. For example (25):

Their assessment, contained in the report 'Indications of the German Offensive of December 1944' was that 'It is a little startling to find that the Germans had a better knowledge of U.S. Order of Battle from their Signals Intelligence than we had of German Order of Battle from Source' (26).

In January ’45 the reports on US systems appear under

Referat 2a. Regarding the M-209 there was processing of messages in depth. The

report of Referat 1b said there were 6 relative and 10 absolute solutions of

the US M-209, 2 solutions for the French M-209, and 3 solutions for the Swedish

C-38.

In February ’45 processing of the M-209 was completely taken over Referat 1b. The report of the unit said that in collaboration with the group of Engelhardt at NAASt 5 eight machine settings of the AM 1 were solved and the associated daily traffic read.

The last report of March ’45 said a number of settings of

the M-209 could be solved in cooperation with the Engelhardt group.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to locate the two NAASt

5 reports E-Bericht 4/44 der NAAst 5 (Berichtszeit 1.7-30.9.44) dated

10.10.44 and E-Bericht der NAAst 5 (Berichtszeit

1.10.44-30.12.44) dated 14.1.45. However interesting information about the

work of the unit during that period can be found in the interview of Reinold

Weber, a distinguished member of the unit (27).

Reinold Weber and the German ‘bombe’

An interesting overview of events regarding the NAASt 5

unit is given by one of the cryptanalysts who served there named Reinold Weber.

According to an article at Telepolis magazine (28),

Reinold Weber was born in Austria in 1920 and in April 1941 he was drafted to

the German army and assigned to a signals company in the Eastern front. In

December ‘42 he was transferred to an interpreter school because he had good

knowledge of English (his family lived in the US during the years 1930-36)

and while stationed there, he took an intelligence test and scored third. His

good results got him reassigned to the signal intelligence service and in

January ’43 he was sent to Berlin for a six-month course in cryptology. There

he did not distinguish himself but he was able to complete the course in August

’43 and in the following month he was sent to NAASt 5 in Louveciennes, near

Paris.

Although Weber was a newcomer, he quickly gained the

respect of the other codebreakers by solving messages enciphered with the so

called ‘TELWA’ code. This system was called TELWA because that was the

indicator at the start of these messages. (Its original designation was ‘US

War Department Telegraph Code 1942 - SIGARM’ and it was used

extensively in the period 1943-45).

Weber’s statement can be confirmed from the report

‘E-Bericht Nr. 1/44 der NAAst 5’, p15-6 which said:

‘In August and September the TELWA 5-Letter code was

recognized as systematic. We managed to find the formula and the related size

of about 125.000 possible code groups of which 25.000 groups could be excluded

through graphical and statistical ways by using the formula. Hence the code

group construction and the size was known. Now it was possible due to the

available material to start the interpretation of the code assignments. It was

assumed that the code was alphabetic and that the message content corresponded

to the AC 1 usage. The first break-ins and confirmations were achieved

simultaneously with FNASt. 9. Already in mid-November was it possible to solve

some of the messages because of the available material’.

At the end of 1943, Weber was transferred

from Paris to Euskirchen, near Cologne to work on the TELWA code. This was the

location of Feste 3 (Feste Nachrichten Aufklärungsstelle/Stationary Intercept

Company). This unit intercepted radio traffic from the US interior both morse

and radio teleprinter, including the 6-unit IBM

Radiotype traffic (for more information

check the essay ‘Army

Command and Administrative Network, IBM Radiotype and APO numbers’).

In April ’44 Weber returned to NAASt 5, which

had now moved to Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The unit was working on the M-209

cipher machine which was in widespread use among the US military units. The

settings were solved sometimes several times a week and sometimes only once in

14 days. The absolute settings were worked out by a small group and Weber was

able to join them. It seems that the spelling of numbers in the M-209 was

exploited as a ‘crib’. (Note that in TICOM report I-113 the cryptanalysts

mentioned were Schlemmer, Engelhardt (a mathematician), Rathgeber (ex-chemist)

and Flick, Thuner, Dato)

According to Weber some of the decoded

messages contained information on upcoming bombing operations against German

cities and this information was passed on to higher authorities.

The cryptanalytic device

In April ’44 Weber had thought about using a cryptanalytic

device to speed up the solution of the M-209. When he shared his idea with his

superiors he was sent to Berlin to discuss it with experts from OKH (Army High

Command) (probably meant Inspectorate 7/VI) and they directed him to the

Hollerith punch card company (probably meant DEHOMAG). However, the

response he got from the company was that it would take two years to build such

a device.

Weber returned empty handed but did not forget his idea to

build the electromechanical cryptanalytic device. In August ’44 the collapse of

the front and the retreat of the German Army in France led to the move of NAASt

5 from Saint-Germain to Krofdorf, near Giessen in

Germany. In Krofdorf there was a precision engineering company called Dönges

whose machine tools were used by Weber and his coworkers in order to build his cryptanalytic

device. According to Weber by mid-September the device was ready and it was

used to recover the daily settings of the M-209 in 7 hours. The message

contained details of a bombing operation scheduled for several weeks’ time.

The unit continued to work on the M-209 till early 1945

when advancing US forces led to another relocation of the unit, this time to Bad Reichenhall in Bavaria. Some members of the unit

abandoned their posts but Weber made it to Bad Reichenhall and then to Salzburg

and was surprised to see that his device had also been transported there

in one piece. Unfortunately, the operations of the signal intelligence service

had deteriorated so much that there was no interception of M-209 messages to

work on. For this reason, his superiors ordered that the device was to be

destroyed so it was broken up with hammers.

Weber’s story appeared in 2004

but until recently it could not be independently confirmed. Thankfully the

TICOM report DF-114 ‘German Cryptanalytic device

for solution of M-209 traffic’ has the blueprints of this device (released

by the NSA to NARA in 2011

and uploaded to Scribd

and Google drive by me in 2012).

This proves that the Allies were not the only ones to build specialized cryptanalytic equipment for the solution of cipher machines. The Germans also had their own ‘bombe’.

M-209 traffic from the USAAF and US Navy

Regarding the solution of M-209 messages of the USAAF and

US Navy there is limited information available:

USAAF M-209:

The M-209 was also attacked by the codebreakers of the

Luftwaffe. The central department OKL/Gen

Na Fue/III (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe/General Nachrichten

Fuehrer/Abteilung III) cooperated with the Army’s signal intelligence agency.

Voegele who was the chief cryptanalyst of the Luftwaffe

gave some information in TICOM report I-112 and Seabourne report vol XIII:

From I-112 ‘Preliminary

Interrogation of Reg. Rat Dr Ferdinand Voegele (Chi Stelle, Ob.d.L.) and Major

Ferdinand Feichtner (O.C. of LN Regt. 352)’, p4

4. (g)

U.S. Hagelin Machine (M. 209)

The

first success was achieved in March or April, 1944, On the western Front the

keys were broken for 6 to 8 days per month but in the Mediterranean cypher

discipline was much stronger and keys were broken on only one or two days per

month.

A key

chart was captured in September or October, 1944. Although in theory 22 hours

should suffice for breaking, the time lag was 8 to 10 days in practice, owing

to delays in the reception of raw material.

The breaking of M.209 was soon left to the Army who

intercepted most of the traffic.

Hagelin traffic was considered of little value as compared with Slidex which

was read in bulk. Lt. Zimmerlin (a French prisoner at Tuttlingen) and Sgt. von

Metzen were M.209 specialists.

In another part of the report Voegele says there was

collaboration with NAASt 5 and

exchange of indicators with OKH and OKM.

Also, from Seabourne report vol XIII ‘Cryptanalysis’, p12:

‘Toward the end of the year, M-209 messages on MAAF (Mediterranean Allied

Air Forces) networks were deciphered more frequently. In October 1944, it was

possible to decipher the entire traffic of a network in the West for four weeks

by virtue of a captured list of M-209 settings’.

Lieutenant Ludwig, chief evaluator on the Western front,

gave interesting information in TICOM report I-109:

From I-109 ‘Translation

of a Report by Lt. Ludwig of Chi Stelle OB.d.L, based on questions set for him

at ADI(K)’, p37

A.

M-209 (Small cipher machine).

German

name for system: AM1 (American 1). The cipher system appeared in American army

and air force networks below Army Corps or Command.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Work

on the system was done simultaneously in section E at Potsdam-Wildpark and

Sigint interpretation station 5 (NAAST 5) at St. Germain. As far as I remember

the first messages were decoded in February, 1944, by NAAST 5. They originated

from the ground networks of VIII Fighter Command (65th, 66th and 67th wing) and

contained statements of an administrative nature, but also tactical

indications, such as the change over to Mustangs etc.

The

original of every message was sent to Potsdam, one copy to the Army. The army

got better results. Because of those

results the interception of such messages was stepped up considerably, from

about 50-200-300 messages a day, with priority over other tasks. On the

invasion starting, the GAF cryptanalytic section too was finally moved from

Potsdam to Paris (14/3 formerly W control 3) and close co-operation in

cryptanalytical work was established with the army. After the start of the

invasion some interesting messages about the losses of the 101st Airborne

Division were decoded; apart from that the decoded messages were of greater

value to the Army than to the GAF. Cryptanalysis was, as far as I remember,

made more difficult later by the fact that the individual service groups

(armies, commands) no longer used the same cipher setting, so that they had to

be worked out separately. As far as the GAF was concerned, therefore, each

individual command was monitored and worked on in turn with all available

resources. Good results were achieved in the case of IX Air Defense Command

(details of A.A. units) and the IX Eng. Command (extension of airfields, effect

of the V 1 bombardment on Liege airfield). The monitoring of the networks of

the Tactical Air Commands also brought results: e, g. the forming of the XXIX

Tactical Air Command became known from a decoded message.

US Navy M-209:

The US Navy also used the M-209 but according to the

British report HW 40/7 (29) the

codebreakers of the Naval agency B-Dienst only managed to read a few days

traffic. This was due to the better use of the M-209 by the US Navy compared to

the Army. Specifically, the Navy used indicators enciphered on bigram

substitution tables (30).

Misuse of the M-209:

Although the M-209 was generally supposed to be used up to

division level some of the messages the Germans decoded were from higher levels

of command like Corps and some were USAAF messages containing details of

upcoming bombing operations.

In these cases, the M-209 was used for messages that should

probably have been passed on the SIGABA cipher machine. Perhaps the limited

number of secure cipher machines forced commanders to resort to the use of less

secure methods.

The Japanese effort to solve the M-209 machine

The Japanese codebreaking agencies

Imperial Japan entered WWII with three separate

codebreaking agencies under the control of the Army, Navy and Foreign Ministry.

Details of their successes against enemy codes have been hard to find because

after Japan’s surrender, in September 1945, they had time to destroy their

records and disperse their personnel.

Still the few remaining documents in Japan combined with

decoded Japanese messages found in the US and British archives can provide a

basis for assessing their operations during the war.

The Japanese Army’s codebreaking department focused on the

codes of the US, Britain, China and the Soviet Union (31). Regarding US codes

they read low level Army and USAAF systems and in late 1944 they were able to

exploit M-209 traffic from US divisions.

The Z code and the Japanese Army’s mathematical

research department

In 1943/44 the Japanese authorities started recruiting

University graduates and mathematicians in order to scientifically attack the

more difficult Allied cipher procedures (32). Information on the solution of

the M-209 is available from the mathematician Setsuo Fukutomi, a member of the

unit (33):

‘These M209 encoding-machines were in general use at the

front divisions of the American armed forces. The General Staff of the Japanese

Army had bought a prototype of this machine in Sweden before the war. The

military engineer Yamamoto mentioned above guessed that “M209” was an

adaptation of this Swedish prototype. He could even determine the details of

the modifications of the prototype that had produced M209. At that time, I was

serving as a soldier working at the General Staff. I noticed that the keys of

the codes of the M209 were so-called “double keys”, and I succeeded in breaking

these double-keys. After that, a team including a number of drafted officers

including myself were sent to the Philippines. We managed to obtain some good

decoding results, but the way the Americans made the daily change of coding

keys was such that we were unable to break their codes every day, which

strongly restricted the benefits we earned from our work’.

It seems that the Japanese military attaché in Sweden,

General Onodera Makoto was able to acquire Hagelin C-38 machines which were

then transported to Japan for analysis (34).

The Japanese called the Converter M-209 ‘Z code’ (35)

(since Z was used a word separator) and according to US sources probably

acquired cipher material during the battle of Saipan in June-July 1944 (36).

Then they used this material in order to find a general solution of the device.

Their method of solution was described in a report titled ‘The report on the

Construction and Solution of the Z code’ (37).

Unfortunately, there is no detailed information on their

wartime effort to solve M-209 traffic.

Conclusion:

The M-209 cipher machine was used extensively by the US

armed forces in the period 1943-45. In theory it was a secure device however in

practice the many mistakes made by operators enabled the German and Japanese

signal intelligence agencies to exploit this traffic.

German codebreakers were able to exploit this system,

especially Army traffic. By reading the messages they got tactical information

and were able to identify units and build the enemy order of battle. At times

the M-209 was used for high level traffic and details of future operations

became known to the Germans.

The decoded M-209 traffic was particularly important for

the Germans during the invasion of Sicily, invasion of Normandy and the Battle

of the Bulge.

Work was carried out both in Berlin by the central

department of the German Army’s signal intelligence agency and also from

forward units in France and Italy. Initially only the central department could

recover the internal settings but eventually the forward units also developed

this capability and contributed significantly to the solution of M-209 traffic.

The use of a specialized cryptanalytic machine by the

Germans was a noteworthy engineering achievement. Also, their trigram technique

for identifying depths was similar to advanced statistical methods developed by

the Anglo-American codebreakers for cipher machine analysis.

Overall, the solution of the M-209 was an important success

for the German side. In 1943-45 the M-209 together with Slidex and the War

Department Telegraph Code 1942 were the main sources of information for the

German codebreakers in the Western European theatre.

In the Pacific theatre the Japanese Army’s codebreakers

were able to solve US Army traffic and their success might have played an

important role during the battles of 1944/45 (Saipan, Philippines etc).

Unfortunately, not many details are known about their work.

In the end an accurate assessment of the value of the M-209

was given by William Friedman in a postwar study (38): ‘It turned out that

under field conditions the fears upon which I had based my personal rejection

of the Hagelin machine proved to be fully justified— a great deal of traffic in

it was solved by the Germans, Italians, and Japanese. If I was chagrined or suffered

any remorse when I learned about the enemy successful attacks on M-209 traffic,

those feelings were generated by my sense of having failed myself to think up

something better than the M-209 despite the shortsighted attitude of the

military director of the SCL’.

The M-209 might not have been unbreakable but compared to

the possible alternatives (systems like Playfair, enciphered codebooks,

Cysquare, double transposition or the M-94 and M-138 strip ciphers) it was the

superior system.

The hand systems were either weaker cryptologically or they

were too cumbersome to use in the field. Moreover, their adoption would require

the constant production and distribution of large volumes of cipher material to

units across the globe. The M-209 on the other hand, once distributed, only

needed a keylist and this could be created not only by a central authority but

also by signal officers in the field, using the instructions contained in the

TM 11-380 manual.

M-209 Simulators

For those of you who want to actually use the M-209 check this simulator by Virtual Colossus and the one by Dirk Rijmenants.

Additional information:

1). Hagelin BC-38 for the Office of Strategic Services

Prior to the US entry into WWII the country lacked a

unified intelligence agency. Intelligence was collected by several

organizations such as the Army’s Military Intelligence Service, the Navy’s Office

of Naval Intelligence and by the State Department. For this reason, the Office

of the Coordinator of Information was created in 1941 and in 1942 its foreign

intelligence functions were transferred into the newly established Office of

Strategic Services. The OSS was responsible for collecting foreign

intelligence through spies, performing acts of sabotage, waging propaganda war,

organizing and coordinating anti-Nazi resistance groups in Europe, and

providing military training for anti-Japanese guerrilla movements in Asia.

In 1942 the Communications Branch of the OSS acquired a

small number of electrically powered Hagelin BC-38

machines that were equipped with a keyboard. These were designated BC-543 and

they were used by OSS stations. The machines were manufactured in Sweden,

transported to the US and serviced at a house in Greenwich, Connecticut that

Hagelin bought for this purpose (39).

Initially the internal settings and the indicators were

prepared by the Signal Intelligence Agency (40) but it seems that by 1943 the

OSS personnel were responsible for the production of keylists and the SIS only

provided the indicators (41). The BC-543 machines were probably not used

throughout the war, as they are not mentioned in the OSS cryptographic plan for

1945 (42).

2). Boris Hagelin the millionaire

Boris Hagelin became the first crypto millionaire thanks to

the sale of the M-209 machine to the US government. The report ‘H.R.

1152-Friedman Relief Bill and Related Informal Notes’ (43) says that after

taxes he kept approximately 1.850.000 dollars!

3). The Hagelin patents

The patents that Hagelin transferred to the US government

were 2,089,603 and 2,247,170. They can be downloaded from the US Patent

and Trademark Office.

4). Postwar use:

The M-209 was used by the US military during the Korean war of 1950-53. Did

the same security compromises also occur in that conflict? At this time there

is no information on whether M-209 traffic was exploited by a foreign power but

it seems reasonable to assume that the Soviet codebreakers would have been able

to solve messages in depth and recover the absolute settings.

5). The special conference on M-209 security

During the war the British were aware from decoded messages

that the regular solution of M-209 traffic by the Germans gave them valuable

intelligence regarding the US order of battle and their operational plans. It

seems that after the war they examined the files of Inspectorate 7/VI, which

had been found in 1947 in a camp in Austria, and they must have considered the

solution of the M-209 as a very serious breach of Allied cryptosecurity. The

Americans were obviously interested in downplaying this compromise but in

October 1950 a conference was held in the US with American and British

officials to discuss the matter (44).

William Friedman said: ‘that the purpose of the

gathering was to discuss in general the security of the American cipher machine

M-209, and in particular the amount of M-209 traffic solved by the Germans

during World War II and the amount of intelligence they obtained therefrom. Mr.

Friedman said that the question had arisen during a recent discussion in which

the British representative, Mr. Miller, had referred to the vast amount of

intelligence which had been obtained by the Germans from the reading of traffic

encrypted with the American cipher machine M-209, a statement the validity of

which Mr. Friedman had questioned and which he had asked Mr. Miller to discuss

with him’. The Americans tried to downplay the extent of the M-209

compromise but in the end, it was accepted that ‘Disregarding information

obtained from the use of captured M-209 key lists, it is generally agreed that

a considerable amount of American M-209 traffic was broken by the Germans

during World War II, from which little tactical intelligence was deduced, but

from which an appreciable amount of strategic intelligence was obtained. It is

further agreed that, due to the inefficiency of the German intercept

organization, the lack of modern cryptanalytic machinery, and the failure of

the Germans at high levels to appreciate the value of speedy intercept,

forwarding, and processing of traffic, the German success did not represent the

maximum potential exploitation’.

As can be seen from the reports of Inspectorate 7/VI and

NAASt 5 this is not an accurate assessment of the German effort and the

statements made during the conference are contradicted by the German reports

(speed of M-209 solutions, number of M-209 keys in use, use of cryptanalytic

machine, use of teleprinter lines for transmission of traffic).

A more accurate assessment would be that within six months

of intercepting M-209 traffic the Germans had managed to identify the

cryptosystem, solve messages in depth, analyze the internal operation of the

device and clarify the indicator procedure. By 1944 the interception of M-209

traffic was given a high priority both by the Army and Air Force, the field

sigint units had been shown the methods of solution and could contribute to the

recovery of relative and absolute settings, traffic and indicators were transmitted

through teleprinter links and even a specialized cryptanalytic device was used.

Considering the deterioration of the German economy and military organizations

in the period 1943-45 as well as the constant retreats of German troops this

effort was close to the best that could be accomplished under the

circumstances.

6). M-209 vs equivalent British ciphers

In the previously mentioned M-209 security conference the

British representative mr Perrin stated that their equivalent system the Stencil

Subtractor (SS) Frame, ‘was never read by the Germans except for one

month when the basic book had been captured’. This implies that the system

was superior to the M-209 and that in general the British had a very high level

of cryptologic security during the war.

The reality was different. The British high level

enciphered 4-figure codebooks were read by the Germans during the war.

Specifically, the Royal Navy’s Code

and Cipher, the Army’s War

Office Cipher, the RAF’s

Cipher and the Interdepartmental

Cipher (used by the Foreign Office, Colonial, Dominions and India offices

and the Services).

Regarding midlevel ciphers a report from October 1942 says

that the authorized systems were Cysquare and enciphered three figure codebooks

(45).

The enciphered three figure codes were not only inferior to the M-209 cryptologically but they also required the creation, printing and distribution of codebooks and enciphering tables to field units.

As for Cysquare,

it was a raster type cipher with a high level of theoretical security but

according to its creator John Tiltman it proved to be a failure in the field (46):

‘At this point I may as well confess that the cipher was a complete flop. It

must have been issued to the Eighth Army in pad form as it was apparent very

shortly after its introduction that the code clerks refused to use it on the

grounds that after a very little desert weather and use of indiarubber the

permitted squares were indistinguishable from the forbidden ones’.

Mr Perrin compared the M-209 to the Stencil

Subtractor Frame, so it seems that at some point the standard British

midlevel cryptosystem became the codebook enciphered with the SS Frame. The SS

Frame was a stencil that was used together with a daily changing numerical

table. The SS Frame defeated ‘depths’ as the user could select different

starting points for the enciphering sequence and that point was further

enciphered. This system might have had a high level of theoretical security but

it was inferior to the M-209 in speed of encipherment/decipherment and significant

resources had to be invested into creating, printing and distributing all this

cipher material over long distances. Moreover, the loss of a codebook could

compromise all the traffic sent in that system (as mentioned by mr Perrin)

while capturing a M-209 keylist only compromised that day’s traffic.

For the sake of completeness, the M-209 should also be

compared to the British double transposition cipher (with different keys for

each stage). In November 1943 double transposition was adopted as the standard

Low Grade Cipher, to be used together with the Map Reference code and Slidex (47).

Double transposition, with different keys for each cage was a very secure

system, provided however that it was used properly. It seems that this system

was not a success because it was too complex to use in the field and the

soldiers simply sent their messages in the clear. The War Office report

announcing its replacement in February 1945 said (48):

‘Sir, I am commanded by the Arny Council to inform you

that further consideration has been given to the suitability for operational

purposes or the Low Grade cipher 'Double Transposition" which was

introduced for use throughout the Army by War Office letter 32/Tels/943 dated

5th November, 1943.

2. Experience shows that while this cipher

affords adequate security, unit personnel find it difficult and slow to

operate. There is, therefore, a tendency to avoid the use of cipher with a

consequent possibility of overstrain of other safe means of communication or

the use of wireless in clear to a dangerous extent.

3. It

has, therefore, been decided to adopt a new Low Grade cipher, called LINEX,

details of which are given in appendices A to D, in place of Double

Transposition’.

So, to summarize the British cipher systems (Cysquare, enciphered three figure codebooks, codebooks enciphered with the SS Frame, double transposition) were not superior to the M-209, especially when one considers the following points:

1). Speed of encipherment/decipherment

2). The investment that would have to be made in creating,

printing and distributing codebooks and enciphering tables to field units.

3). The impact that their compromise would have had in

maintaining cryptosecurity.

7). M-209 vs Enigma:

Regarding the cryptologic strength of the M-209 machine

versus the plugboard Enigma, the expert on classical cipher systems George

Lasry (49) has stated:

‘One comment about

the security of the M-209. The claim that the Enigma is more secure than the M-

209 is disputable.

1) The

best modern ciphertext-only algorithm for Enigma (Ostward and Weierud, 2017)

requires no more than 30 letters. My new algorithm for M-209 requires at least

450 letters (Reeds, Morris, and Ritchie needed 1500). So the M-209 is much

better protected against ciphertext-only attacks.

2) The

Turing Bombe – the best known-plaintext attack against the Enigma needed no

more than 15-20 known plaintext letters. The best known-plaintext attacks

against the M-209 require at least 50 known plaintext letters.

3) The

Unicity Distance for Enigma is about 28, it is 50 for the M-209.

4) The

only aspect in which Enigma is more secure than M-209 is about messages in

depth (same key). To break Enigma, you needed a few tens of messages in depth.

For M-209, two messages in depth are enough. But with good key management

discipline, this weakness can be addressed.

Bottom

line – if no two messages are sent in depth (full, or partial depth), then the

M-209 is much more secure than Enigma’.

8). Rejection of the M-209 leads to development of the

Combined Cipher Machine - CCM

In 1942 there were discussions between US and British

officials regarding the adoption of a cipher system for combined military

operations. The Americans proposed that the M-138 strip cipher and the

Converter M-209 be used for this purpose but neither system satisfied the

British (50).

The British considered their Typex cipher machine secure enough for these communications but during the war production remained at relatively low levels. For this reason, a cipher attachment was developed that could be installed on to the US SIGABA and the British Typex Mk II cipher machines and it was produced by the US in large numbers. This was the Combined Cipher Machine - CCM and it was a 5-rotor non reciprocal system, issued with 10 rotors. The CCM was used extensively by the Anglo-Americans in the period 1943-45.

9). Slow,

cumbersome and inaccurate?

The US Army’s M-209 cipher machine was a powerful

encryption system, even if it could sometimes be solved through mistakes in

encipherment. Compared to hand ciphers it was faster and easier to use (once it

had been set up), however it seems that contrary to regulations the US troops

did not always use this system in the field since it still took too long to

encipher their messages (a problem solved postwar through the use of enciphered

speech devices):

‘Report of interview with S/Sgt, Communications Section 79

Inf Div, 7th Army’. (dated March 1945) (51):

"The US Army code machine #209 was found to be

something that hampered operations. It would take at least half hour to get a

message through from the message center by use of this code machine and as a

result the codes of particular importance or speed, for instance mortar

messages, were sent in the clear."

Also, from the ‘Immediate report No. 126 (Combat Observations)’ - dated 6 May 1945 (52): ‘Information on the tactical situation is radioed or telephoned from the regiments to corps at hourly or more frequent intervals. Each officer observer averages about 30 messages per day.………………The M-209 converter proved too slow, cumbersome and inaccurate for transmission of those reports and was replaced by a simple prearranged message code with excellent results’.

The British also noted the difficulty in setting up and operating the machine when evaluating its use as a NATO third level (tactical) cipher system in 1952 (53):

‘2. The U.K. Services nave now completed their trials

and report as follows:

a. The setting up of the machine is complicated

and lengthy. It takes from 20 to 35 minutes according to conditions of light,

temperature, etc., and might be well be nigh impossible under the most adverse

conditions to found on active service.

b. Operation of the machine is slow and tends

to become slower owing to eye-strain due to the scrambling of the alphabet on

the setting wheel.

c. Grit, dirt and damp may impair the function

of the machine under active service conditions.

3. On practical grounds the U.K. Services are

not prepared to use this machine for intra or combined purposes.

4. The UK Services agree however that the

machine may fulfill a useful role at the third level in other NATO nations who

may lack better equipment and that its use by those Nations at that level

should be authorized provided the restrictions in the following paragraphs are

enforced……………………………………’

10). German cryptanalytic reports on the Hagelin C-38/M-209

The following Hagelin C-38 reports were among the records

of Inspectorate 7/VI recovered in 1947 by the US authorities from a camp in

Glasenbach, Austria (54).

BC 38

Losung

der BC 38 aus einem langen Chi-text (Berichtfragment) 1944.

2.

Aktenvermerk ueber Erkennen von Phasengleichheit bei alphabetischen

Spaltenverfahren. 8 Sept. 1944.

3.

Aktenvermerk ueber das Erkennen der Phasereeleichheit bei alphabetischen

Spaltenverfahren. 30 September 1944.

Untersuchungsergebnisse

betreffend Schluesselgleichheit an franzoesisehen mit BC-38 verschluesseltem

Spruchmaterial (von Ref. B2)

Aktenvermerk

ueber einige Eigenschaften von Haeufigkeits-verteilungen der BC-38. 6 Sept.

1944.

Erklaerung der Z-Leiste.

Plan

fuer die Bearbeitung der amerikanischen und schwedischen Maschine BC 38.

19.8.44.

Aktenvermerk

ueber Erkennen der Phasengleichheit bei alphabetischen spaltenverfahren. 8 Juli

1944,

Aktenvermerk.

1. Theoretische Chi-verteilungen der BC-38 bei verschiedenen Klarhaeufigkeiteno

2. Theoretische Chi-haeufigkeitsverteilungen der C-36.

10

Chi-Haeufigkeitsverteilungen der BC 38 mit USA-klarhaeufigkeiten.

Bericht

ueber die analytischen Untersuchungen, die zur Bestimmung der amerikanischen

Schluesselmaschine M-209 fuehrten. 1 Juli 1944.

Aktennotiz

zur schwedischen BC-38. 13 Juni 1944.

Bericht

ueber eine Methode zur Vorausscheidung der Konstanten C26 und C25 bei der

absoluten Einstellung (AM 1) 27.6.44.

Erstellung

des Tagesschluessels der amerikanischen Maschine M-209 bei Vorliegen von 2

Spruechen mit gleichen Kenngruppen 27 Januar 1944.

Aktennotiz

zur Maschine C36. 21.1.44.

Bericht

OKM/SKL/Chef MND IIIe ueber Loesungsmoeglichkeiten der

Hagelin-Schluesselmaschine mit z. T. doppelten Reitern (Type BC 38). 18.11.43.

Sicherheit

der Chiffriermaschine BC 38. 16 Okt. 1943.

Bericht.

Ausl. Chiffrierwesen. 15 Maerz 1943.

Technische

Erlaeuterung zur maschinellen Bearbeitung von AM 1 Kompromisstextloesungen auf

der Texttiefe.

Betrug