Military and intelligence history mostly dealing with World War II.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

More Seabourne reports available

Randy Rezabek

of TICOM archive has uploaded more Seabourne

reports. The new ones cover cryptanalysis in the German AF, the OKW Radio

Defence Corps and the Signal intelligence Service of the Luftwaffe.

Monday, November 25, 2013

The German intercept station in Sofia, Bulgaria

The German

High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi intercepted radio traffic from various

stations both in Germany and abroad.

Stations in

neutral countries operated covertly, so as not to attract the attention of the

Allies.

One such

station was based in Sofia, Bulgaria. During WWII Bulgaria followed a pro-Axis

policy and declared war on Britain and the United States but did not take part in the fighting.

According to

Wilhelm Flicke, who worked for OKW/Chi, an intercept station was set up in

Sofia, Bulgaria in January 1940. The station was housed in the former residence

of the Communist official Stoitscheff who had fled the country.

Officially it

was designated ‘Seismographic and weather reporting station’ but the local

authorities knew its true function and cooperated with the Germans. The cover

name of the station was ‘Bohrer’, it had about 25-30 men and head of the

station was 1st lieutenant Grotz. Emphasis was given on the

interception of radio traffic from Turkey and Malta, as well as stations from

Egypt, Sweden, Switzerland and the US Armed forces in the Mediterranean.

The station

had a direct teleprinter connection with OKW/Chi and in addition there was a

courier plane between Sofia and Berlin.

Even though

Bulgarian officials helped in setting up the station this does not mean that

the Germans held back from attacking their codes. According to Flicke copies of

the Bulgarian codebooks were acquired by the Abwehr (military intelligence)

station in Sofia.

As the German

position in the Balkans began to unravel in 1944 the Sofia station was closed

down. This operation did not run smoothly. The equipment was loaded into two

freight cars and the personnel sold their unwanted items. With the money earned

they bought 80.000 cigarettes that they expected would be valuable back home. However

this ‘treasure’ was lost when the railway car was attacked by partisans and the

ammunition stored together with the cigarettes burned up.

Moral of the

story, never store tobacco and ammunition together, especially if you’re

travelling through the Balkans!

Update

I have

uploaded TICOM report DF-116-K ‘The

German intercept station in Sofia’ - 1948, written by Wilhelm Flicke.

Available

from my Scribd and Google docs accounts.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

British report on German armor piercing projectiles

The very

interesting report ADM

213/951 ‘German steel armour piercing projectiles and theory of penetration’

is available from World of Tanks forum user Daigensui.

From page 19

onwards there is a review of the German method of staging and conducting tank

round penetration trials. Source of the information was

‘The writer was fortunate in tracing

Oberbaurat HENNING TELTZ of Wa Pruef 1 (1X). This man was in charge of the

firing of all trials of A.P. Shell against armour plate, masonry, concrete and

soil and was responsible to Oberst Plas. He joined the H.W.A. in July 1933 and

thus had considerable experience. He had been living under an assumed name and

informed the author that he was the first allied officer who had interviewed

him. He was cooperative and appeared to be most efficient and it is thought

that the information given by him is complete and trustworthy.’Sunday, November 17, 2013

The unfortunate Henry W. Antheil and the State Departments strip cipher

During WWII

the high level cryptosystem used by the US State Department was the M-138-A

strip cipher. Unfortunately for the Allies this system was regularly solved

by the codebreakers of several Axis nations.

However there is one thing about this affair that still bugs me. The German solution of the strip system was facilitated by the material they received from their Japanese allies.

However there is one thing about this affair that still bugs me. The German solution of the strip system was facilitated by the material they received from their Japanese allies.

Agents of the

Japanese Military Police were able to enter the US consulate in Kobe in late

1937 and they copied the 0-1 ‘circular’ set of alphabet strips. This was used

for communications between embassies and for messages from Washington to all

embassies. This material was shared with the Germans in 1941.

However this

material was not the only set of strips that the Germans were able to acquire

covertly. Dr Wolfgang

Franz, who was responsible for the strip solution at the German High

Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, said in his report TICOM DF-176,

p6:

‘Especially laborious and difficult

work was connected with an American system which, judging by all indications

was of great importance. This was the strip cipher system of the American

diplomatic service which was subsequently solved in part. After I had been

working on it for a long time and was beginning to get some insight into the

system, the work was greatly furthered by some captured material. This was

given to me with no word as to its provenance.

From inscriptions and notes, however, one could infer that these were Japanese photographs. These were the basic

material of the so-called ‘intercommunication strip cipher system 0-1’ and

three further sets for special circuits between the Department and Reval, Tallinn and Helsinki (?)

with designations of the type 19-1 or something similar. With these, several

older messages could be read and the door was opened for further study of the

system.’

According to David

Kahn in ’Finland's Codebreaking in World War II’ in ‘In the Name of

Intelligence: Essays in Honor of Walter Pforzheimer’:

‘The Finns got their break into the strip

system when the German military espionage agency, the Abwehr, whose chief,

Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, was a friend of Hallamaa, gave them photocopies of

instructions for the strip cipher and of the strips for Washington's

communications with the posts at Riga

(which had been closed since June 1940) and Helsinki, as well as the 0-1 set.’

How did the

Germans get hold of the strips for Riga, Tallinn and Helsinki? From what I’ve

read the Japanese were the source for the 0-1 set not the rest.

The strips

from the embassies of the Baltic countries could have a connection with a

Finnish civilian plane shot down by the Soviets in 1940.

The Kaleva was a Finnish

civilian airliner that was shot down by Soviet planes on June 14, 1940, while

en route from Tallinn to Helsinki.

Onboard was a

US diplomatic courier, mr Henry W. Antheil, Jr

who was apparently carrying diplomatic pouches from the U.S. legations in Tallinn and Riga. According to the wikipedia page the plane crashed at sea and

the first on the scene were three Estonian fishing boats. Then a Soviet

submarine reached the location and recovered all the material from the

Estonians. This amounted to:

‘about 100 kg of diplomatic mail, and

valuables and currencies including: 1) 2 golden medals, 2) 2000 Finnish

marks, 3) 10.000 Romanian leus, 4)13.500 French francs, 5)

100 Yugoslav dinars, 6) 90 Italian liras, 7) 75 US dollars, 8)

521 Soviet rubles, 9) 10 Estonian kroons. All items were put on board

of patrol boat "Sneg" and sent to Kronstadt’

So the

question remains. If the alphabet strips from the Baltics were recovered from

the Kaleva plane, who got them and how did they end up in German hands?

Perhaps the

Estonian fishermen were able to search the diplomatic bags and they retrieved the

cipher material. Then when they got back to Estonia they could have given these

to the military authorities who in turn shared them with the Germans.

That’s one

theory.

Another one

could be that the Soviets after recovering the diplomatic bags searched them

thoroughly and recovered the alphabet strips. If that was the case then how

could the Germans have gotten hold of them?

Could there

be an exchange of secret material between the intelligence agencies of Nazi

Germany and the Soviet Union? In the period 1939-1941 they were officially ‘allies’….

Quite a

mystery!

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Estonian signals intelligence service

The signal

intelligence agencies of small nations usually receive little to no attention

from historians, mostly due to the lack of primary sources.

‘In 1939-1940 Section D units were stationed in Merivälja (7 km to the East from the city centre of Tallinn, probably next to the lighthouse of Viimsi, where the post of Naval Communications was situated, or somewhere in the area of nowadays Ranniku Road or Mõisa Road), Narva (probably at Olgino Mason 5 km to the North-East from city centre) and Tartu (probably in some of the units of the 2nd Division).’

‘When the Second Department closed down, it handed 51 items of literature over to the Red Army, including nine items concerning cryptology, a Russian-Estonian military dictionary and three Krypto ciphering clocks.’

The Estonian sigint agency

monitored Soviet traffic during the 1930’s and cooperated with the similar

departments of Germany and Finland. Unfortunately it is very difficult to find

information on their operations and successes.

Some

information is available from the very interesting article ‘Estonian Interwar Radio-Intelligence’ by Ivo

Juurvee (Baltic Defence Review No. 10 Volume 2/2003) , uploaded on site bdcol.ee

Some quotes:

‘The Estonian pre-war military

intelligence service - the Second Department of the General Staff - and

especially its radio-intelligence branch, Section D, have not been researched

much…’

‘The Wireless Station of the General Staff

in Tallinn intercepted the first radio messages of the Red Army during the War

of Independence (1918-1920).’

‘In contrast to other parts of the

Second Department, the personnel of Section D as of summer 1940 is precisely

known: it was 26 people . two officers, 23 NCOs and one private. Nobody had

been hired before 1936. This confirms the supposition that Section D was formed

in 1936-1937. The second officer, Olev Õun, was taken to service only in March

1938; so far Andres Kalmus had managed to supervise the section alone.

Radio-intelligence had gone through two major enlargements. The first of them

was at the beginning of 1937, when Section D had just started its work. The

second occurred in summer of 1939, when, according to President Konstantin

Päts. secret decree from July 10, .due to complex situation [in Europe] naval

radio intelligence has been reinforced.. With the order of the

Commander-in-Chief General Johan Laidoner from July 22, the radio crew of the

Second Department was enlarged .substantially..’

The top

codebreakers were Andres Kalmus and Olev Õun. Note that these

names also show up in some TICOM reports.

‘Captain Kalmus had followed military

radio courses abroad.’

‘Olev Õun was especially talented, who

was, in Hallamaa’s opinion, a phenomenal decipherer and had managed to break

the latest code of the Red Army during the Polish campaign in September 1939.’‘In 1939-1940 Section D units were stationed in Merivälja (7 km to the East from the city centre of Tallinn, probably next to the lighthouse of Viimsi, where the post of Naval Communications was situated, or somewhere in the area of nowadays Ranniku Road or Mõisa Road), Narva (probably at Olgino Mason 5 km to the North-East from city centre) and Tartu (probably in some of the units of the 2nd Division).’

‘When the Second Department closed down, it handed 51 items of literature over to the Red Army, including nine items concerning cryptology, a Russian-Estonian military dictionary and three Krypto ciphering clocks.’

Thursday, November 14, 2013

The British railways code

During WWII

all the participants had some success in intercepting and decoding the radio

traffic of enemy military units. Another type of traffic that proved to be very

important for military operations was the traffic of the railways organization.

By monitoring the movement of troops and supplies it was possible to identify

the buildup of troops at specific areas of the front and thus anticipate enemy

movements.

In December ’43 a list of the frequent abbreviations and aliases appearing on the ECr27 was prepared and sent to NAAS 5.

In December ’43 26 ‘keys’ and 2.304 messages were solved.

In January

’44 24 ‘keys’ and 1.871 messages were solved.

The solution

of this traffic in the period that the Anglo-Americans were preparing the

invasion of Western Europe may have given the Germans clues about the

concentration of forces in the Southern areas of the UK.

The

codebreakers of Bletchley Park attacked the traffic of the German Railways - Deutsche

Reichsbahn and started solving messages of the Eastern European network in

1941. Through this traffic they were able to monitor the movement of men and

supplies to the East.

The German

Army’s codebreakers were able to solve the code used by the NKVD railway troops

and thus they also got information on the movement of supplies and the

concentration of forces in specific areas of the front.

I’ve

mentioned in my piece on German

intelligence on operation Overlord that the Germans were able to solve the

code used by railway troops in Britain in late 1943.

According to

‘Delusions

of intelligence’, p46:

‘This same

Heer station had broken into the British railroads codes by late November 1943

and claimed a 98 percent success rate in reading the two thousand plus signals

produced by twenty-six keys in December 1943. Although not considered vital in

peacetime, such intelligence on Britain proved important by providing

information on the movement of troops and supplies.’

Obviously the solution of this traffic could have

compromised the security of operation ‘Overlord’. More details on this system are

available from the war diary of Inspectorate 7/VI and the reports of NAAS 5

(Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal Intelligence Evaluation

Center). This was the cryptanalytic centre of KONA 5 - Signals Regiment 5,

covering Western Europe.

The war diary of Inspectorate 7/VI shows that the radio

traffic of the railways was first investigated in late August 1943 and in

September a report was issued giving some information on these networks. There

were two main networks, The one from South London, covered the territory of the

Southern Railway (SR) and the Great Western Railway (GWR), the one in North

London covered the area of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMSR)

and the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER). Most of the traffic was from

the first network and a few of the station callsigns were identified (Ashford, Tunbridge

Wells, Chatham, London, Horsham). Some of the reports dealt with ‘coal

positions’, ‘crippled wagons’, the removal of ‘rubble’ and cement shipments.

Investigations continued in October and in November they

succeeded in solving the cipher used for station names. This was a paired Caesar,

meaning the well known Playfair

cipher. The square was changed each day and during the month 12 keys were

solved. The results were communicated to NAAS 5 so that they could take over

the solution of this traffic (called ECr27

in the reports).

In December ’43 a list of the frequent abbreviations and aliases appearing on the ECr27 was prepared and sent to NAAS 5.

In December ’43 26 ‘keys’ and 2.304 messages were solved.

However in

February ’44 the code was changed and from 16 February no such traffic was

intercepted.

Sources: Delusions of intelligence, E-Bericht

NAAS 5, Kriegstagebuch Inspectorate 7/VI

Monday, November 11, 2013

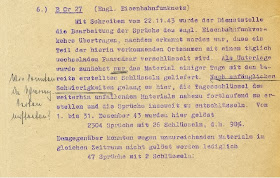

Solution of prewar Polish diplomatic code by OKW/Chi

In the field

of signals intelligence and codebreaking Poland, despite being a small state,

distinguished itself by being the first

country to solve messages enciphered with the German military’s Enigma machine.

However the Poles did not have similar successes in the field of crypto-security. Their diplomatic, intelligence and resistance movement codes were regularly read by the Germans prior and during WWII.

An interesting case is the solution of the main Polish diplomatic code by the codebreakers of the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, during the 1930’s.

Another serious mistake made by the Poles was that the substitution table for the month was not created randomly but instead had systematic features that helped the Germans in recreating them.

However the Poles did not have similar successes in the field of crypto-security. Their diplomatic, intelligence and resistance movement codes were regularly read by the Germans prior and during WWII.

An interesting case is the solution of the main Polish diplomatic code by the codebreakers of the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, during the 1930’s.

Details on

the Polish code are available from TICOM report DF-187G, pages 11-19.

This report was written by Wilhelm Fenner, head of the cryptanalysis department

of OKW/Chi.

According to

Fenner the Polish code used since the 1920’s was 4-figure. Through repetitions

in the code values the Germans deduced that this code was enciphered with a

simple substitution of the digits. Obviously this system offered limited

security. Simply by comparing each day’s most frequent code groups it was easy

to figure out the daily substitution.Another serious mistake made by the Poles was that the substitution table for the month was not created randomly but instead had systematic features that helped the Germans in recreating them.

Later on the

substitution system was replaced with a more secure additive system. Again

however the Poles made the mistake of taking half measures. The additive

sequences used to encipher the 4-figure code were too short, and they were used

for long period of time. This led to messages being enciphered with the same

sequences and these ‘depths’ could be exploited by OKW/Chi.

During the

war the Poles continued to use additive sequences but these were read by the

Germans. This however doesn’t mean that these systems could be exploited at

will by them. Instead it was necessary to intercept as much material as

possible and to use special cryptanalytic equipment.

Thursday, November 7, 2013

Operational research in Northwest Europe - No. 2 Operational Research Section

A very

interesting report is available from site dtic

online. This is the report Operational

research in Northwest Europe , the work of No. 2 Operational Research Section

21 Army Group.(originally

found through world of tanks forum user GhostUSN)

There are separate chapters for airpower, artillery, tanks and infantry weapons.

The No2

research section teams followed the Allied ground troops and estimated the

performance and effectiveness of Allied weapons and tactics by gathering data

from the battlefield.

There are separate chapters for airpower, artillery, tanks and infantry weapons.

Monday, November 4, 2013

New NSA documents

Interesting

documents have been published in the press these last few days.

Saturday, November 2, 2013

WWII Myths – German tank strength in the Battle of France 1940

In May-June

1940 Germany shocked the world by defeating the combined forces of France,

Britain, Holland and Belgium in the Battle of France.

At the time

no one expected that the French forces would be defeated in such a short

campaign. During the interwar period the French Army was thought to be the best

trained and equipped force in Europe. On the other hand Germany had only

started to rearm in the 1930’s.

The sudden

collapse of France led to a search for the reasons of this strange defeat. There

was no shortage of excuses. Every part of France’s defense strategy came under

attack, from the old Generals of WWI that tried to control the battle from the

rear to the funds wasted building the Maginot line.

General

Gamelin who commanded the French forces told Churchill that the defeat was due

to: ‘Inferiority of numbers, inferiority

of equipment, inferiority of method’.

Was that

true? Considering the role played by the German Panzer divisions in cutting off

the northern part of the front it is important to have a look at their

strength.

Did the

Germans have more tanks than the Franco-British Alliance?

According to Panzertruppen

vol1, p120-121 the German Panzer divisions used in the Battle of France had

the following strength on May 10 1940:

Div

|

Regt

|

Pz I

|

Pz II

|

Pz III

|

Pz IV

|

Pz 35

|

Pz 38

|

Pz Bef

|

Sum

|

1 Pz Div

|

1,2

|

52

|

98

|

58

|

40

|

8

|

256

|

||

2 Pz Div

|

3,4

|

45

|

115

|

58

|

32

|

16

|

266

|

||

3 Pz Div

|

5,6

|

117

|

129

|

42

|

26

|

27

|

341

|

||

4 Pz Div

|

35,36

|

135

|

105

|

40

|

24

|

10

|

314

|

||

5 Pz Div

|

31,15

|

97

|

120

|

52

|

32

|

26

|

327

|

||

6 Pz Div

|

11

|

60

|

31

|

118

|

14

|

223

|

|||

7 Pz Div

|

25

|

34

|

68

|

24

|

91

|

8

|

225

|

||

8 Pz Div

|

10

|

58

|

23

|

116

|

15

|

212

|

|||

9 Pz Div

|

33

|

30

|

54

|

41

|

16

|

12

|

153

|

||

10 Pz Div

|

7,8

|

44

|

113

|

58

|

32

|

18

|

265

|

||

Total

|

554

|

920

|

349

|

280

|

118

|

207

|

154

|

2,582

|

The same

source gives the following losses at the end of the battle in page 141:

Pz I

|

Pz II

|

Pz III

|

Pz IV

|

Pz 35

|

Pz 38

|

Pz Bef

|

Sum

|

|

May

|

142

|

194

|

110

|

77

|

45

|

43

|

38

|

649

|

June

|

40

|

46

|

25

|

20

|

17

|

11

|

31

|

190

|

Total

|

182

|

240

|

135

|

97

|

62

|

54

|

69

|

839

|

How did the

German tank strength compare with the Allies? According to The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in

the West, p37-38 the French Army had in the Northeastern Front 3.254

tanks, the British Expeditionary Corps had 310 plus 330 in transit from the UK,

the Dutch Army had 40 armored vehicles and the Belgian Army roughly 270. Total

for the Allies came to 4.204.

So in the field

of tanks the Germans were definitely outnumbered. If we look at tank types it’s

easy to see that they were also outgunned. Their main vehicles were the Panzer I and Panzer II. The first had only

two machineguns and the second a 20mm gun. Against Allied tanks equipped with

guns of 37mm caliber and over they were cannon fodder.

The German victory

was not due to a numerical or qualitative superiority in armored vehicles. Instead

it had to do with the way they used their armored forces, grouping them

together, supporting them with ample airpower and providing them with dedicated

infantry, anti-tank, artillery and communication units.